Behind Closed Doors | History Today - 4 minutes read

The marriage of William Morris, designer-businessman, and Jane Burden, stableman’s uneducated daughter, has long been the subject of curiosity. Not so much for its cross-class features, which were relatively common in the Victorian age, but for its sequel. Eight years after the wedding and the birth of two children, Jane began an affair with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William’s friend and business partner – with the agreement, if not approval, of her husband.

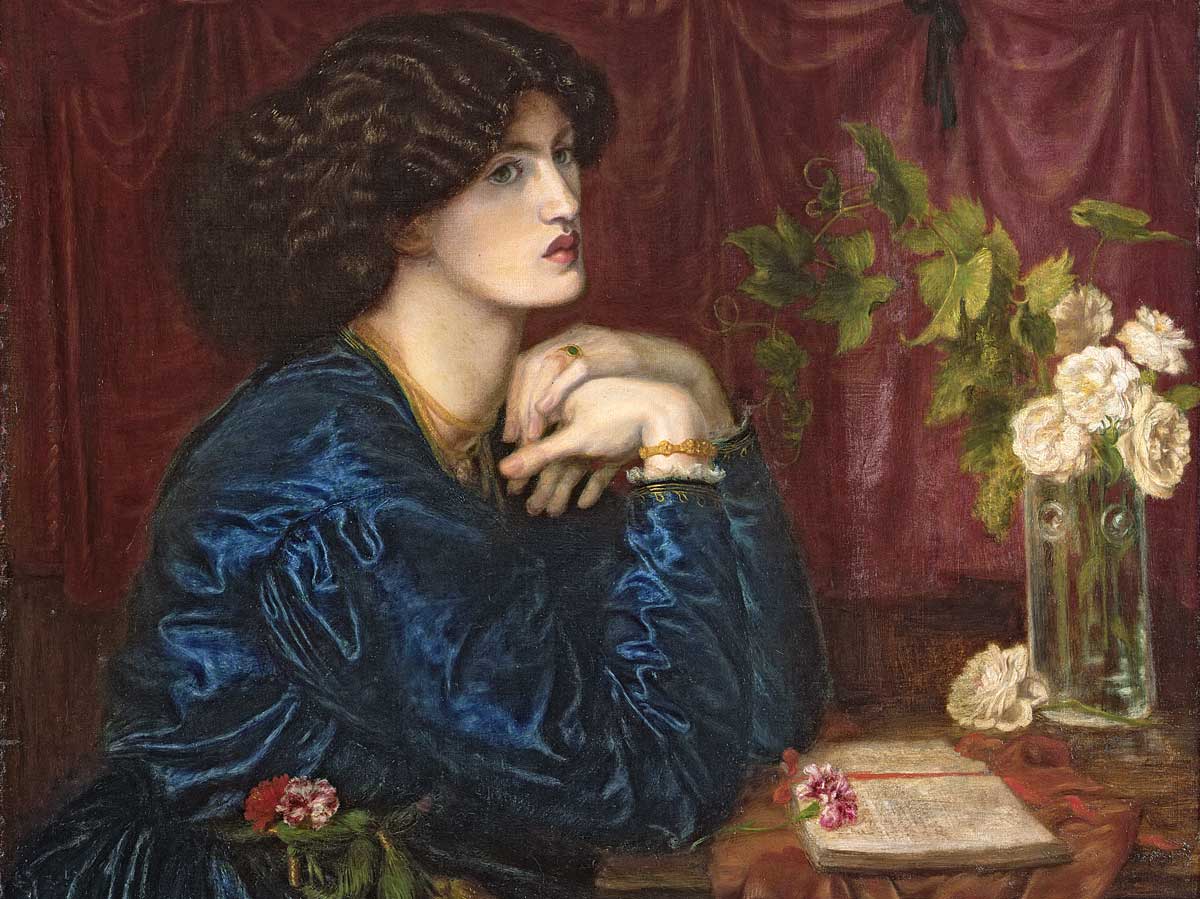

Why and how did this happen? Those known to the couple as well as posterity have struggled to explain it. The standard view is that ‘Janey the Beautiful’ was simply overcome by the passionate, determined Rossetti. But clearly it was Jane’s decision to spend summers with Rossetti and winters in London with her husband and daughters, Jenny and May. And to ensure this was deftly accomplished.

Suzanne Fagence Cooper has previously chronicled the comparably adept manner in which Effie Gray extricated herself from an unhappy, unconsummated marriage to John Ruskin in order to become the wife and artistic partner of John Millais. In How We Might Live, she traces the Morrises’ shared and separate lives with the same clarity and judicious assessment.

After the chance meeting in Oxford, when the Pre-Raphaelites were painting a series of murals in the library of the Oxford Union debating society, young Jane and William began married life by designing and decorating their own newly built Red House at Bexleyheath in Kent, which remains remarkably untouched – although now set amid suburbs, not orchards. Jane came from the servant ranks; henceforth she managed the household. She learnt to play music and read French and Italian and taught her daughters in turn. The couple were both involved in the firm that became Morris & Co., decorating church and domestic interiors (yes, the wallpapers and fabrics). Jane, her sister Bessie and other women stitched richly patterned altarcloths; soon Jane managed the embroidery commissions. Convivial business meetings were held in the Morrises’ next home in central London and the family holidayed with the Burne-Joneses and Faulkners.

William Morris is everyone’s hero. Jane has a comparably terrible reputation as a silent, sulky, faithless wife. With sympathetic warmth, Cooper leads us through the couple’s experiences. She imagines them in various locations but does not seek to invent their thoughts. Some known details are omitted – Jane’s unfulfilled wish for a son, her clandestine correspondence with Rossetti, William’s extravagant spending. But there is so much to include. Notably the evolution of William’s aesthetic taste from quaint medieval to proto-modern plainness, plus the analytical account of the tiny ornamented booklets that Jane created – when and for whom were they designed? No letters from Jane to William or his family survive, so we don’t know what she called him at home. In the group, he was ‘Topsy’ or ‘Top’; outside it was always ‘Mr Morris’.

In its focus on personal lives, biography like this is not ‘history from below’ so much as what Phyllis Rose called ‘higher gossip’. It draws readers along engaging narratives to which we can relate. William, whose achievements are so various in poetry, design, manufacturing, politics, calligraphy, translation and publishing, also wrote of his ‘disappointments and tacenda’ – things best left unsaid. These include his failure as a lover and, most painfully, the awfulness of Jenny’s epilepsy, which struck when she was 15. Jane grieved acutely and had her own ‘unspoken’ list, including her childhood and the destroyed or hidden love letters from Rossetti. For the months they spent at Kelmscott Manor near Lechlade, we must go to his poems.

The Manor has reopened this year after a refurbishment. Thanks to the whole Morris family, who loved the house and walled garden excessively, it preserves its enchanted, out-of-time atmosphere. One strength of Cooper’s storytelling is its attention to how Jane and William created each of their homes, with comfort and fine objects but without superfluity. If we can believe it, there was nothing that was not either beautiful or useful. Their relationship, too, was a shared construction, mortared with tact. When Rossetti’s conflicted shame in ‘stealing’ his friend’s wife drove him to a paranoid breakdown, William allowed him to convalesce at Kelmscott until Jane acknowledged she could not mend his mind. Nothing records William reproaching Jane or gloating over this outcome. All observers noted the quiet affection between the couple.

There have been many books about William Morris and will be many more, but How We Might Live paints a genial picture of entwined and, overall, happy lives.

At Home with Jane and William Morris

Suzanne Fagence Cooper

Quercus 320pp £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Jan Marsh is the former president of the William Morris Society.

Source: History Today Feed