Turkey and Europe’s Difficult History - 7 minutes read

‘Six decades of integration cannot be undone, even by a strongman like Erdoğan’

Dimitar Bechev, Author of Turkey Under Erdoğan: How a Country Turned from Democracy and the West (Yale University Press, 2022)

If Turkey and Europe were Facebook users their relationship would be permanently set on ‘It’s Complicated’. Starting with the late Ottoman Tanzimat reforms (1839-76), the model societies of Western Europe have provided a blueprint for Turkey’s modernisation. From Kemal Ataturk’s republic in the interwar period to the early years under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, when the desire to join the EU guided domestic politics, Turkey has sought to emulate advanced European countries in order to close the gap with what Kemalists called ‘contemporary civilisation’.

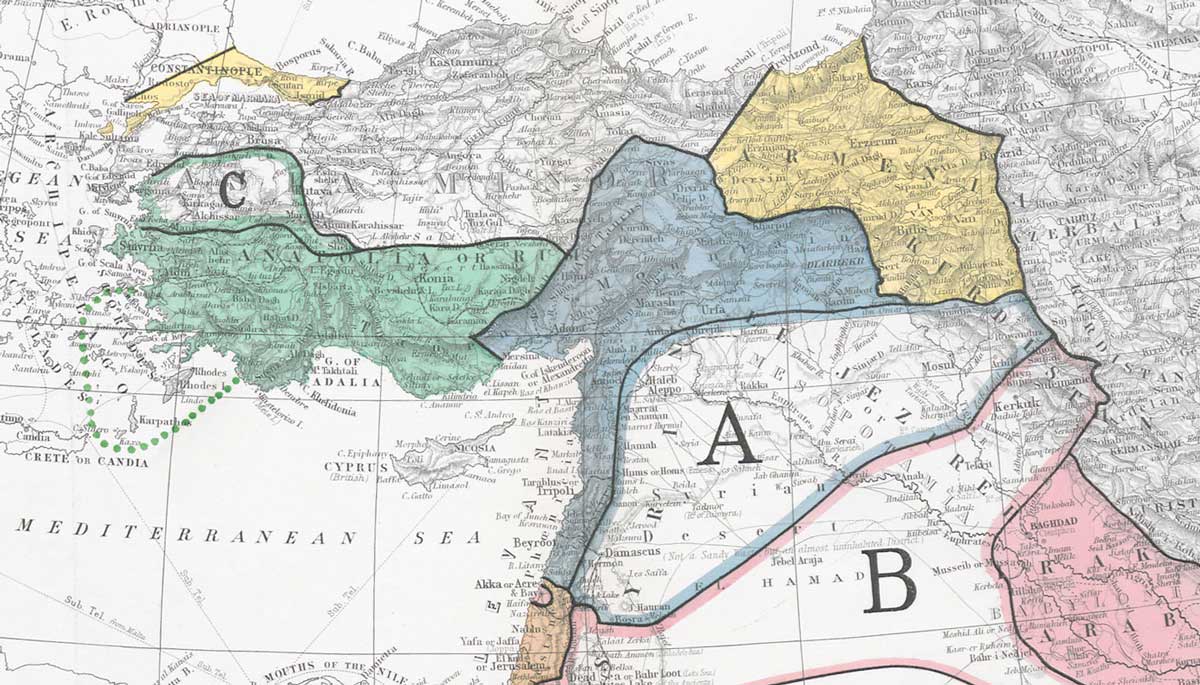

But that is not the whole story. Emerging from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire, modernisation was a means by which Turkey could uphold sovereignty and fend off predatory foreign states such as Mussolini’s Italy, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Suspicion of the outside world outlasted the Cold War. The so-called ‘Sèvres Syndrome’ – the belief that enemies are conspiring to undermine the Turkish state, named after the eponymous treaty which partitioned the Ottoman Empire in August 1920 – fed fears that Turkey’s partition could be repeated by Brussels’ push for minority rights, notably the Kurds.

Erdoğan, ever the populist, has co-opted nationalism. He governs in a coalition with the Nationalist Action Party and enjoys support from the ‘Eurasianist’ faction ensconced in the military, which has been rooting for an alliance with Russia and China since the early 2000s. Defying the US has become an article of faith. Europe is accused of keeping Turkey at arm’s length, unwilling to welcome a large, Islamic country into its midst. That is why many opinion makers cheer for Russia in Ukraine.

Meanwhile, Erdoğan periodically picks fights with European governments, which we can expect to see more of as elections in June 2023 approach. Yet trade and investment ties are dense. Millions of Turks live in Western Europe. On many issues, the EU is a partner. Six decades of integration into Europe’s marketplace and its political institutions cannot be undone, even by a strongman like Erdoğan.

‘An intermingling of facts and myths accompany the memory of the events of the last two centuries’

Çiğdem Oğuz, Author of Moral Crisis in the Ottoman Empire: Society, Politics, and Gender During WWI (I.B. Tauris, 2022)

Successive military defeats from the late 17th century onwards paved the way for admiration of the ‘European way’ within the Ottoman Empire. For a long time this approval was limited to Europe’s military and technical superiority and led to the reorganisation of the Ottoman army. Eventually, however, it was understood that the Ottomans had also lost their political superiority to Europe, a truth made clear by the Empire’s inability to stop Russian aggression from targeting its territories.

