Zombies, Cannibals and Werewolves | History Today - 6 minutes read

Over the centuries, claims of cannibalism have been used repeatedly to justify slavery and imperialism. Indigenous Americans and enslaved Africans, it was said, were uncivilised and un-Christian people, whose savagery could be curbed only by European control.

After the Atlantic slave trade came to an end, these ideas gained in strength. In the late 19th century, as a new generation of imperialists began to push for colonial renovation, they revived older arguments about savagery and civilisation to make their case.

A key point of reference was Haiti, whose revolutionary struggle against the French had led in 1804 to the creation of the world’s first black republic. Haiti’s very existence was a challenge to those who believed that non-white people were incapable of self-government. However, a combination of political crises, foreign exploitation and debt had plunged the nation into trouble. European imperialists argued that Haiti’s problems were the fault of its people alone. They were particularly contemptuous of Haitian Vodou (or ‘voodoo’), a local religion that blended Caribbean and African folk traditions with Christianity, which they believed had corrupted the people and led them back into barbarism.

Spencer St John was a British diplomat who had been posted to Haiti. His book, Hayti; or The Black Republic (1884), was probably the most globally influential text written about that island in the 19th century. It left a pernicious legacy. Using little more than rumours spread by white planters and European expatriates, he offered up a host of negative stereotypes about Haiti’s people, government, culture and religion, and claimed that Vodou ceremonies commonly involved child sacrifices and cannibalism. He offered his readers salacious stories of cannibalism, of people being buried alive, children murdered by the dozen and even tales of packages of salted human flesh wrapped in leaves for storage. ‘Every foreigner’, St John wrote, ‘knows that cannibalism exists.’

St John’s allegations spread widely. From the perspective of British imperialists, the problems Haiti faced would be repeated in the British West Indies if local people were given full rights and local cultures allowed to flourish. In 1890, for instance, the attorney general of Barbados told a visiting journalist that ‘in spite of centuries of Christian rule devil worship was a fact in most of the islands’. Only European control would keep it suppressed. The choice in the West Indies, wrote the Oxford historian James Anthony Froude, was ‘either an English administration pure and simple like the East Indian, or a falling eventually into a state like that of Hayti, where they eat the babies, and no white man can own a yard of land’.

These arguments also helped to justify the US invasion of Haiti, which began in 1915. One potted newspaper history published a few months later described the country as the ‘grave of 50,000 whites’, a fertile land that had become ‘the burying ground of a once prosperous white race, destroyed by a Frankenstein [’s monster]’ of its own creation.

During the 20-year occupation that followed, the US sought to clamp down on Vodou using laws against poisoning and les sortileges (spells), as well as more brutal methods. Marines raided Vodou ceremonies, arresting and assaulting participants and destroying ritual objects.

In part this was because the occupiers correctly understood that local religious leaders could lead resistance against the occupation, just as they had against France. However, discussions about human sacrifice and cannibalism were also a useful diversion when allegations of torture and violence by marines on the island began to be raised by critics at home. In response to claims of the ‘indiscriminate killing’ of Haitian rebels, officials told journalists that captured marines had been subjected to ‘the most barbarous indignities’ including being ‘offered as sacrifices to the Voodoo gods’, their bodies ‘disembowelled and the viscera hung on trees’. General Lejeune of the US Marine Corps alleged that Haitian rebel forces had killed and eaten the ‘vital organs’ of American marines in order to absorb their courage. Shooting captured rebels, it was implied, was an entirely proportionate response.

Many Americans believed that ‘Christianising’ the island was a key reason for the occupation in the first place. As a result, it was argued that US control had seen Vodou rituals fall into decline in the 1920s – that, in the words of one journalist, the ‘marines have silenced many of the voodoo drums’. In practice, however, the long occupation only amplified the ghoulish image of Vodou.

This led to an explosion of interest in Haitian religion in the US, but often a distorted version that blended fragments of inherited French folklore – such as the loup garou, or werewolf – and Haitian creole elements such as the zombi with the lurid stories of cannibalism. The small number of anthropologists and journalists who sought to understand Haiti’s complex religious landscape more soberly could do little to counter this tidal wave of misinformation.

