The Man Who Walked His Life Away - 27 minutes read

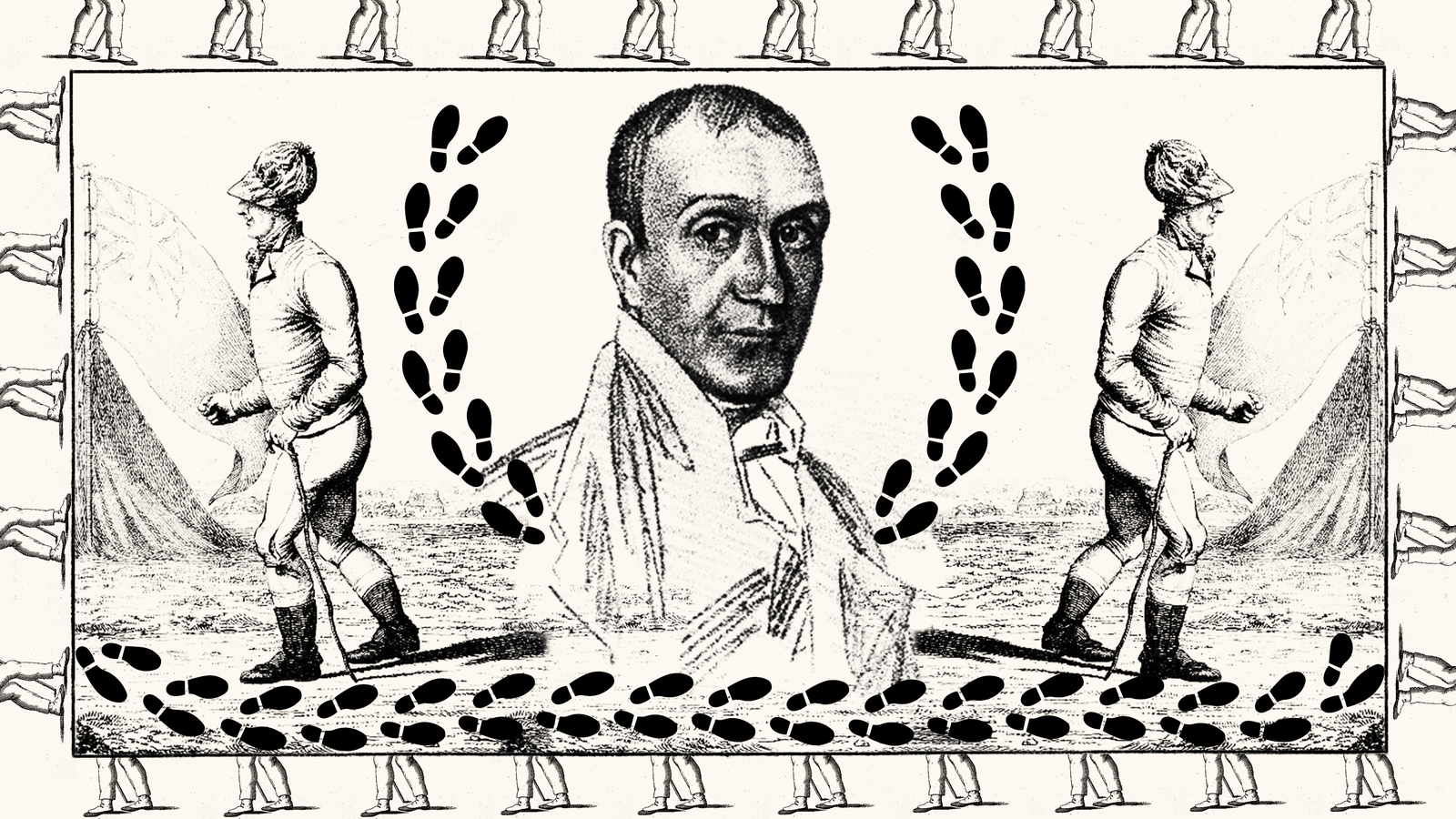

George Wilson, The Man Who Walked His Life Away

George Wilson, The Man Who Walked His Life AwayGeorge Wilson stepped out into the medieval-walled prison yard and began to walk. He was 47 years old, beaten-down, and half-starved. His squat frame and stubby legs hardly suggested athletic excellence. But Wilson was well-known as a perambulator, a peregrinator, and a master of “leg-ology.” He was a celebrated competitive walker and a champion in the bizarre sport of pedestrianism.

