Broken Windows | History Today - 6 minutes read

In 1982, George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson published an article in the Atlantic which transformed policing in the United States. Titled ‘Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety’, it argued that city police should aggressively clamp down on low-level street disorder – panhandling, prostitution, loitering ‘youths’ – in order to prevent more serious crime. Responding with enthusiasm, police departments across the US began implementing their own ‘broken windows’ or ‘zero tolerance’ strategies, saturating poor neighbourhoods with police and dramatically escalating their arrest rates for minor offences.

Broken windows policing was a critical driver of mass incarceration in America. Yet, significantly, its origins lay not in the feverish cries for ‘law-and-order’ from conservative firebrands such as Barry Goldwater, or President Reagan. Rather, the idea arose out of liberal attempts to reform law-enforcement after the urban uprisings of the 1960s. Indeed, Kelling and Wilson rooted their Atlantic article in research they had undertaken at the Police Foundation, a think-tank established in 1970 to help pioneer ‘community policing’ in cities across America.

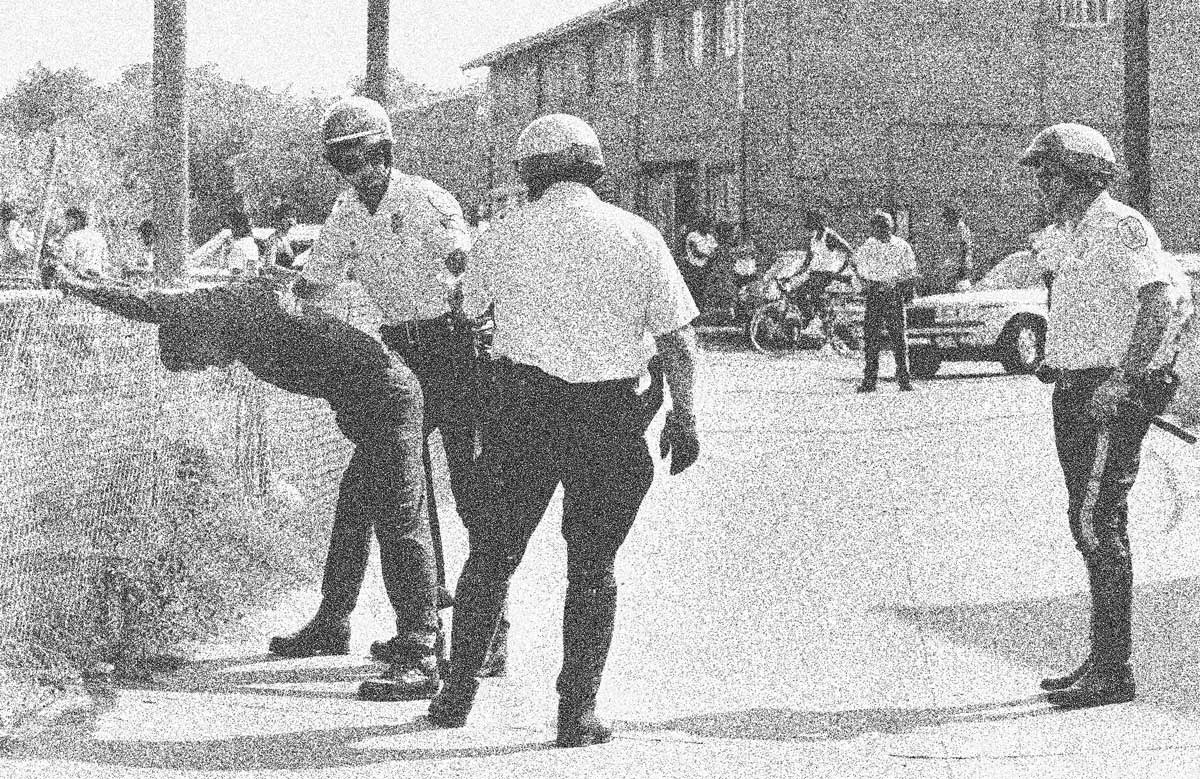

In the four years after 1964, a wave of urban rebellions swept across the US, often precipitated by racist acts of police violence: over 150 cities erupted in 1967 alone. The Kerner Commission, established that year by President Lyndon B. Johnson to uncover the causes of the disorder, concluded that for many African Americans the police ‘have come to symbolize white power, white racism, and white repression’. ‘The fact is’, the report added, ‘many police do reflect and express these white attitudes.’

