Inside the Rise and Fall of a Migrant-Shelter Magnate - 23 minutes read

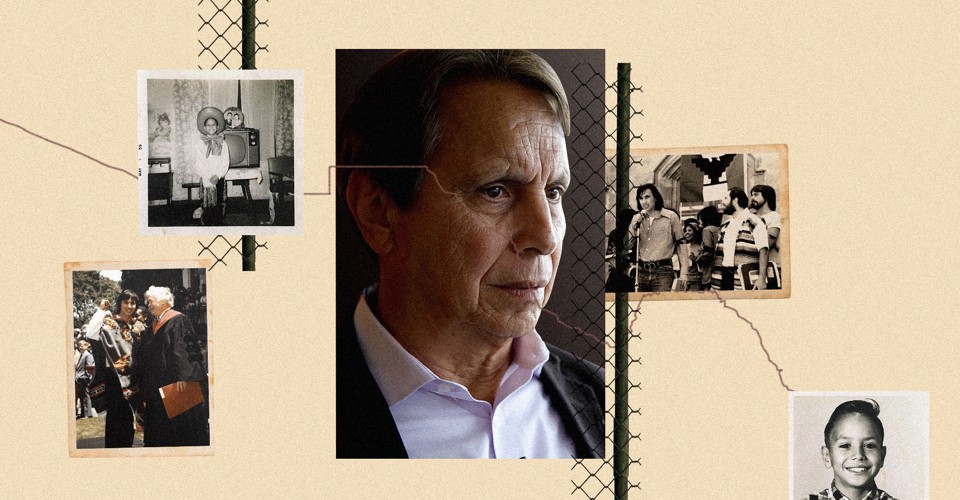

Trump's Family Separations Brought Down Juan Sanchez

Trump's Family Separations Brought Down Juan SanchezJuan Sanchez was once hailed as a champion for social justice. Then his network of shelters started taking in children split from their relatives.

AUSTIN, Texas—Juan Sanchez, the founder of America’s largest network of shelters for detained migrant children, greeted his employees at the company’s Thanksgiving potluck last November. “How you doing, brother?” he asked. “Como estás, mija?” The employees seemed preoccupied. Their company, Southwest Key, had been in the national spotlight for months. Since the Trump administration began separating families at the U.S.-Mexico border last year, Southwest Key has been integral to housing the thousands of children split from their parents and other relatives. “I saw you on TV yesterday,” a worker told Sanchez in Spanish. “Y qué estaban diciendo?” Sanchez replied—“What were they saying?” “About Casa Padre,” she said, referring to a Walmart Supercenter that Sanchez had converted into a cavernous shelter. “This year has been long,” another employee said with a sigh. Lean and still boyish at 71, a former Golden Gloves champ raised in a border barrio who came of age in the Chicano-rights movement, Sanchez was in the middle of his fiercest fight yet. His Walmart facility had become a symbol of Trump’s industrial-scale separation policy, and he’d weathered months of criticism: that he was complicit in the destruction of migrant families, that his $1.5 million salary was unseemly for the operator of a charity, and that he’d failed to prevent sexual abuse in his shelters as Southwest Key grew into a massive operation. Within months of our interview last fall, he would leave the company he built from scratch. ‘The Separation Was So Long. My Son Has Changed So Much.’ Are Children Being Kept in 'Cages' at the Border? All along, however, Sanchez maintained that he didn’t change—the political climate did. For decades, civil-rights leaders had lauded him as a champion of social justice who was providing migrant children excellent care. By the time we sat down in November, former allies—including his own employees—had abandoned him, arguing that the moral meaning of his shelter empire had changed as the Trump administration weaponized the country’s immigration bureaucracy. As if to rehabilitate his image, Sanchez had invited me to tour one of the shelters and to introduce me to his childhood confidants in South Texas. But the week after my first visit, Sanchez abruptly canceled my next trip when The New York Times exposed a pattern of financial mismanagement at Southwest Key. He did not respond to further requests for comment.

