It’s Not Easy Being Green - 5 minutes read

Moving away from petrol-powered vehicles is possible, as Brazil has proven. The country’s history of sugar-ethanol production provides both an inspiring vision of what a rapid shift away from petroleum might look like and a cautionary tale of the costs that come with it. Brazil’s investment in sugar-ethanol transformed an important domestic agricultural product into a national energy option, but it also produced extensive environmental and social costs that the country still struggles to address today.

Ethanol, or ethyl alcohol, can be distilled from any starchy agricultural product, such as potatoes, grapes, corn or sugar cane, which Brazil uses. The technology to use ethanol as a fuel has been around as long as the internal combustion engine. Early supporters included Henry Ford and Thomas Edison.

The Brazilian government began funding research on the possibilities of using ethanol in cars in the 1920s. As a country without large oil reserves, sugar-based ethanol presented an opportunity to create a domestic alternative and to ‘give a boost to our sugar industry’, as President Epitácio Pessoa noted in 1922. Brazilian researchers found that ethanol mixed with petrol fuel at up to 25 per cent without having to adjust existing petrol-powered engines. In 1931, therefore, the government mandated a five per cent mixture of ethanol in the national car fuel supply.

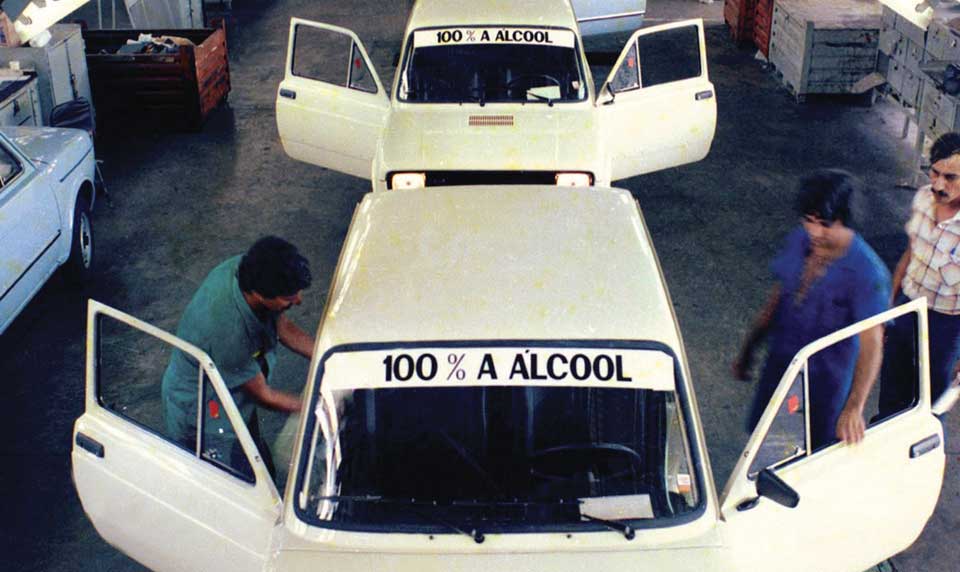

Still, it was not until the 1973 world oil crisis that the government put a larger emphasis on ethanol. In 1975 the military government created the National Ethanol Program (Proálcool), which used incentives and mandates to overhaul the nation’s fuel infrastructure. In addition to heavy investment in sugar production and distilleries, the programme launched domestically developed ethanol-fuelled cars in 1979. With the help of extensive subsidies they quickly dominated the market, representing 95 per cent of all new cars sold in the country by 1985.

However, ethanol’s ascendance came with significant environmental and social repercussions. Over the course of its first decade Proálcool would expand ethanol production from a little over half a billion litres of ethanol per year in 1975 to three billion litres a year in 1979 and over ten billion litres in 1985. Such a rapid expansion brought a dramatic transformation of the countryside. Sugar production was the cause of extensive deforestation in the sugar-producing state of São Paulo. Sugar cane pushed into other regions as agro-industrial production expanded.

Ethanol production also created an additional byproduct, vinasse, which turned sugar-ethanol production into one of the country’s most polluting industries of the late 20th century. A highly acidic liquid, vinasse is produced at a rate of ten to 16 litres for every litre of ethanol. Producers disposed of it in waterways, creating algae blooms that destroyed flora and fauna, deteriorated drinking water quality and increased public health risks. Public outrage pushed government regulation to reduce vinasse dumping in the 1950s, but producers often did not comply because it was cheaper to dump it in local waterways. Continued problems with vinasse-dumping marred the sugar-ethanol industry’s environmental image, even as specialists encouraged repurposing the nitrogen-heavy byproduct as a fertiliser. Today, compliance with anti-dumping legislation is still not effectively enforced.

At the same time, expanding sugar production relied on exploitative labour practices that connected sugar to Brazil’s colonial past; sugar cane had powered colonial Brazil’s slave-driven economy for centuries. In the 1970s and 1980s the industry’s growth required an influx of hundreds of thousands of mostly temporary labourers to work the expanding sugar fields. They worked in notoriously exploitative conditions, with poor pay and often living in what the São Paulo Agricultural Workers’ Federation called ‘modern slave quarters’. Workers have had to fight for basic labour rights, even as sugar production aggressively expanded to accommodate ethanol car-drivers in largely urban centres across the country.

Brazilian ethanol gained its image as a ‘green’ alternative to petroleum in the 1980s and 1990s. In the mid-1980s, research on the impact of ethanol-fuelled cars on air quality in Brazilian cities found that on average ethanol cars released significantly lower carbon emissions than petrol cars. Thereafter, ethanol’s environmental benefits were promoted. ‘With the ethanol car, you help depollute the air in your city’, one advertisement claimed. Proálcool was also presented ‘as a helpful model for preserving the environment’ and a ‘unique program that worked’. Successfully emphasising ethanol’s lower carbon emissions silenced its complicated history of pollution and exploitation.

This new green framing sustained domestic support and garnered international interest into the 21st century. Even though ethanol cars lost the Brazilian market in the 1990s, the launch of flex-fuel cars, which run on any mixture of ethanol and petrol, again revolutionised the country’s car market and solidified ethanol’s place in its fuel infrastructure in the 2000s. Today flex fuel cars dominate Brazilian roads and the country has one of the most diverse energy infrastructures in the world. Governmental campaign slogans continue to promote ‘Brasil: País da energia limpa!’ (Brazil: Country of clean energy!) and the 2017 RenovaBio programme seeks to meet Brazil’s commitments under the 2012 Paris Climate Accords largely through the use of ethanol in the transport sector. Yet, such ethanol-fuelled optimism ignores how land change linked to agro-industrial growth and the decimation of the Amazon rainforest have made Brazil the sixth largest greenhouse gas emitting country in the world.

As the world searches for alternatives to petroleum-based fuel, Brazil’s continued commitment to ethanol inspires hope that low carbon futures are possible. The Brazilian ethanol industry now represents more than 15 per cent of the country’s annual energy consumption. However, understanding the historical costs that came with this reminds us that low carbon options, too, will bring their own issues in the future.

Jennifer Eaglin is Assistant Professor of environmental history/sustainability at Ohio State University and the author of Sweet Fuel: A Political and Environmental History of Brazilian Ethanol (Oxford University Press, 2022).

Source: History Today Feed