The Rise and Fall of Mein Kampf - 7 minutes read

Books hold a special power. We read, we buy or borrow, we support public libraries and campaign to keep them open. We lament when libraries are closed and especially when they are damaged in times of conflict. Underpinning these concerns is an assumption, seldom tested, that books are invariably a force for good: a civilising influence to be cherished and preserved.

But what about when they are not? Books are not just victims of war, they are also protagonists and provide, through their contribution to scientific discovery, intelligence and propaganda, the munitions. They incubate the ideologies that set nations against each other; they perpetuate the stereotypes that lead to atrocities and genocide. Books are never above the fray; they reflect the human frailties and evil intent of those who go to war, even as reading provides a haven of peace in troubled times.

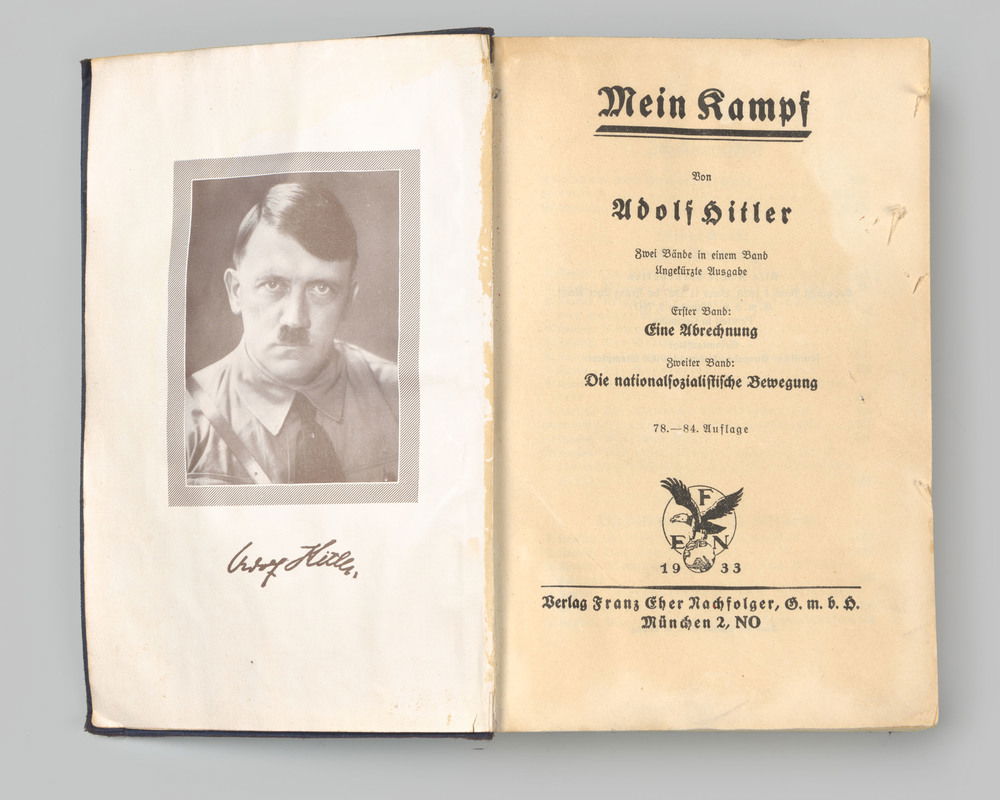

We can explore these paradoxes through the lens of one bestseller, Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Like its author, on its first publication in 1925 it looked destined for oblivion: the first part sold only 1,500 copies and, had its publisher not been one of Hitler’s most fervent supporters, the notorious second part, which contains much of the toxic racial theorising, would never have seen the light of day (it sold a mere 500 copies). But the nearer the Nazis came to power, the more sales increased. When, in 1933, the triumphant new regime moved to clear ‘decadent’ literature from German public libraries, Mein Kampf and other staples like Alfred Rosenberg’s incomprehensible Myth of the Twentieth Century took its place. New editions in a variety of formats made it accessible to all German citizens: it soon became a customary gift to newlyweds setting up their own homes. Army officers and schoolteachers were expected to have a firm knowledge of the text, to spread among their troops and schoolchildren. By the end of the war, thanks to forced sales to schools, public libraries and the prudential purchases by the population at large, nine million copies were in circulation in Germany.

