Park Life | History Today - 6 minutes read

December 2019 marks the 70th anniversary of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. The Act created the legal framework for National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty and introduced reforms designed to allow greater access to the countryside, as well as new approaches to the protection of nature and landscapes. It was a pivotal piece of legislation for the conservation movement, but it is often forgotten that it was also an integral part of the reconstruction programme after the Second World War, sitting alongside health, housing, education and the welfare state.

The concept of protecting the cultural, natural and aesthetic qualities of landscape can be traced back to the early 19th century. William Wordsworth was one of its earliest and best-known advocates, writing extensively about his profound love of the Lake District. Significantly, however, as early as 1810 he described the area as ‘a sort of national property, in which every man has a right and interest who has an eye to perceive and a heart to enjoy’, suggesting that beautiful landscapes were a national asset that should be available to all.

As the century progressed, interest grew in preserving beautiful landscapes and ensuring they were accessible, encouraged by increasing unregulated development and the enclosure of previously common land. The cause was given added impetus as concerns grew about the squalid living conditions of the rapidly increasing urban population. This led to the creation of some of our best known conservation organisations, including the Open Spaces Society, the National Trust and later the Campaign to Protect Rural England, all of which played a role in the creation of the National Parks.

There were repeated campaigns for legislation to open up the countryside for recreation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but they had little success. By the First World War there was an increasing disconnect between the concept of the rural idyll and the practical barriers to enjoying it on the ground. This divide became even more apparent at the end of the war, when returning servicemen could not freely enjoy the landscapes for which they believed they had risked their lives. Discontent with the status quo began to spread.

In 1929 the new Labour prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, appointed a National Parks Committee to examine the feasibility of the concept. Chaired by Christopher Addison, then Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Agriculture and previously the first Minister of Health, the committee concluded that our most precious landscapes should be protected by a network of reserves, some focusing on nature conservation and others on enabling urban populations to visit the countryside. The Labour government was, however, shortlived and the deteriorating economic situation became the overriding focus of political debate. The proposals in Addison’s report were never realised, but it was nonetheless a vital step in developing the idea of National Parks at government level.

It was in this period that the movement, which until then had been largely focused on political lobbying, developed a second front – direct action on the ground.