Reform was needed in order to save the state from downfall and the age of the Tanzimat (literally ‘Reorganisation’) followed. Yet while reforms concerning the military and politics were embraced by the Ottoman authorities, their cultural impact provoked a mixed reaction in society. The widespread sentiment of the late Ottoman era was summarised thus: ‘We will adopt the technology of Europe, but not their morality.’ The dangers of European cultural penetration and its impact on Turkey’s Islamic identity have caused heated debates that continue today.

Though the Ottoman Empire is gone, its legacy within contemporary Turkish politics, and especially with regard to the country’s relationship with Europe, should not be underestimated. Under Erdoğan an intermingling of facts and myths accompany the memory of the watershed events of the last two centuries, feeding an anti-Western propaganda that has served the current president well. Europe is often blamed for all of Turkey’s domestic and international problems. This is particularly true at times of political tension between Turkey and the European Union. The narrative here is that since Ottoman times Europe has made a continuous attempt to divide and destroy Turkey. This attack had a different name in the 19th century – then it was called the ‘Eastern Question’, during which the Ottoman Empire became the original ‘sick man of Europe’. Clearly, the relationship between Turkey and Europe is more nuanced than such a narrative allows, but populism thrives on historical grievances and they have proven most useful in consolidating pro-Islamic and nationalist public opinion.

‘The dominant paradigm in Turkish nationalism is that western countries chose to colonise, plunder and cheat their way to the top’

Selim Koru, Fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute and an analyst at the Economic Policy Research Foundation of Turkey

Turkish political culture harbours both intense admiration and resentment towards Europe. These feelings coexist, but they shift in emphasis. Every non-Western country, from Japan to Brazil, has replicated aspects of Western modernity, but the Kemalist regime in Turkey went further than any other. The Ottoman Empire had been the seat of the Islamic caliphate, governed by a culture that was distinct from that of Europe. The Kemalists did not just reform the economy and the military, they pursued cultural reform – linguistic, sartorial, religious – designed to make the country Western.

There were holdouts to these reforms, people who thought that giving up Turkey's distinctiveness was a disaster, a kind of spiritual self-mutilation. They were poets and polemicists, often of Islamist or pan-Turkic persuasion, who believed that restoring the identity of the Empire would allow Turkey to be great again. The Erdoğan government is a product of these movements. The irony is that their kind of romantic nationalism – the assertion of religious and ethnic distinctiveness, the drive towards national competition – is all immensely European. The conflict between these tendencies used to be described as Islamism versus secularism, East versus West. In reality, they are two different ways of obsessing over Western supremacy.

The dominant paradigm in current Turkish nationalism – going far beyond the Erdoğan government – is that Western power stemmed from a willingness to engage in immoral conduct. Western countries chose to colonise, plunder and cheat their way to the top and they now reap the benefits. The Ottomans, meanwhile, made moral choices and fell behind. Turkish politics today still mimics the West, but the aim is to beat it, not join it.

Turkey rightfully decries Europe’s double standards but fails to see the ways in which it resembles some of Europe’s worst qualities. All this weighs down relations. Trade, visa arrangements, even basic diplomatic exchanges entail needless emotional friction.

‘History is not destiny. Many EU nations were at daggers drawn until the mid-20th century’

Murat Metinsoy, author of The Power of the People: Everyday Resistance and Dissent in the Making of Modern Turkey, 1923-38 (Cambridge University

Press, 2021)

All modern governments lean on historical events to justify their policies. Whereas liberal-integrative polities tend to highlight cooperation, nationalist-conservative governments like to parrot past conflicts. This ‘memory engineering’ by states matters as much as what actually happened in the past. Every society can portray itself as victim or perpetrator; this is especially true in the case of Turkey and Europe, who have shared a millennium of cooperation and competition.

Europeans have often seen the Turks as the barbaric, despotic eastern ‘other’ of the Christian West. The fall of Constantinople and the Ottomans’ expansion towards the continent terrified Europe. Then, as the industrial European powers overcame the Turks, western meddling in Ottoman politics disturbed even the most ardent westernist voices within the Empire. Turkish grievance with Europe peaked with the Treaty of Sèvres, which can be described as a ‘Turks’ Versailles’. The Turks nullified the treaty through an independence war, but the establishment of a Turkish state did not produce an anti-Western political ideology; on the contrary, the Republic pursued a radical westernisation policy in the hope of joining the European club.

Security anxieties brought on by the First World War kept Turkey out of the Second and led the country to join NATO in order to protect itself from foreign attacks. However, Turkey’s efforts to join the EU had unintended consequences, strengthening the hand of anti-Western Islamists. In the last 20 years, the EU’s stress on democracy has allowed Turkey’s Islamists to overcome the secular state’s bureaucracy and civil society. In this, history has served as a means of reconciliation. As Erdoğan’s votes dwindle, efforts to offset his decline have revived rhetoric of ‘European cultural imperialism’, while ‘Western plots’ justify the retreat from democracy demanded by the EU. But history is not destiny. Many EU nations were at daggers drawn until the mid-20th century (and beyond). Politics will always determine which historical memories are recalled, and how.

Source: History Today Feed