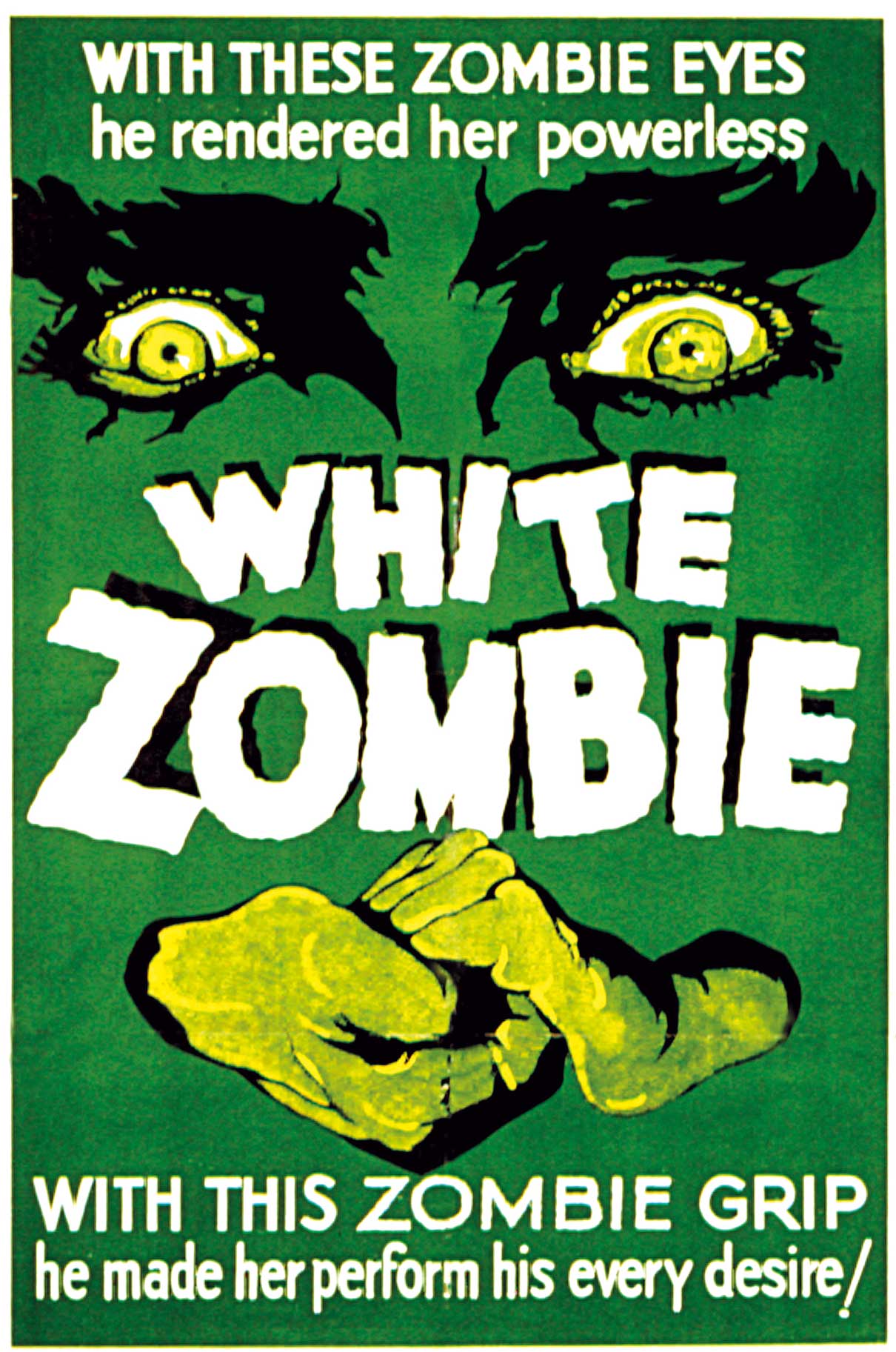

Since 1932, when Victor Halperin directed the first ever zombie film, White Zombie, zombies, cannibals and werewolves have become staples of the dark underbelly of cinematic imagination, often retaining their racialised associations not very far beneath the surface. Probably the most famous example is Live and Let Die (1973), in which James Bond travelled from Harlem to New Orleans then Haiti to hunt down a drug-dealing Caribbean dictator who used a Vodou priest to terrorise the local population and force them to work on his opium fields. Ironically, the use of religion to control the local population and make them obedient plantation workers is a better description of the historical role of established Christianity in the Caribbean than of Vodou.

Nor did these ideas stay in films. Similar claims about the savagery of Haitian culture emerged during the second US invasion of the island in 1994. And, following the Haitian earthquake of 2010, the US Baptist minister Pat Robertson claimed the disaster was punishment from God because Haitians had made a ‘pact with the devil’ during their struggle for independence. Even though figures such as Spencer St John are long forgotten, their myths and mistakes still survive.

Alex Goodall is a senior lecturer in International History at UCL.

Source: History Today Feed