At the potluck, however, Sanchez was bullish. In his office, decorated with framed quotations from Che Guevara and Martin Luther King Jr., he explained to me that critics were jealous of his success and would prefer to see him laboring in the cotton fields, as he had in his youth. “Not many Latinos I know of run a half-billion-dollar company,” he told me. “That pisses people off.” Juan Sanchez grew up in Brownsville, Texas, the southernmost city along the U.S.-Mexico border, in the Rio Grande Valley. In his neighborhood, families sprawled across the international line, and English was hardly spoken at home. When he was a young schoolkid in the 1950s, teachers punished Sanchez for speaking Spanish in class, he told the journalist Maria Hinojosa of NPR’sLatino USA last summer. One teacher claimed she couldn’t pronounce Juan, so she decided to call him Johnny instead. “They were always trying to change your identity,” Sanchez told Hinojosa.

After his father died, when Sanchez was 14 years old, he began working the fields in California during summer breaks to support his family. His escape was the boxing ring, where he thrived on competition. “It’s you and the other guy, and you try and hurt each other,” he told Hinojosa. He learned to be disciplined and to “hit very hard.” In college and graduate school in the 1970s, Sanchez channeled that fighting spirit into activism. “He was always a rabble-rouser,” Leonard Cash, a former classmate at St. Mary’s University, told me. “Always angry.” Later, at the University of Washington, where Sanchez got his master’s degree, he and a group of Chicano-rights activists occupied the university president’s office to pressure the school to hire more faculty members of color. In one photo, wearing an Army-surplus shirt and a fedora pulled low over his eyes, Sanchez has his boots propped up on the president’s desk. “What we were fighting for was to have some representation,” Sanchez told me. Ellen Sanchez, Juan’s ex-wife, who kept his last name after their divorce in the 1990s, met him at a protest to pressure the University of Washington to serve lettuce picked by the United Farm Workers, the union led by Cesar Chavez. Juan went on to pursue a doctorate in education, choosing Harvard “so he could out-credential the people who would try to keep a Latino out,” Ellen told me. For his dissertation, Sanchez studied grade schools in the Southwest that embraced Chicano culture, essentially searching for a model where a Juan would get the same chances as a Johnny. At his Harvard graduation, he wore a serape instead of a robe. “That year, I was the only Latino that got a doctorate from the School of Education,” Sanchez recalled to me. He posed for a photograph with his fist in the air, a Harvard Yard radical. “I was making a statement,” he said. “I wanted people to remember me that way.” Sanchez returned to Brownsville to work at the Esperanza Home for Boys. A Catholic priest, Father Jerry Frank, had founded the reformatory as a local alternative to juvenile incarceration and was looking for a new director. Having risen from Brownsville’s poorest neighborhood to the Ivy League, Sanchez seemed like an ideal role model for troubled youth, Frank told me. “He was very alive, very confident,” Frank said, “maybe a little cocky.”

Within a year, Frank recalled, Sanchez outstripped his predecessor’s ambition, absorbing Esperanza under an umbrella organization he eventually named Southwest Key. On Sanchez’s professional résumé from that time, listed under “major accomplishments,” is “wrote major proposal … to establish an emergency shelter for alien children.” To help manage the growing company, he hired Angela Luck. “I was his right hand,” Luck, who became deputy executive director, told me. Sanchez was a good boss who gave employees the freedom to experiment, Luck said, and they soon found opportunities to expand: “We were all fairly aggressive about growth.” In the 1980s, roughly 1 million Salvadorans and Guatemalans migrated to the United States fleeing civil war, repression, and poverty. With thousands arriving in Brownsville, Luck applied for a contract to manage a tent city housing asylum-seeking families. “There was a commitment to not separate children and families,” Luck recalled. Contracts for sheltering unaccompanied minors soon followed, and as the flow of youths to the U.S. border increased over the next two decades, so too did the company’s revenue. In her 15 years with Southwest Key, Luck oversaw a budget that grew from several hundred thousand dollars to more than $40 million. “I don’t know that we ever turned down an offer that someone made that allowed us to grow,” she said. But Sanchez’s ambition could also curdle into “yelling and occasionally throwing things.”

