Empire in the Everyday | History Today - 6 minutes read

In 1919, the Korean gentleman farmer Yu Yŏnghŭi (1890-1960) wrote in his diary:

Fourth month, eighth day. Sunny. As yesterday. Yesterday morning I went to the township office. I got two sheets of white hybrid silkworm eggs and returned.

In 1925, Chŏng Kwanhae (1873-1949) recorded a similar, typical day in his life:

Second month, twelfth day. From noon it started to snow through to evening, until a person would sink to their calves … I went to meet Mr. Kim Hyŏngok on the road to Haegok [village] … I said, ‘I want to operate a mulberry seedling field but the seeds are hard to find.’ Kim said … ‘I have a catalogue. If you borrow it you can try [to order seeds] and see for yourself.’

At first glance mundane and everyday, these entries offer insight into the turbulent political and social changes that characterised the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Korean history. Following the opening of Korean ports to new forms of trade and diplomatic relations in 1876, a series of wars, rebellions and reform movements transformed Korean society in a few short decades. Annexation by Japan in 1910 compounded and complicated the tensions surrounding economic and social change, as colonial policies designed to favour the interests of the Japanese empire exacerbated divisions among the Korean population. Despite lasting just 35 years, legacies of colonial rule continue to inform politics in the two Koreas, emerging in debates over how to address questions of historical collaboration, income inequality, wartime trauma and forced labour.

Living outside the capital, Yu and Chŏng’s diaries offer a distinctly local, mundane perspective into life under colonial rule. Yu and Chŏng are largely unremarkable figures. Though both hailed from elite lineages and received sufficient education to maintain their diaries, neither was wealthy enough to escape the fear of debts or a bad harvest. Rather than discussion of colonial politics or social movements, their diaries instead recorded the weather, their relationships with neighbours, friends and family, and the routines of the agricultural calendar.

Nonetheless, the diaries of Yu and Chŏng are instructive precisely because of their focus on the day-to-day routines of their authors.