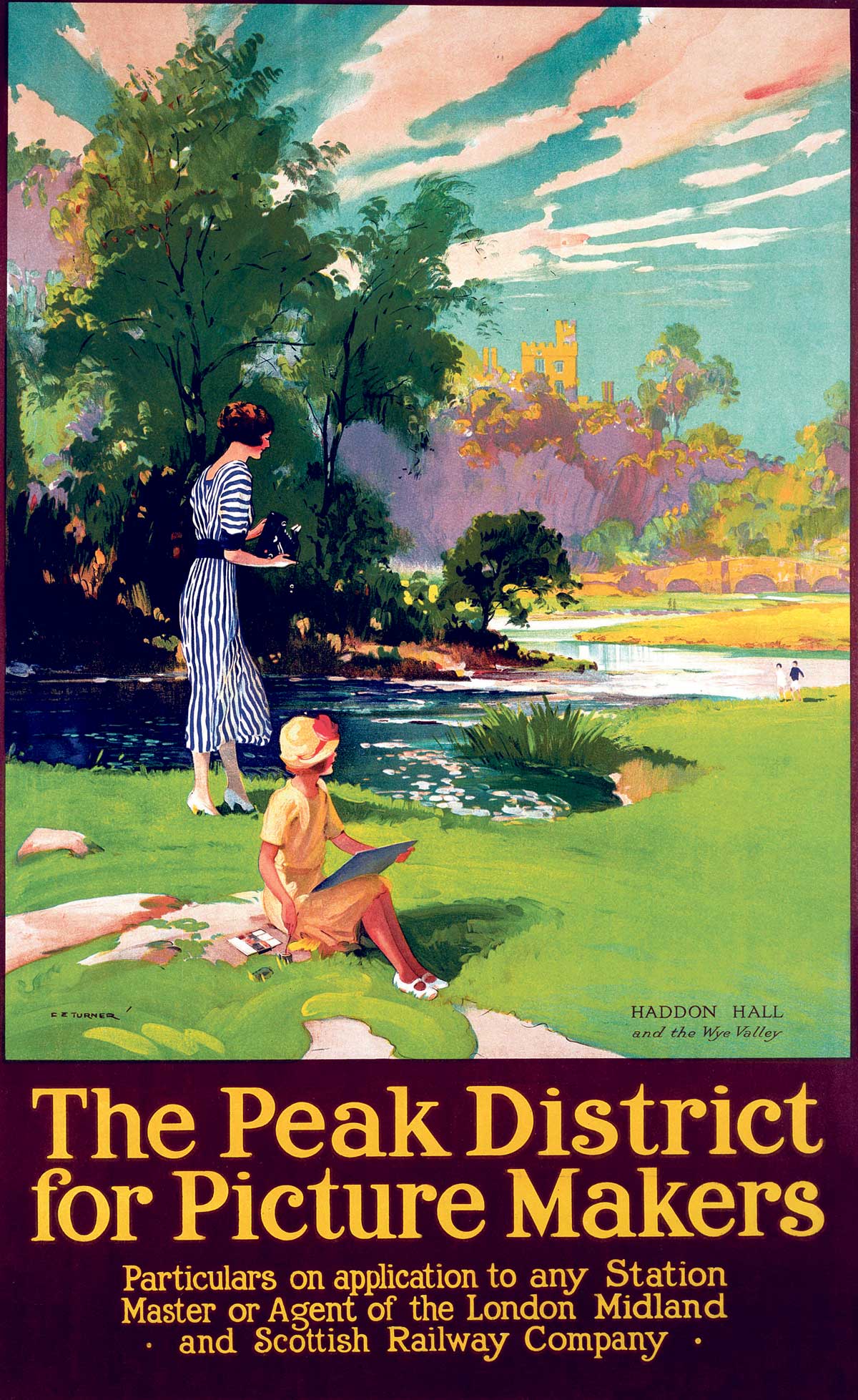

By the early 1930s, 50 per cent of the population of England lived within 50 miles of the Peak District, but over 60,000 acres of moorland were almost entirely closed to the public. Growing numbers of people began to walk on the land in protest but were turned back, so campaigners responded by organising a series of mass trespasses. The most famous took place on Kinder Scout in 1932 and brought new organisations to the cause, such as local workers’ clubs and the Young Communist League. Five of the protesters – who numbered about 400 in total – were arrested and imprisoned for six months on charges of riotous assembly and assault.

The outcomes achieved by the protest, however, were limited.

In 1936 the Standing Committee on National Parks was created to reignite the movement, which would later become the Campaign for National Parks. It focused on widening public support and brought together conservation and access organisations and also stressed the health benefits of spending time in the countryside. A key figure on the Standing Committee was John Dower, an architect and town planner who would later become a central figure in the creation of National Parks. He believed passionately that they were not just for the privileged or restricted groups, ‘but for all who come to refresh their minds and spirit, and exercise their bodies in a peaceful setting of natural beauty’.

Despite Dower’s efforts, it seemed that all momentum would be again be lost as the nation moved towards another global conflict.

In fact, however, the Second World War proved pivotal in building political support for the campaign. The coalition government was acutely aware of the need to ensure that plans were in place for postwar reconstruction and the concept of National Parks became part of this agenda. This interest in the countryside was certainly due, in part, to the view that agriculture was a vital national industry, but it extended beyond that to a wider concept of both landscape protection and popular access as part of a new social contract.

In 1941 Lord Reith, Minister of Works with responsibilities for postwar planning, appointed a commission on rural land use. The Scott Report, published the following year, made many recommendations, including that National Parks were long overdue and should be accessible to the public.

John Dower was then appointed by the government to set out proposals on how National Parks should be introduced and run. He was now working as a civil servant, but was suffering increasingly poor health from TB. His illness, which would ultimately result in his death in 1947, did not prevent him from continuing to drive his vision for the National Parks. Drawing on his extensive earlier work, Dower provided a comprehensive set of recommendations in his landmark report of 1945. They included that National Parks should combine both conservation and recreation; allow for established farming use to be maintained; and suggested ten areas for designation, including the Lake District, Snowdonia, Dartmoor and the Peak District and Dovedale.

The new Labour government remained committed to the principles of protecting these landscapes and allowing access to them. A further committee was appointed, chaired by Sir Arthur Hobhouse, to prepare the groundwork for the legislation, and the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Bill was introduced in Spring 1949. It was not without opposition, from landowners and local government, for example, and some of the original provisions were weakened, but the core objectives were achieved.

Introducing the bill in the House of Commons, Lewis Silkin, the Minister for Town and Country Planning, described it as ‘a people’s charter for the open air’, which would enable people to make the countryside ‘their own’. Seventy years on it remains a remarkable legacy of postwar ambition.

Corinne Pluchino is chief executive of the Campaign for National Parks (CNP).