“We were very entrepreneurial and innovative,” Arjelia Gomez, Southwest Key’s former chief operating officer, told me. But “he was ruthless at times.” Sanchez “was driven by anger about the racism and discrimination he’d faced in his life,” said Luck, who left the company in 2002, after seeing no further opportunity for advancement. He “was very motivated to show that he, as a Latino from the valley who grew up poor, could become a very successful, powerful person,” Luck added. “He wanted to prove himself.” Rachel Howell, a former vice president there, told me Sanchez “didn’t let anything get in his way.” “It’s the part of Juan that helped him become successful,” she explained. “But it was also his Achilles’ heel.” By 2013, Sanchez had become a board member of one of the most prominent Latino-advocacy organizations in the country, the National Council of La Raza, now called UnidosUS. That year, at the organization’s gala in New Orleans, he ascended the stage to receive one of NCLR’s highest honors, the Affiliate of the Year award. “The crux of our work is about creating opportunities for our gente,” Sanchez told the crowd. “This is a great time to be a Latino in this country!” Two months later, employees at a Southwest Key shelter in Phoenix were busy preparing for a visit from Sanchez, or “El Presidente,” as he was known to staff. It was an exciting first day on the job for Sibila Quiroz, then a recent college graduate. “My family are immigrants, and I wanted to always give back,” she told me, “so I thought it was the best opportunity.” Sanchez greeted the staff with affection and warmth, she said. “He really came from where these kids are from and rose all the way to the top,” Quiroz recalled thinking. “It’s like the symbol of the American dream.”

But within just four years, Quiroz’s feelings about Southwest Key would fundamentally change, as she began to suspect that the company put its own growth before protecting the minors in its care, including from sexual abuse. “Southwest Key has the potential to be an amazing place,” Quiroz told me. “But instead, we’re so focused on growing at this fast pace that all of these mistakes are bound to happen.” Over time, Quiroz worked her way up to case manager, identifying family members who could sponsor migrant minors, and finally became an English teacher at the facility. She still keeps a box of heartfelt letters, drawings, and friendship bracelets that detained youths gave her as parting gifts on their release. “You’ve never cared about the color of my skin or where I came from,” Quiroz read aloud to me from a note by a Honduran teen. I met one of her students in Phoenix on a bright morning last fall. Fearing retaliation from American immigration officials, though he’s living in the country legally, the former student requested anonymity; like Quiroz, he’d never talked to a reporter before. Soft-spoken and bookish as a kid, he said he suffered from severe anxiety during his 11-month detention at Southwest Key in 2017. To help occupy his mind, Quiroz brought him extra reading material from the world outside, he recalled. “I’d always read the books she brought me so that I’d have something to do,” he said. But darker traumas at Southwest Key would later fuel yet more anxiety.

During Quiroz’s time at Southwest Key, the number of Central American youths arriving at the U.S. border fleeing criminal gangs and trying to reunite with family skyrocketed to unprecedented levels. The Obama administration, in a scramble, inked new deals with Sanchez, and the company’s revenue more than doubled from 2012 to 2014, according to tax disclosures. By 2016, the organization’s footprint in Arizona had more than doubled, to eight shelters, and Quiroz began to worry that the company’s hiring standards had eroded with the rapid expansion. Read: The invisible children of the Trump administration Quiroz told me she was unnerved by inappropriate displays of dominance over the minors by one of her co-workers, a guard named Levian Pacheco. In August 2016, she said she witnessed Pacheco yell at a teen for insufficient “respect,” and she filed a complaint with management. “I didn’t feel comfortable with him working with children of such a vulnerable population,” she told me. Responding to Quiroz’s complaint in an email, a manager promised that Pacheco’s supervisor would follow up with him. But Pacheco remained employed with the company. A year later, in July 2017, one of Quiroz’s students asked to speak with her privately. “Teacher, es normal que unstaff te toque el cuerpo?” he asked, according to a report Quiroz filed with Southwest Key management that day, a copy of which she later shared with me. “Is it normal for staff to touch your body?”