It was April 16, 1813, and Wilson was in prison for his failure to pay a debt of 40 pounds owed to his brother—in 2019 terms, roughly $3,200 USD. The fantastically grim Newgate Jail, in Wilson’s hometown of Newcastle upon Tyne in the north east of England, had originally been a fortified gate tower in the ancient town wall—an eight-foot-thick defense built in the early 13th century to protect from attack by Scottish invaders. By the time Wilson arrived, Newgate was 600 years old, and its battlements and arrow slits were no longer in use. Wilson was one of around 40 prisoners shoved into six cramped stone rooms with no heating, no sanitation, and not enough beds.

Penniless and shunned by his family, Wilson carried out menial tasks for his fellow prisoners in exchange for food. He was forced to work for a gang that trafficked alcohol into the prison and was tormented and beaten by gang members and guards. “I believe I should ultimately have perished,” he wrote in his memoir, “but for an extraordinary incident in which my favorable practice of walking procured me a most reasonable relief.”

Wilson proposed, for a wager of three pounds and a shilling (around $250 in 2019), to walk 50 miles in 12 hours within the narrow confines of the prison yard. For his stake, Wilson pledged his only possession other than the ragged clothes on his back: his father’s watch, which he said he valued “almost as much as my life.” Wilson had been undertaking walking challenges for more than a decade, but never in such unusual circumstances. “This was a feat that appeared so utterly impracticable,” he wrote, “that my challenge was readily accepted.”

The small paved yard measured around 35 feet by 25 feet. One newspaper described it as “probably the smallest track on record.” Wilson would have to make 2,575 laps of the yard to complete the 50-mile challenge. With the other prisoners watching from the doorway, counting his every revolution, he walked with a shuffling gait along the inside of the walls, turning at each of the four corners to complete a lap.

He walked for an hour, then two, then five, then 10, punishing his feet as darkness fell. With an hour remaining, he had four and a half miles left to go, right about on pace. He kept walking, one step at a time, and hit 50 miles with four minutes and 43 seconds to spare. He had completed the challenge “to the great disappointment and wonder of my antagonists.”

News of Wilson’s feat soon breached the prison walls. It was reported with awe in newspapers in London, Manchester, and Edinburgh. The Sporting Magazine described it as “an effort of human strength in so circumscribed a situation as stands unparalleled in the records of pedestrianism.” Wilson—“the Newcastle Pedestrian”—was now famous across Britain and now had three pounds and a shilling in his pocket, but the relief that brought him was short-lived.

Wilson had in mind a much greater challenge over a much longer distance that would generate even wider fame. He would need to overcome a terrible, crippling injury. He would need to escape from poverty and free himself and his children from strangling debt. And he would have to walk farther than any pedestrian had ever gone before.

And before any of that, he would need to get out of the hands of the gang and out of jail. Wilson’s celebrity brought unwanted attention, and he was preyed upon by the gang boss who, Wilson said, forced him to become his “bedfellow”—a word that, in the early 19th century, had intimate connotations. Wilson served the boss for eight months and became a trusted aide. But when he refused to help extort other prisoners, he was stripped and beaten by a gang enforcer, who knocked him to the ground and smashed his face against the stone floor. Then he was seized by the prison guards and thrown, naked and bleeding, into a gruesome dungeon known as the Black Hole.

George Wilson was a shoemaker by trade, which was useful given the number of soles he would wear out over his career. He walked great distances long before walking became his profession. As a youngster, Wilson decided he wanted to be a policeman in London, so he walked 276 miles from Newcastle to London, presented himself at a police station, was told to go home, and walked 276 miles back.

