New Heights | History Today - 4 minutes read

The Sistine Chapel is the most important sacred space of the Roman Catholic Apostolic Church, where the College of Cardinals meets to elect each new pope. Its dimensions reflect those of Solomon’s lost temple in Jerusalem: the length three times the width; the height half the length. On its walls, squinches and ceiling are painted some of the greatest artworks of the Renaissance.

Antonio Forcellino’s excellent new book, elegantly translated by Lucinda Byatt, looks at why in 1477 Pope Sixtus IV commissioned a new chapel to be built in the Vatican (which now carries his name). Sixtus was acutely aware of the threat of invasion by the Ottoman sultan Mehmet II, whose conquering of Constantinople in 1453 had sent shock waves through all of Christendom. Having taken the capital of the second Rome, Mehmet II was entitled to call himself Caesar’s heir and lay claim to Rome’s cultural and spiritual legacy. As Forcellino explains, in commissioning artworks for his new chapel Sixtus sought to make it ‘a universal manifesto of Christian theology and papal legitimacy’.

In 1481, on the vaulted ceiling, Pier Matteo d’Amelia painted a deep blue sky decorated with golden stars, representing God’s firmament. For the walls Sixtus contracted a consortium of celebrated artists – Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Pietro Perugino and Cosimo Rosselli – to paint, in fresco, a series of large figurative scenes, depicting important stories from the Old and New Testament. These included Moses’ Journey into Egypt, Trials of Moses, Punishment of Korah, Baptism of Christ, Delivery of the Keys to Saint Peter and The Last Supper. Many buildings of ancient Rome were also depicted in the scenes.

As an art historian and restorer, Forcellino provides expert analysis of the artists’ working practices, their respective skills and weaknesses, and the precise technical requirements of successful fresco painting. The scenes are painted in true fresco – where paint is applied to still wet plaster and effectively becomes integral to it as it dries – a technique adopted with brilliant effect by Giotto in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (1303-05) and by Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence (1425-27). Forcellino describes the surprisingly effective way that the four artists worked side by side in the Sistine Chapel, resulting in homogeneity across the scenes. While all of the figures depicted demonstrated a sense of realism, the strictly prescribed stylistic conventions of the period dictated that they exhibit grace and ‘sweetness’ of expression. These are the attributes that Raphael later took to new heights in his Vatican apartment frescoes and in the cartoons he produced for the tapestries that subsequently hung in the Sistine Chapel.

Forcellino provides detailed analysis of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel artworks. These were commissioned by Sixtus IV’s nephew, Julius II, the so-called ‘Warrior Pope’, who was as happy leading his troops in battle as issuing missals from his papal throne. Julius won back territories for the Papal States and significantly replenished the Vatican’s coffers. He saw his pontificate ‘as the harbinger of a new era, the greatest ever’. As a learned patron of the arts, he was keen to commission revolutionary artworks, in which Michelangelo became his ‘irreplaceable political ally, an alter ego able to understand his passions and translate them into images’.

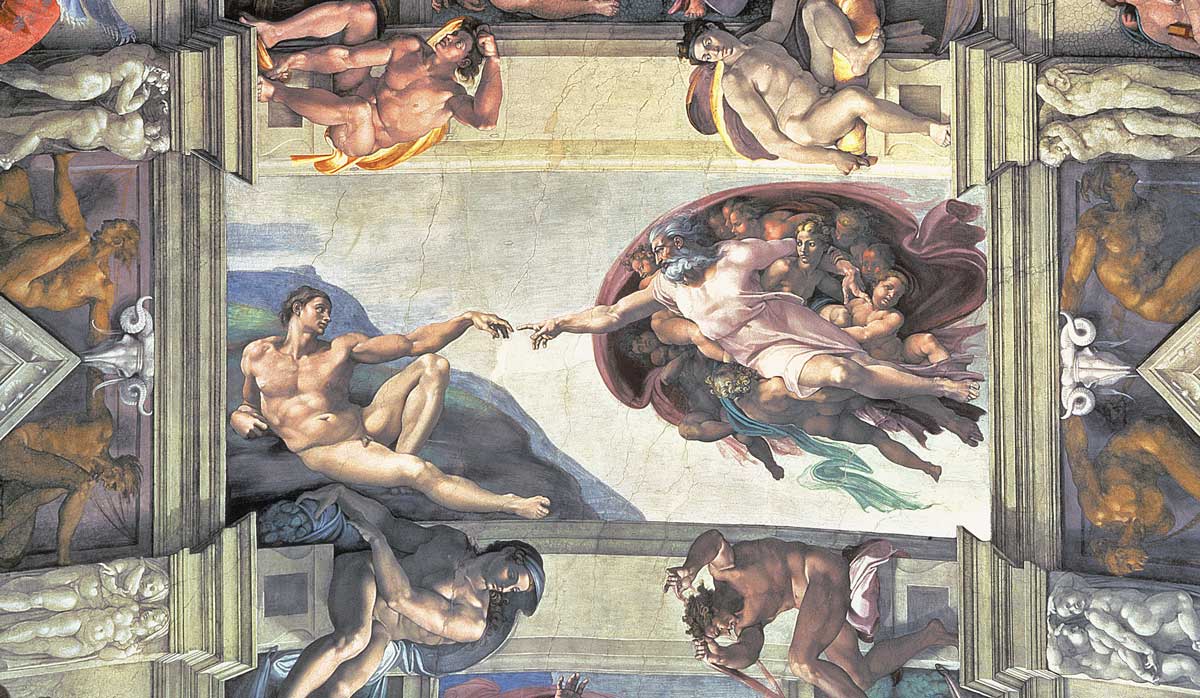

Although Michelangelo (then principally a sculptor) had little experience of fresco painting, he soon mastered the technique. In place of Pier Matteo d’Amelia’s starry sky, he painted a bold fictive architectural framework, within which he placed an array of brilliantly depicted, majestic and mainly nude human bodies and well-known biblical stories including The Flood, Separation of the Light and Darkness, Temptation and Paradise and what is, for many, the supreme artistic image of the Renaissance: The Creation of Adam.

Paul III was elected pope in 1534 following several existential threats to the Church, including the Lutheran Reformation and the 1527 Sack of Rome. It was in this context that a much older Michelangelo created his striking Last Judgement on the Sistine Chapel’s altar wall. Although immediately detested by many members of the curia, few could ignore its powerful message: this was a Christ, ‘as beautiful as Apollo, as powerful as Hercules’ who, in the moment of judgment, with his one raised arm, would fearlessly condemn the damned to the fire of hell in perpetuity and raise the sacred to eternal life. The Last Judgement captured the fears, hopes and sense of spiritual revival that the Roman Catholic Church was then experiencing. Forcellino’s book places the Sistine Chapel centre stage.

The Sistine Chapel: History of a Masterpiece

Antonio Forcellino, translated by Lucinda Byatt

Polity 250pp £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Philippa Joseph is a senior fellow at the Institute of Historical Research and a tutor in art history at Oxford University’s Department for Continuing Education.

Source: History Today Feed