In total, eight minors, including Quiroz’s bookish student from Phoenix, would come forward with accounts of sexual abuse by Pacheco, court documents show. One boy was immobilized and dulled by pain medication after a surgery when he awakened to Pacheco performing oral sex on him. (Asked for comment on Pacheco, a spokesperson for Southwest Key said: “When we learned of possible abuse, we acted immediately by calling law enforcement and suspending him,” and worked with investigators “to ensure Mr. Pacheco was held accountable for his actions.”) “Finding out later that it was Levian who did this—that was infuriating,” Quiroz told me, her eyes welling up, “because I wasn’t the only one who raised concerns about him.” Disillusioned, she resigned from Southwest Key. “We didn’t do what we needed to do, and these kids had to suffer because of it,” she said. But Pacheco’s abuse—and Southwest Key’s flawed safety record—would not become widely known for another year, when the separated children began arriving by the hundreds. In Sanchez’s hometown of Brownsville, beneath a cracked layer of black paint, a Walmart logo is visible on a tall sign facing the fast-food-laden Highway 48. The vast Casa Padre parking lot is that of a typical big-box store, except the vehicles belong not to shoppers, but to workers and guards. Noisy flocks of grackles perch in the trees above yellow barriers that read KEEP OUT. In the summer of 2018, roughly 1,400 migrant minors slept inside. Hundreds had been separated from their parents.

Customs and Border Protection technically does the separating at Border Patrol stations throughout the Southwest, facilities that drew public outrage earlier this summer following reports of squalid cages, frigid temperatures, and substandard food. Adults are sent to jails run by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, while the kids are placed in shelters contracted by the Office of Refugee Resettlement. The largest such contractor is Southwest Key—and its largest shelter is Casa Padre. Commissioned by the Obama administration, Casa Padre was designed to expand or contract quickly, based on the difficult-to-predict flow of minors to the border. There, they could access medical care, dental care, hot meals, recreation, and bilingual education—a far more kid-friendly environment than the Border Patrol’s network of hieleras, or “iceboxes.” Southwest Key shelters were normally far smaller than Casa Padre. Sanchez toured the empty Walmart during renovation and thought, This is never going to become a shelter, he recalled to NPR’s Hinojosa. “But the people who made it were very creative and innovative.” The contract required that children have access to natural light, for example, so they punched skylights through the roof of an otherwise windowless warehouse. “It’s amazing,” Sanchez said. “The largest licensed facility in the world.” The apotheosis of his empire, Casa Padre would come to attract the intense public scrutiny that triggered his downfall.

Lawmakers and cable-news outlets descended on Casa Padre in the summer of 2018. “Advocates for immigrants had told me that hundreds of boys were being stashed in this child prison,” Democratic Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon said in an interview. “So I wanted to get to the bottom of it.” He arrived at Casa Padre in June, at the height of the initial family-separation crisis, and requested access to the children. Instead, Southwest Key staff called local police to remove him. A video of the encounter went viral, spurring protests against what demonstrators viewed as Southwest Key’s complicity in separating families. Sanchez later said he personally opposed the policy, but far from joining demonstrators, he gathered about 150 employees to confront them outside his Austin headquarters in a kind of counterprotest. He argued that Southwest Key was not responsible for what the administration was doing. “We’re not the bad guys,” Sanchez told the local TV station KVUE. “We’re the good guys.” The day after his counterprotest, in an interview with Hinojosa, Sanchez called his decision to accept separated kids a “moral dilemma.” He framed it as a simple binary: Take all the kids—separated babies as well as unaccompanied teens—or take none. Sanchez said he believed that refusing to accept separated children would provoke the Trump administration into retaliating by revoking all his contracts. “If we would not have taken these kids, we would have had to give this up,” Sanchez told Hinojosa. “We would have lost everything.” That would do more harm than good, Sanchez argued, because filling the void would be for-profit companies, “not run by Latinos,” that cut corners to make money.

But Sanchez was no longer the activist underdog—he was the CEO of an industry juggernaut. In just the past 10 years, Southwest Key has taken in $1.7 billion in government contracts. The company is so large that the government relies on it to keep the already overstressed shelter system afloat. “Shutting down the shelters would create a crisis for the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement,” a former senior official told ProPublica. Sanchez could have used such leverage to pressure the Trump administration to end separations, argued Howell, the former Southwest Key vice president. He could, she said, “do like he used to do and march in the streets and say, ‘We aren’t gonna do this.’” “The Juan Sanchez I knew,” Luck said, “would have fought against it.” Merkley spoke to Sanchez by phone soon after his abortive visit to Casa Padre. “I asked Juan Sanchez to take a stand against child separation,” Merkley recalled. “He turned me down. He said, ‘I cannot take that stand.’ He said, ‘I might lose contracts if I take that stand.’” (The Southwest Key spokesperson told me the organization has always opposed family separations, which cause “unnecessary and inhumane psychological damage on the very children our organization is committed to helping.”) To Sanchez’s allies, he was being turned into “a scapegoat by the left,” as Ellen Sanchez put it. The real problem was Trump’s policies, she said, but her fellow liberals “just want to find someone to hang.”