He had been born on June 26, 1766, in and began his Newcastle life in relative prosperity as the son of eminent shipbuilder Robert Wilson. But his childhood lurched into Dickensian hardships after the shipbuilding business collapsed and his distraught father, according to Wilson, “died of a broken heart.” With the family mired in debt, Wilson was handed over to the charge of the Newcastle Corporation—the town’s local government—and was apprenticed to a cordwainer or leather shoemaker who, he said, treated him with “great unkindness and cruelty.”

After several years under the cordwainer’s heel, Wilson eventually earned his freedom. He continued to make shoes and began to trade in clothing and fabrics. The work required him to travel every couple of months to London. “As walking was always my favorite amusement,” he wrote, “my visits were always performed on foot.”

In 1795, Wilson married Isabella Tubman, a household servant. Over the next decade, the couple had six children. The pressures of raising a family saw Wilson seek various additional employments to increase his income. He worked as a pawnbroker, a courier for a law office, and a tax collector. “The want of industry never formed any part of my character,” he wrote.

The tax collector job gave him the enjoyment of walking 50 or 60 miles each day but saw him ostracized by the local community. He was jeered and hissed as he made his collection rounds and received the nickname “Dog-tax.” “The office of a tax-gatherer is not the most popular,” he noted. The 30-pounds-a-year wage “sweetened the bitterness of my duties,” but he eventually resigned and returned to his clothing business.

It was on one of his business trips to London in 1805 that Wilson met a mapmaker named John Cary. Impressed with Wilson’s walking, Cary invited him to help plot his maps and to sell them along the way. Cary offered Wilson a mechanical wheel called an ambulator to measure distances, but Wilson claimed to be able to measure accurately using only his stride: “I declined the trouble and embarrassment of pushing the wheel through a journey so extensive.”

Wilson traveled widely across Britain, making amendments and additions to Cary’s maps before returning to London for his next assignment. He was accompanied on many of his journeys by his faithful dog, Rosa, a cross between a Newfoundland and a British mastiff. “She was of very large size, great strength, and inviolable fidelity to me,” wrote Wilson, “and more than once saved my life.”

One of those occasions occurred in the craggy landscapes of the Scottish Highlands. After negotiating Loch Ness and the Moray Firth, Wilson decided to climb Ben Nevis, Britain’s highest mountain. As he neared the peak, a dense fog descended, and he was saved from stumbling over a 200-foot precipice only by Rosa’s barked warning. Man and dog huddled on the freezing cliff-edge overnight, “trembling with horror,” before carefully descending in the morning light.

Wilson regularly completed his walking assignments “in little more than half the time expected,” he claimed. “I found as my exertions advanced that my fatigue decreased, and my strength and agility were rather improved than exhausted. He had a conspicuous talent for walking long distances and had found an opportunity to make it pay. Believing his wife and children could successfully maintain his clothing business, he decided to keep on walking and turn his pastime into a profession of its own.

Wilson was not a typical athlete, by the standards of his or any other time. He was 5-foot-4 and weighed just over 120 pounds. He had short, bowed legs and small feet. His thighs were “awkwardly hung together,” and his arms were “rather disproportionately long.” He walked with a short, shuffling step. “In person, Wilson by no means had the appearance of a man capable of great muscular exertion,” said the Sporting Magazine. It was noted, however, that he had remarkable strength and stamina, and that he “seldom perspired.” He was an unusual sportsman, but pedestrianism was an unusual sport.

In Wilson’s time, the era of the Napoleonic Wars and the First Industrial Revolution, sporting popularity was on the rise, driven by an increasingly insatiable appetite for gambling. Wagers were placed on sporting feats “both sublime and ridiculous,” according to Montague Shearman’s history of the sport in the Victorian-era book Athletics and Football. “The more extraordinary the wager, the more excitement it often caused among the public.” His book records wagers placed on a challenge for an unnamed man to run seven miles in 45 minutes with 56 pounds of fish on his head. It also describes a race between a young man with a jockey strapped to his back and an elderly fat man without a rider, and then a race between a man on foot and a man on stilts. (The man on stilts won.)