If Mein Kampf was an obligatory presence in every German household, if not necessarily well thumbed, readers elsewhere were under no such compulsion. That it was, nevertheless, so widely published makes for an interesting story. English and American readers first had access to Mein Kampf only in 1933, when Hitler was an object of curiosity on the international scene, and then only in an abridged version. This was doubtless to make it more accessible, but it did have the effect of smoothing the rough edges and excising much of the more provocative material. President Roosevelt complained that ‘this translation is so expurgated as to give a wholly false view of what Hitler says’. Nevertheless, it sold more than 50,000 copies. France, too, had two rival editions, one so generously abridged as to give those on the French Right, despairing at their own government, a somewhat rosy view of Hitlerism.

It was only in 1938-39, as war was imminent, that readers in Britain and the United States were exposed to the unexpurgated Mein Kampf, in a new translation available in both book form and in 18 weekly instalments (priced at sixpence each). Although it seems to have found very few admirers, from a publishing point of view it was a runaway success, making The Bookseller bestseller charts. The publisher, Hutchinson, reprinted the book version six times between 1939 and 1943. They were careful to emphasise that the royalties would be passed on to the Red Cross, responsible for the book service for Prisoners of War.

Although the British government, like all combatants, introduced stricter censorship of the printed word from the beginning of the war, there was no attempt to inhibit access to Mein Kampf. On the contrary, public libraries were soon buying extra copies to cope with demand. In December 1939, the Kent County Library Service reported it had 52 copies in circulation, not quite the 135 copies of the runaway bestseller Gone with the Wind, but a remarkable number nevertheless. It says something for the insouciant sense of self that characterised the British in this period (and so annoyed their American allies) that rival ideologies were treated more as an interesting curiosity than a real threat. As the British army settled into barracks springing up around the English countryside, Mein Kampf was a recommended purchase for all camp libraries.

The sentiment seemed to be that the more people were exposed to Hitler’s ranting, the more convinced they would be of the evils of Nazi Germany. This seems indeed to have been the case. When Joan Strange, a member of the Peace League and a reluctant convert to the necessity of war, was sent a copy by a German friend, Sep Strasser, it got predictably short shrift. While Sep was confident it would make Joan an ardent National Socialist, Joan only needed to read a few pages of Mein Kampf in bed to know there was no chance of Sep’s prophecy coming true. Likewise, some British soldiers used Mein Kampf to while away the endless hours of captivity as prisoners of war. Sydney Litherland, the son of an architect, was well on the way to obtaining his architectural qualifications when called up in February 1940. He was captured in Crete and moved through several camps, in one of which all the prisoners were provided with copies of Mein Kampf in English. It did not impress:

I did persevere with it and read it from cover to cover, which gave me an insight into the rise of the Third Reich, in particular Hitler’s anti-Semitism and all the terrible consequences which followed ... Generally newspapers were not kept as they were too valuable as loo paper and this was also the fate of many of the copies of Mein Kampf, including mine.

In Germany, as the tide of war turned, so did the esteem for Hitler’s text. By 1944, the publishing industry was in turmoil, its headquarters in Leipzig largely destroyed and most bookshops closed for lack of staff and stock. As the Allied troops occupied the homeland, German families were not slow to dispose of compromising texts, and the Führer’s masterwork was not spared. A young female publishing executive trapped in Berlin at the end of the war recorded that Nazi literature could still be useful in the bombed out homes in which they sheltered.

The cold doesn’t want to go away. I sit hunched on the stool in front of our stove, which is barely kept burning with all sorts of Nazi literature. Assuming everyone is doing the same thing – and they are – Mein Kampf will go back to being a rare book, a collector’s item.

And so it proved. Even at book fairs, dealers remain reluctant to display a copy of Hitler’s text. In Germany, it was not until 2016 that Mein Kampf was published again, in an expensive and carefully annotated scholarly edition. But its initial success is proof, if that were needed, that books carry in them all the complexities of humanity. Books are a welcome source of inspiration and education; they provide comfort and relaxation. Yet in times of conflict their power to persuade shows a different face. Books are truly the seedbeds of ideology and the munitions of war, as committed to the cause as their readers.

Andrew Pettegree is Professor of History at the University of St Andrews and the author of The Book at War: Libraries and Readers in an Age of Conflict (Profile, 2023).

Source: History Today Feed