At first, UnidosUS stood by Southwest Key. “For a long time, we defended them,” Lisa Navarrete, an adviser to UnidosUS President Janet Murguía, told me. But standing with Sanchez “became untenable,” she said, when reports of sexual abuse surfaced later that summer. More than a year after Sibila Quiroz’s student approached her about Pacheco, the first report detailing allegations about the guard appeared in ProPublica, in August 2018. Authorities ultimately charged Pacheco with 11 sex offenses, and the story prompted the Arizona Department of Health Services to review Southwest Key’s safety record. In a scathing letter to Sanchez, the agency’s director, Cara Christ, said the company had not completed background checks and the fingerprinting of employees. Southwest Key displayed an “astonishingly flippant attitude” toward vetting, Christ wrote. (Pacheco, ProPublica reported, had worked for four months at Southwest Key before he received a background check. He did not have a prior criminal record.) The safety issues weren’t isolated. Regulators inspecting the company’s 16 facilities in Texas have found almost 300 health-and-safety violations in the past three years.It once hired an ex–Border Patrol agent to work at Casa Padre despite his previous charges for possession of child pornography. From 2014 to 2018, 178 allegations of sexual assault by staff at shelter contractors, including Southwest Key, were referred to the Justice Department. After Christmas, weeks after my interview with Sanchez, Arizona regulators shut down two Southwest Key facilities in the state after videos emerged of staff physically abusing children. According to the Southwest Key spokesperson, the company has applied to reopen both locations. (Southwest Key’s federal overseer, the Administration for Children and Families at the Department of Health and Human Services, did not respond to requests for comment for this story.)

Quiroz’s former student, now 19, attends a community college in Phoenix, where he’s refining his English and trying to turn his love for video games into a career as a computer programmer. He hasn’t told his family back in Honduras about what happened at Southwest Key “because it’s embarrassing,” he said. In January, Levian Pacheco was sentenced to 19 years in prison for sexually abusing minors. Still, “it was worth it, all that happened to arrive here,” the teen said. “Because now I go to school, and I have friends. I feel secure in the street when I go to the mall or I go shopping at Walmart.” “Everything about the shelters is secret,” he told me. “I want people to know about the problems.” "At the risk of seeming ridiculous, the true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love,” Sanchez said, reading aloud from the Che Guevara poster in his office, after the Thanksgiving potluck. “I find that very meaningful in the work that I do.” He told me he’d made peace with his role in family separations. “There is no dilemma for me,” Sanchez said. “I sleep very well.” He said he’d institutionalized his early activism by hiring a diverse staff, opening a charter school, and sheltering thousands of migrant children. “I went from that kind of activism,” he said, “to now saying, ‘How do we do something about it?’” He only wished Southwest Key were “two or three times as big, because we could affect the lives of thousands more kids.”

Critics, Sanchez told me, “would love to see us close our door, but they haven’t been able to make us.” Days after we met,The New York Timesreported that Southwest Key “possibly engaged in self-dealing with top executives.” A former Internal Revenue Service official who reviewed the organization’s tax returns for the Times told the paper that Sanchez’s financial dealings amounted to “profiteering.” The report spurred a Justice Department investigation into Sanchez’s finances. Then, in March, after 32 years of leading Southwest Key, Sanchez resigned. In an email to staff, he wrote, “Widespread misunderstanding of our business and unfair criticism of our people have become a distraction our employees do not deserve, and I can no longer bear.” Three other top executives have left the company in the months since. Asked for comment on the Times report, the Southwest Key spokesperson said the company has a new executive team in place. Last month, newly released tax records showed that Sanchez’s most recent compensation package was worth $3.6 million—more than double the $1.5 million salary he defended last summer. “He was forever angry about privilege,” Luck said. “I think ultimately, at some point, that became his ambition to have the same thing.” In the converted Walmart, Luck saw a betrayal of what she and Sanchez once sought to create. “Our entire mission was to keep kids out of institutions,” she said. “Instead, they built one.”