Pedestrianism challenges were slightly less wacky if no less remarkable. Most were endurance challenges in which competitors walked great distances against the clock for a wager or a prize, often in front of tens of thousands of spectators. Others were more formal races or “matches” with multiple walkers competing around a track, again over long distances, usually until there was one competitor left standing.

The first celebrity pedestrian was Foster Powell, a law clerk by trade, who, in 1773, walked from London to York and back again, a distance of 396 miles, in six days for a wager of one hundred guineas. A guinea was a gold coin worth one pound and one shilling, and it would take the average worker more than five years to earn one hundred guineas. According to Shearman, Powell—or, perhaps more accurately, Powell’s winnings—“did much to spread the popularity of pedestrianism as a sport.”

Powell’s fame was eclipsed a few decades later by that of Robert Barclay Allardice, a captain in the British Army who became known as Captain Barclay. Barclay’s most remarkable feat of pedestrianism was the successful completion of one thousand miles in one thousand hours at Newmarket Racecourse in June 1809 for a wager of one thousand guineas (in 2019 terms, about $1.2 million). Taking only occasional rest breaks, Barclay walked an average of 24 miles every day for 42 consecutive days.

By the early 1800s, only bare-knuckle boxing could match pedestrianism for popularity. In 1811, Englishman Tom Cribb and American Tom Molineaux fought an epic “world championship” bout in front of 25,000 spectators for a prize purse of 600 guineas. Cribb, who was backed and trained by Captain Barclay, had been a coal porter and Molineaux was a former slave. Both became hugely wealthy. Sports offered a rare opportunity to climb out of poverty at a time of almost insurmountable social inequality.

Wilson said he would have liked to have been a boxer if his “ill stars” had not prevented him. Instead, he was driven to achieve the fame and earnings of a professional pedestrian. “Most men have an ambition to be thought excellent in some pursuit,” he wrote. “Walking was the object of my emulation. I anticipated that it could open my road to celebrity and emolument. It was this spark that cheered me by day and lighted me by night in many a tedious journey, gave new spring to my sinews, and encouraged, perhaps, my vanity, to perseverance.”

Wilson’s first notable feat of pedestrianism was in 1805, at age 40, when he walked across England at its narrowest point—a distance of 84 miles in 22 and a half hours. He undertook high-profile challenges at Newmarket in 1807 and London in 1808. Then, in 1809, he walked 360 miles over six consecutive days for a prize of 50 guineas.

More than two hundred years later, the feats of Powell, Barclay, and Wilson seem relatively quaint when compared to the achievements of today’s athletes. (In the modern sport of race walking, the world record over 50km (31 miles) was set by Yohann Diniz in 2014 at just over three hours and 32 minutes.) Athletes are stronger and faster than they were two hundred years ago thanks to advances in training and technology and a better understanding of the capabilities of the human body. But Wilson and his fellow pedestrians can’t be measured by modern standards.

“Given exactly the same task, a modern-day athlete would find it almost impossible to accomplish what George Wilson and the ultra-tough 19th-century pedestrians managed,” says Paul S. Marshall, a historian of pedestrianism and the curator of the website www.kingofthepeds.com. “By ‘exactly the same task,’ I mean replicating as much as possible the same conditions. That would mean eating the same food and wearing the same footwear and clothes.”

Wilson ate boiled chicken and eggs and drank tea and “a moderate quantity of Madeira wine.” He wore a cotton shirt and trousers, gaiters over his handmade shoes, and a straw hat on his head. He walked every single day, for pedestrian challenges, for his mapmaking work, and to satisfy an elemental need to keep moving. “The profession of walking is not altogether a matter of choice,” he explained.

In 1812, after several months away and thousands of miles walked, Wilson returned to Newcastle. His children were pleased to see him, but his wife was not. “I found her reception of me cold, and her affections quite estranged from me.” Wilson shortly deduced that Isabella was having an affair with someone who was very close to him, perhaps his brother. He accused his wife of having neglected the family and business—despite having himself been away from both for the greater parts of several years.

