It Was a Dark and Stormy Night... - 4 minutes read

How much should we exercise our imaginations in writing about the past? As any historian knows, sometimes it has to be a great deal. Trying to reconstruct any episode in history can be a complex interplay between what we know and what we can use to fill in the gaps – what we can hypothesise, speculate, deduce or simply imagine. Imagination may be an important tool in striving to understand the lives and actions of historical figures, a means by which we can seek to grasp experiences, feelings and motivations radically different from our own. It’s impossible to think yourself into the life of another person, but attempting to do so can be a valuable first step in gaining a rounded picture of our historical subjects.

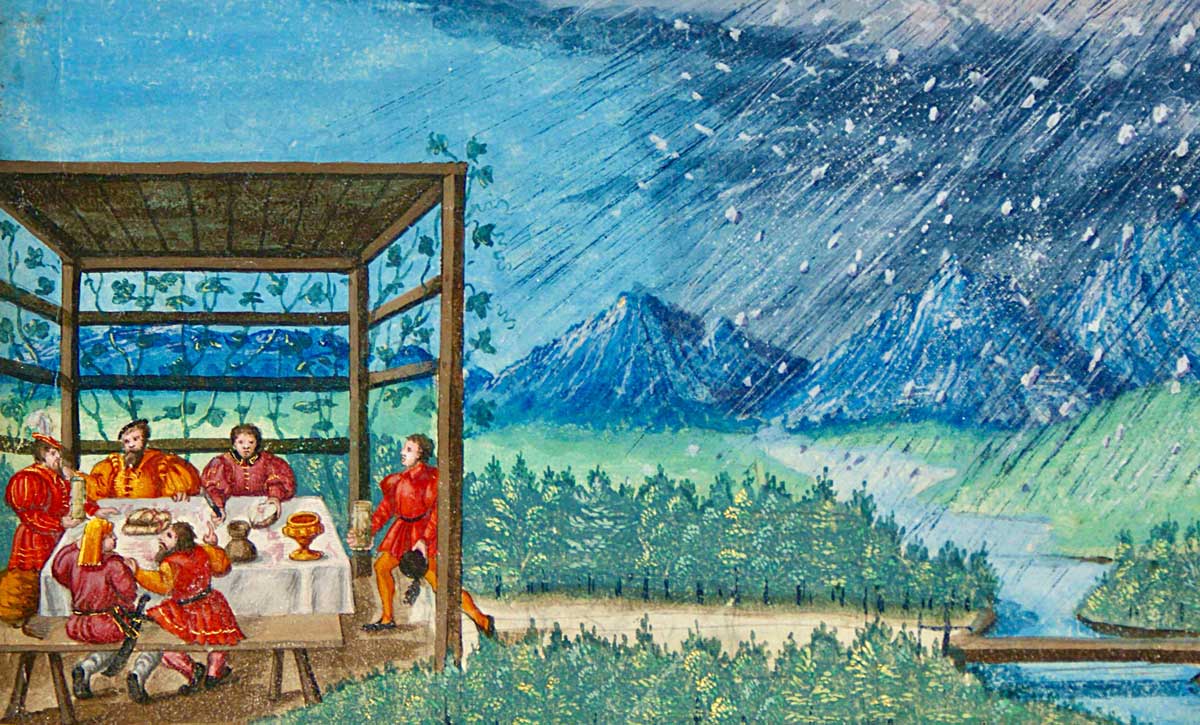

And how should that thinking make its way into our writing? One currently popular means of injecting a bit of imaginative colour into history books is with what somebody once described to me as ‘the dawn over the Thames opening’. You’ll know the kind of thing. You turn to the first page of a book and read: ‘England, 1430. Dawn is breaking over the dark waters of the Thames. The sky is gradually turning red, but on this winter morning there’s a keen chill in the air. Down a shadowy street, a small group of men are shuffling towards the river ...’

The purpose of such an opening is to plunge the reader into the middle of the story, to bring it alive, and to get the imagination engaged – especially important if the author fears the historical setting may otherwise be off-puttingly distant for the modern reader. This is how many people starting out in writing history for a general audience are encouraged to proceed; it’s the product not so much of in medias res as of media training. It is ubiquitous, so presumably readers and writers alike find it useful.

Of course, it can be overdone. I’ve sometimes read books in which every chapter seems to begin with variations on this device, showing an evident strain on the author’s imaginative powers. When all else fails, at least there’s usually something to say about the weather. ‘It was a sunny day in April and King Henry II of England was looking out of a window.’ ‘The December wind was blowing cold, so Queen Eleanor wrapped her cloak more tightly around her and shivered. What a day, she thought!’ For the reader this offers the bonus challenge of trying to forecast what kind of weather might open the next chapter. Now we’re going to Normandy, 1163; I wonder if it’ll be raining?

I admire historians who can do this well, because it doesn’t come naturally to me. I find writing it difficult and reading it makes me quite illogically picky. I want to ask ‘well, how do you know it was raining?’ The author could reasonably answer ‘because it was winter, and anyway why does it matter?’ Fair enough. It’s a harmless bit of imagination and perhaps it really does help readers get into the story.

But whether readers care or not, it does matter whether the details of our narratives – all details, perhaps even the specific state of the weather on a particular day – come from our sources or from our imagination. A sensible deduction is one thing, an unthinking assumption another. The latter can mean we’re not so much trying to imagine the past as slotting our ideas about it into pre-determined patterns. This kind of writing, when not done well, slips easily into clichés and stereotypes and the boundary between fact and imagination quickly becomes blurred.

It might not matter in talking about the weather, but it matters very much when we start asserting that we know the thoughts or feelings of people in the past. When historians do that, we may reveal more about ourselves than about the people we’re describing. If the imagined thoughts of long-ago figures end up sounding exactly like the thoughts of 21st-century western secular historians, what are they really adding to our knowledge of the past?

This is where we need to be most careful with our language, attentive to our assumptions and scrupulous about our sources. There’s a huge difference between ‘she thought’, ‘she must have thought’ and ‘she might have thought’. If you say ‘she thought’, the reader at least deserves to know whether and how we know that for sure – or if it’s simply the historian’s imagination at work.

Eleanor Parker is Lecturer in Medieval English Literature at Brasenose College, Oxford and the author of Conquered: The Last Children of Anglo-Saxon England (Bloomsbury, 2022).

Source: History Today Feed