For liberal lawmakers and some police officials, the solution lay in strengthening the links between local law enforcement and the communities they served. This meant officers getting out of their patrol cars and familiarising themselves with the neighbourhoods they policed. In many cities, police began attending community association meetings, giving talks at local schools and offering ‘ride alongs’ for curious local residents.

Drawing together this nascent community policing movement was the think tank Police Foundation. Established in 1970 with a multi-million dollar grant from the Ford Foundation – a left-leaning philanthropic organisation – the Police Foundation was designed to act as a catalyst for liberal police reform nationwide, providing funds and expertise to reforming police chiefs across the country. With the federal government largely focused on bolstering police arsenals with new weaponry and equipment, Ford hoped to assist the emerging community orientated approaches.

Initially, rank-and-file officers greeted the Police Foundation with disdain. Its community policing projects were viewed as ‘soft’; a shadow of ‘real’ police work. Many also pointed to its links with the Ford Foundation; Ford had spent the 1960s assisting the Civil Rights movement in America (even funding a few ‘Black Power’ groups), acquiring a reputation as a home for ‘bleeding heart liberals’. Its transition into police reform was therefore regarded with intense suspicion: ‘When an organization having a history of financing Black Powerites sets up an agency to develop more modern police forces’, one Ohio newspaper observed bitterly, ‘the police had better watch out.’

Ford worked hard to counteract this notion that its efforts were a threat to police power. The Police Foundation was set up as a separate entity and the board staffed with high-ranking police officers and conservative academics. This signalled the Foundation’s intention to work with police in the quest for reform; reform was necessary, but it had to be done in a way ‘acceptable to the law enforcement community’. This, however, limited the kind of reform the Foundation was able to contemplate; by opting to work within the law-enforcement community, its influence now depended on the cooperation of the police.

During the 1970s, the Police Foundation collaborated with local police departments on a series of experiments into community-orientated patrol. Led by George Kelling, these suggested that foot patrols reduce crime. By walking through the neighbourhood, the police were better able to work with its residents; it encouraged them to enforce order in the streets, creating an atmosphere less conducive to serious crime.

This emphasis on ‘order-maintenance’ policing formed the basis of Kelling and Wilson’s 1982 Atlantic article, ‘Broken Windows’. To justify this shift in police practice, they sketched a vision of low-level urban disorder left unchecked: ‘If a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken.’ This then attracts ‘drunks, addicts, rowdy teenagers, prostitutes, loiterers’, creating an intimidating atmosphere that breaks down community controls – ultimately allowing more serious crime to flourish.

‘Broken Windows’ offered a vision of community safety with an enhanced role for the police. While some sociologists have since cast doubt on the theory, many police and politicians adopted it with enthusiasm. Broken windows-style policing offered departments a way to increase their funding, power and discretion and offered elected officials a ‘scientific’ and more enlightened mode of crime control that could tackle voter concern over street crime.

The strategy soon swept across the US. Kelling and Wilson’s article directly informed mayor Rudy Giuliani’s ‘zero-tolerance’ policing initiative in New York City during the 1990s, which saw the NYPD aggressively enforce misdemeanour laws against public drinking, graffiti and turnstile-jumping. Giuliani’s apparent success ‘cleaning up’ New York City received global attention and the broken windows strategy was embraced by US mayors across the political spectrum.

Reflecting later in life, Kelling remained adamant that his theory was a pioneering example of ‘community policing’. When it was applied in practice, however, he acknowledged that police had sometimes used the strategy to stop, frisk and arrest increasing numbers of Americans – focusing their efforts disproportionately on Black communities. During the War on Drugs of the 1980s and 1990s, it was also used to legitimise the aggressive sweeps of entire neighbourhoods. And from New York City to San Francisco, broken windows policing drove a shift towards punitive solutions to a range of social problems, including homelessness, addiction and mental health.

Calls for the ‘defunding’ or ‘abolition’ of the police have grown in recent months. In contrast to these demands, the Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden has instead pledged more money for the police: $300 million for enhanced ‘community policing’. As the history of community policing shows, the strategy has not always been effective at restraining police power. By leaving reform largely in the hands of the police, the strategy was rapidly co-opted into a mechanism that knit the police ever more tightly into certain neighbourhoods, often leading to a cycle of surveillance, arrest and incarceration.

Sam Collings-Wells is a PhD student at the University of Cambridge studying policing in the Empire and the UK.

Source: History Today Feed