Then he lost Rosa. His beloved dog had walked alongside him for a decade, but had been worn out “to almost a skeleton.” Rosa died of exhaustion, “and thus left me to lament the loss of the most truly faithful and unchangeable friend I ever had.”

Isabella convinced Wilson’s “deluded” brother to have him arrested for the debt of £40, and he was thrown into Newgate. This betrayal, he said, was “a wound in my heart deeper, if possible, than all I had previously suffered.” His brother did eventually show a degree of mercy, after hearing of his incarceration in the Black Hole, by arranging for Wilson’s release—subject to a payment of £10 to write off the debt. A friend made the payment, and Wilson went home. But his ordeal was not over.

According to Wilson, Isabella’s betrayals had become “so flagitiously infamous” that the couple constantly argued, often violently. On one occasion, Wilson wrote, he was so “maddened by her infidelities” that he struck his wife. Isabella, “a robust woman,” grabbed him by the throat and pinned him to the floor. Then their oldest son, 17-year-old George Jr., took a red-hot poker from the fire and struck Wilson with it several times.

Dreadfully injured, Wilson was arrested and thrown back into jail. He had terrible wounds to his left leg, which the prison doctor considered amputating. The leg was eventually saved but Wilson, the professional pedestrian, would walk with a limp for the rest of his life.

Wilson left Newcastle on a bitterly cold morning in February 1814 with only the clothes on his back and two shillings and nine pence in his pocket. It had taken him several months to recover from his injuries, after which he borrowed money to bail himself out of jail. Aware that Isabella was seeking to have him imprisoned for life, Wilson walked to London, but this time didn’t make the round trip. In London he resumed his paid-for pedestrianism, walking 96 miles in 24 hours for 30 pounds, and used the money “to pay my debts and to fulfill the duties of a father.” Then came his greatest challenge.

Captain Barclay’s 1809 achievement of walking one thousand miles in one thousand hours remained the greatest feat of pedestrianism and had not been topped in six years, despite several attempts. Wilson decided he would not only better Barclay’s achievement; he would batter it. He would walk one thousand miles in less than half the time it took Barclay – in just 480 hours, or 20 days. He would do so for the relatively modest prize of one hundred pounds, although he hoped wagers and subscriptions from benefactors might substantially increase his purse.

Handbills were distributed all over London:

Blackheath is an area of grassland, about half a mile across, in south-east London. Wilson set off from the Hare and Billet pub on the corner of the heath. He walked circular laps between markers, clocking up a mile every time he passed back by the pub. He walked 50 miles on the first day “without appearing the least fatigued.” “If God spares my health, and barring all accidents,” Wilson told journalists, “I am sure I shall complete my task.”

Bookmakers were less sure, offering odds of 20 to 1. And the task became more difficult on subsequent days, partly due to unusually hot and dusty conditions and partly due to a growing crowd of onlookers, which swelled in size from hundreds to thousands and began to obstruct his way.

Some obstructions were accidental, and some were deliberate. Gamblers had bet up to one thousand guineas on Wilson to fail, and some of them took direct action to ensure that happened. One man kneeled on Wilson’s foot while pretending to tie his shoelaces, and also put pebbles in his socks. Another individual ran at Wilson and kicked him in the back, knocking him to the ground. Wilson got up and thumped his assailant before being restrained.

One evening Wilson was approached by two men who offered him one hundred guineas to throw the challenge. “I would sooner lose my right hand and see it consumed in a fire than accede to such a measure,” he told them. On another occasion, he was handed a drink that turned his stomach and was found to contain poison of the kind used to incapacitate racehorses. He was prescribed a remedy by a doctor and advised not to accept any further food or drink from strangers.

On the 10th day, he reached the halfway point, 500 miles. By now the crowd was becoming so disruptive that Wilson’s supporters walked alongside him carrying poles and driving whips to clear the way. “Perhaps on no public occasion did there congregate on one spot so numerous an assemblage of all descriptions,” wrote one reporter. “They were in fact literally beyond calculation, and harmlessly happy.” The press christened Wilson with a new moniker that would stick with him for the rest of his life. “The Newcastle Pedestrian” became “The Blackheath Pedestrian.”