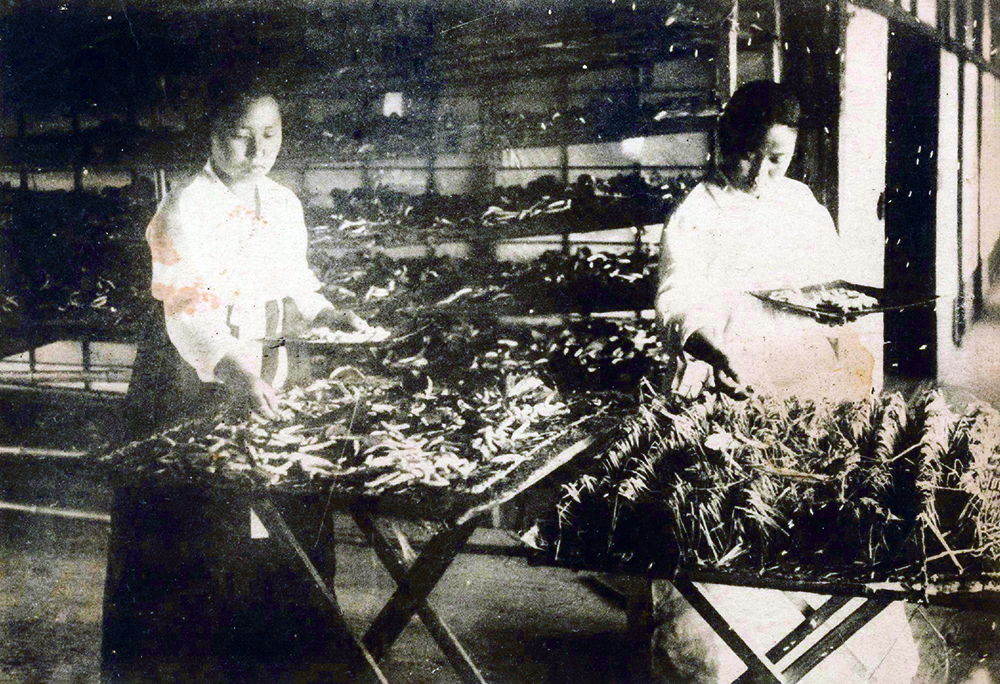

Of course, Yu and Chŏng’s lives were not untouched by the expansion of the Japanese empire. The colonial government introduced policies that influenced all aspects of life in Korea. As the main industry that supported over 70 per cent of the population throughout the colonial period, agriculture received particular attention from officials who sought to ‘improve’ existing practices and establish Korea as a profitable part of the Japanese empire. The silkworm eggs that Yu obtained from the township office are just one example. In earlier years, Yu had acquired silkworm eggs from an acquaintance in a neighbouring village after hearing about them from his friends. After colonial officials identified sericulture as a promising industry, however, local government offices were increasingly active in promoting it – importing new silkworm breeds, encouraging the sale of cocoons and linking farmers with agricultural technicians to oversee training and silk production. That, by 1919, Yu obtained silkworm eggs from the township office rather than his network of friends and acquaintances reveals the material expansion of the colonial state, with the township office blurring the lines between commerce and control. Although Yu often bristled in his diary at the imposition of government surveys and inspections, the township office gradually became an important part of his economic life. In later years, these connections would facilitate wartime mobilisation campaigns, but from 1919 the expansion of the state appeared less as a sudden shock of foreign rule than a slow, grumbling redirection of resources amid Yu’s existing economic activities.

As for Chŏng, the catalogue recommended by his friend would connect him to seed distributors in Tokyo – a commercial complement to the colonial government’s efforts to popularise and distribute new seed varieties. The mulberry seedlings that Chŏng planned to purchase were intimately connected to colonial attempts to expand the cultivation of silkworms and, by extension, the mulberry leaves that they consumed in large quantities.

Not unlike Yu’s foray into sericulture, Chŏng sought the mulberry seedlings of his own volition. Yet Chŏng’s desire to cultivate mulberry trees also speaks to the broader changes in the rural economy. Following riots over high rice prices in Japan, in the 1920s the colonial government introduced ambitious plans to increase the production and export of Korean rice in order to relieve prices for Japanese consumers. Colonial rice campaigns took the form of large-scale investment into irrigation facilities and the promotion of fertilisers and high-yielding seed varieties, increasing rural households’ sensitivity to market prices as they found themselves newly liable for water fees, fertiliser purchases and irrigation-related debts. Indeed, Chŏng explained his interest in mulberry cultivation as a direct consequence of the recent instability of rice agriculture: ‘These days life is getting harder, and farming alone is not enough. Besides the main industry, one must also have a side business.’ While farmers have always diversified through the cultivation of multiple crops, Chŏng’s decision reflects a bigger shift in the colonial rural economy, as government campaigns met the realities of an expanding, ever more precarious, market economy.

Of course, Yu and Chŏng’s diaries reveal just two experiences among many. But their diaries do more than detail the pervasive influence of colonial rule; they show how Yu and Chŏng understood changes to agriculture and the rural economy in the context of their daily lives. In this regard, the events that Yu and Chŏng recorded may be understood as part of a wider phenomenon. Yu engaged in sericulture, but this drew him into an uneasy dependence on local government offices. Chŏng’s interest in mulberry cultivation was driven as much by the precarity of rice agriculture as it was a desire to secure profits. For both, the impact of colonial rule was not always clear-cut but often appeared indirectly, through friends and acquaintances, changing prices in local markets, and interactions with township offices and village heads. The everyday encounters that Yu and Chŏng recorded in their diaries reveal the complicated dynamics of how the Japanese empire worked in practice.

Holly Stephens is Lecturer in Japanese and Korean Studies at the University of Edinburgh.

Source: History Today Feed