Source: Theatlantic.com

Powered by NewsAPI.org

Keywords:

Juan Sánchez Moreno • Juan Sánchez Moreno • Social justice • Austin, Texas • Juan Sánchez Moreno • Thanksgiving • Potluck • Presidency of Donald Trump • Mexico–United States border • Spanish language • Walmart • Golden Gloves • Barrio • Chicano • Civil and political rights • Middle class • Walmart • Symbol • Donald Trump • Industrial Revolution • Racial segregation • Policy • Immigration • Family • California County Routes in zone S • Sexual abuse • Vị Thanh • Civil and political rights • Social justice • Immigration • Health care • Allies of World War II • Employment • Morality • Empire • Presidency of Donald Trump • Nation state • Immigration • Bureaucracy • South Texas • The New York Times • Potluck • Che Guevara • Martin Luther King Jr. • Hispanic and Latino Americans • Juan Sánchez Moreno • Brownsville, Texas • Mexico–United States border • Rio Grande • Family • English Americans • Homeschooling • Spanish language • Social class • Journalist • Maria Hinojosa • NPR • Slatino (Debarca) • California • St. Mary's University, Texas • University of Washington • Loretta Sanchez • Master's degree • Chicano • Civil and political rights • Activism • Color • Military surplus • Shirt • Fedora • Boot • Divorce • University of Washington • Lettuce • United Farm Workers • Cesar Chavez • Doctor of Education • Harvard University • Latino • Serape • Latino • Harvard Yard • Remember Me (T.I. song) • Roman Catholic Diocese of Brownsville • Prison • Brownsville, Brooklyn • Poverty • Ivy League • Confidence • Alien (law) • Hierarchy • Value (ethics) • Employment • Political freedom • El Salvador • United States • Civil war • Poverty • Brownsville, Texas • Tent city • Contract • Unaccompanied Minors • Chief operating officer • Racism • Discrimination • Latino • Poverty • Vice President of the United States • Achilles Heel (Homeland) • Latino • National Council of La Raza • New Orleans • National Council of La Raza • Latino • Phoenix, Arizona • El Presidente (film) • American Dream • Emotion • Minor (law) • Sexual abuse • English language • Friendship bracelet • Parting Gifts • Honduras • Phoenix, Arizona • Anxiety • Anxiety • Presidency of Barack Obama • Tax • Arizona • Invisible Children • Presidency of Donald Trump • Management • Email • Management • Phoenix, Arizona • Sexual abuse • Analgesic • Oral sex • Child abuse • Law enforcement • Brownsville, Texas • Walmart • Fast food • Ontario Highway 48 • Big-box store • Perch • U.S. Customs and Border Protection • United States Border Patrol • U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement • Child • Office of Refugee Resettlement • Barack Obama • Health care • Dentistry • Bilingual education • Walmart • NPR • Apotheosis • News broadcasting • Democratic Party (United States) • United States Senate • Jeff Merkley • Oregon • Police • Protest • Demonstration (protest) • Television station • KVUE • We're the Good Guys • Child • Presidency of Donald Trump • Activism • Underdog (term) • Semi-trailer truck • Bremgarten–Dietikon railway line • Office of Refugee Resettlement • ProPublica • Linda Sánchez • Presidency of Donald Trump • Vice President of the United States • Juan Sánchez Moreno • Juan Sánchez Moreno • Take That • Take That • Family • Causality • Cruelty to animals • Psychological abuse • Organization • Scapegoating • Reality • Donald Trump • Liberalism • President of the United States • Janet Murguía • Sexual abuse • ProPublica • Arizona Department of Health Services • Background check • Fingerprint • ProPublica • Background check • Criminal record • Texas • United States Border Patrol • Indictment • Child pornography • Sexual assault • Employment • Independent contractor • United States Department of Justice • Christmas • Arizona • Domestic violence • Federal judiciary of the United States • Administration for Children and Families • United States Department of Health and Human Services • Phoenix, Arizona • English studies • Programmer • Family • Honduras • Child sexual abuse • Minor (law) • Worth It All (Meredith Andrews album) • Adolescence • Walmart • Che Guevara • Thanksgiving • Potluck • Family • Charter school • Immigration • New York (magazine) • Self-dealing • Internal Revenue Service • United States Department of Justice • Email • Employment • Business • Employment • LSWR S15 class • Motivation • Walmart •