By the 12th day, with no signs of his flagging, the odds on Wilson completing the challenge had fallen to even. The heath now resembled a carnival. Colorful tents and booths were erected all over its surface, offering alcohol and entertainments including “tumblers, rope-dancers, fire-eaters, and conjurers.” There were theater and music tents, two brothels, and two menageries. A large elephant stood outside the Hare and Billet and roared “most conscientiously” every time Wilson completed a mile. Several portrait artists turned up to capture Wilson’s fame. Printing presses were set up on the heath and “a very fair likeness” could be obtained for three pennies.

This hubbub inevitably attracted the attention of local lawmakers. Magistrates ordered the closure of many of the booths, primarily those selling alcohol. Then the magistrates came for Wilson. On the morning of the 16th day, having walked 751 miles, Wilson was arrested by a “posse” carrying a warrant stating that the pedestrian was “occasioning a considerable interruption to the peace of the inhabitants.”

Wilson’s friends were outraged. He received hundreds of letters of support, and newspapers condemned his treatment. He stated that he hoped to complete the challenge as soon as the magistrates’ court cleared him. But the court appearance was delayed beyond the 20th day. Wilson’s attempt had failed. “I must only declare that my failure does not arise from any want of physical strength,” he said. A doctor who was called to assess Wilson’s heath added, “I do not doubt he would have accomplished his task, had he been permitted.”

Five days later, Wilson appeared in court. In remarkable scenes, it was revealed that a corrupt magistrate, John Rice Williams, had falsified the warrant for Wilson’s arrest, perhaps under the influence of a gambler. The charges were immediately dropped, and Wilson was discharged. “The pedestrian was then conducted home in triumph,” reported the Morning Chronicle, “decorated with ribbons, and accompanied with the shouts of the multitude.”

Wilson made a special appearance outside the Hare and Billet. He walked a lap of the heath, surrounded by cheering supporters, and was serenaded with a newly-written song, “Looney’s Visit to Blackheath”:

Wilson took to the stage and made a speech, prefaced by the warning that “walking and not talking is my trade.” He thanked the crowd and told them he would continue to walk to earn money to support his family. He would “rise like the sun from an eclipse or the gloomy envelope of a cloud to shine with renovated splendor.” The crowd cheered and threw coins onto the stage. The coins, to Wilson’s disappointment, came to the value of just four pounds.

He was still at Blackheath when he wrote his memoir. Its remarkable full title was: A Sketch of the Life of George Wilson, the Blackheath Pedestrian; Who Undertook to Walk One Thousand Miles in Twenty Days!! (But Was Interrupted by a Warrant From Certain Magistrates of the District, on the Morning of the Sixteenth Day, Having Completed 750 Miles.) The book—really an 80-page pamphlet—was partly an attempt to highlight the corruption that had halted his challenge, but also an effort to capitalize on his growing fame.

The controversial end to the challenge only increased public interest and caused Wilson’s fame to cross the Atlantic. The Times of London, Britain’s newspaper of record which generally ignored sporting news, had provided daily updates on Wilson’s progress. After the arrest, the Times reported that “the New York newspapers” were also covering the affair. He had achieved the celebrity he desired, if not the “emolument” he needed. Wilson had found fame through failure.

In October 1816, 12 months after Blackheath, George Wilson stood in the walled garden of the Ship Launch Inn, in Hull, Yorkshire. He had, as promised, continued to walk—50 miles in under 12 hours in Norwich, one hundred miles in 24 hours in Yarmouth, 250 miles in five days in King’s Lynn. But Wilson had not forgotten his failure at Blackheath, and now he intended to complete the thousand-mile challenge even quicker than he had previously attempted. In the pub garden in Hull, he would walk one thousand miles in just 18 days.

He had chosen a private garden so he wouldn’t be obstructed—or arrested—but Wilson was still watched by a crowd of onlookers who paid for admission, or who had scaled the walls and climbed through hedges. On he went, clocking up more than 55 miles each day. On the 18th day, as he walked his one-thousandth mile, a band played Handel’s “See, the Conqu’ring Hero Comes.” Wilson completed the greatest challenge pedestrianism had ever seen with 40 minutes and 50 seconds to spare, “amidst the cheers of the populace.” He had finally eclipsed Barclay and become the greatest pedestrian the world had ever seen.

Unfortunately, Wilson was once again short-changed. He complained that the prize fund raised for the challenge was barely sufficient to pay his expenses. “This is very fortunate for the public,” noted the Northampton Mercury, “as it will tend to put an end to such exhibitions. If every idle fellow who chooses to take an extraordinarily long walk is to be paid for his trouble, there would be no end of such useless exertions, nor of the evils they bring to the indolent and thoughtless who lose their time in witnessing them.”

But Wilson continued to walk, accepting new challenges every few months all around Britain, selling his book and newly-printed postcards bearing his portrait as he went. He repeated his greatest feat by walking one thousand miles in 18 days in Manchester in 1817 and did it a third time in Chelsea in 1820. By then, he was 54 years old, and he declared he would not attempt it again, “having accomplished so many extensive and arduous undertakings.”

Wilson was bowing out before the golden age of pedestrianism really got going and before several of the sport’s biggest stars were born. Pedestrianism became an international phenomenon in the late-1860s and 1870s when British peregrinators such as Charlie Rowell and George Hazael faced off against American perambulators like Edward Payson Weston and Dan O’Leary for prize belts at the Royal Agricultural Hall in London and the original Madison Square Garden in New York.

Before Wilson retired, he had a hometown swansong. He returned to Newcastle in 1822, walking 90 miles in 24 hours on the town’s racecourse in front of a crowd of up to 60,000 people. Afterward, he was carried into the town center, where “the bells greeted his achievement with several merry peals.”

But his return home forced him to face up to his past. In August 1823, he was arrested and convicted of being a “rogue and a vagabond” for abandoning his wife and children. He was sentenced to three months’ hard labor. Wilson may have been grateful for one small mercy: the dreaded Newgate Jail, condemned by prison reformers, had been demolished the previous month.

Still, Wilson wasn’t entirely done. In 1824, he walked 140 miles in 48 hours at Alston, Cumbria, despite reports he had “been lame in one of his legs for three months past.” His dedication to walking was catching up with him. “The circumstances of my life,” he noted, “have been chequered with vicissitudes that, long since, would have reconciled me to the fate which must, sooner or later, be the common lot of humanity.”

He died in 1839, aged 73, with the Newcastle Courant noting, understatedly, that Wilson was “well known in this town for his remarkable feats of pedestrianism.”

His fame was worldwide but short-lived. Pedestrianism proved a strange diversion that would soon be forgotten by the majority of the sporting world, and Wilson’s role in the craze was remembered by even fewer. In the days following the Blackheath challenge, Wilson’s toenails fell off and were donated to the British Museum in London. They were to be exhibited for posterity as a lasting monument of one of sports history’s most unusual characters. Unfortunately, having searched its collection more than 200 years later, the British Museum told me it can find no record of George Wilson’s toenails.

Paul Brown writes about sports history and lives in the north-east of England. His work can be found at www.stuffbypaulbrown.com.

Source: Deadspin.com

Powered by NewsAPI.org

Keywords:

George Wilson (baseball) • George Wilson (baseball) • Middle Ages • Squatting • Baby transport • -logy • Pedestrianism • United States dollar • Newgate Prison • Newcastle upon Tyne • North East England • City gate • Gate tower • Ancient history • Defensive wall • Scottish people • Newgate • Arrowslit • Sanitation • Poverty • Family • Domestic worker • Unfree labour • Alcoholism • Prison • Prison officer • Gambling • Shilling • Four Corners • One Step at a Time (song) • Great Disappointment • London • Manchester • Edinburgh • The Sporting Magazine • Pedestrianism • Newcastle upon Tyne • Shilling • Poverty • Trust (emotion) • Gang • Crime • BDSM • Black hole • Dennis the Menace (U.S. comics) • Shoemaking • Shoe • London • Newcastle upon Tyne • London • Newcastle upon Tyne • Shipbuilding • Robert Woodrow Wilson • Charles Dickens • Father • Family • Newcastle upon Tyne • Cordwainer • Leather • Shoemaking • Cordwainer • High-heeled footwear • Shoe • Clothing • Textile • London • Family • Pawnbroker • Dog • Tax collector • Wage • Duty (economics) • London • Cartography • John Cary • Map • Machine • London • Newfoundland (dog) • English Mastiff • Scottish Highlands • Loch Ness • Moray Firth • Ben Nevis • Mountain • Mountain • Fog • Cliff • Fatigue (medical) • Child • Business • Keep On Walking (Scouting for Girls song) • Foot • Genu varum • Foot • Thigh • Walking • Muscle • The Sporting Magazine • Physical strength • Endurance • Pedestrianism • Napoleonic Wars • Industrial Revolution • Gambling • Sublimation (psychology) • Montague Shearman • Sport • Victorian era • Sport • Football • Gambling • Gambling • Jockey • Old age • Fat Man • Equestrianism • Walking • Stilts • Pedestrianism • Gambling • Foster-Powell, Portland, Oregon • Law clerk • London • Guinea (coin) • Guinea (coin) • Gold coin • One pound (British coin) • Shilling • Guinea (coin) • Pedestrianism • Robert Barclay Allardice • British Army • Pedestrianism • Newmarket Racecourse • 1000 Guineas Stakes • Bare-knuckle boxing • Pedestrianism • Tom Cribb • Tom Molineaux • Guinea (coin) • Slavery • Poverty • Social inequality • Boxing • Remuneration • Pedestrianism • England • Newmarket Racecourse • London • Guinea (coin) • Racewalking • World record • Yohann Diniz • George Wilson (pitcher) • Pedestrianism • Shoe • Chicken • Egg as food • Tea • Madeira wine • Cotton • Shirt • Trousers • Gaiters • Shoe • Straw hat • Newcastle upon Tyne • Adultery • Family • Intimate relationship • Grief • Friendship • Black hole • Debt • Adultery • Kniphofia • Prison • Prison • Amputation • Newcastle upon Tyne • Shilling • Penny (British pre-decimal coin) • London • London • Pedestrianism • Pedestrianism • Blackheath, London • Grassland • East End of London • Hare and Billet • Pub • Gambling • 1000 Guineas Stakes • Direct action • Guinea (coin) • Stomach • Poison • Beyond Calculation • Newcastle upon Tyne • Blackheath, London • Carnival • Fire eating • Elephant • Hare and Billet • Arrest warrant • Magistrate • Doctor Who • Harold Wilson • Harold Wilson • Magistrate • John Rice (umpire) • Arrest warrant • Arrest • Driving under the influence • Gambling • The Morning Chronicle • Hare and Billet • Blackheath, London • Speech • Money • Family • Sun • Eclipse • Cornish Rebellion of 1497 • The Great Gatsby • Cornish Rebellion of 1497 • Pamphlet • The Times • Newspaper of record • Sporting News • Newspaper • New York (magazine) • Celebrity • Blackheath, London • The Great Gatsby • Walled garden • Pub • Kingston upon Hull • Norwich • Hundred (county division) • Great Yarmouth • King's Lynn • Harold Wilson • Blackheath, London • Kingston upon Hull • George Frideric Handel • Judas Maccabaeus (Handel) • Pedestrianism • Cheers • Northampton Mercury • Manchester • Chelsea, London • Before the Golden Age • Pedestrianism • Pedestrianism • Hazael • Edward Payson Weston • Dan O'Leary (American football) • Royal Agricultural Hall • London • Madison Square Garden • New York City • Newcastle upon Tyne • Vagrancy (people) • Penal labour • Newgate Prison • Prison • Alston, Cumbria • Pedestrianism • Pedestrianism • Blackheath, London • British Museum • London • British Museum • George Wilson (American football coach) • Paul Brown •