Classical Dinosaur | History Today - 4 minutes read

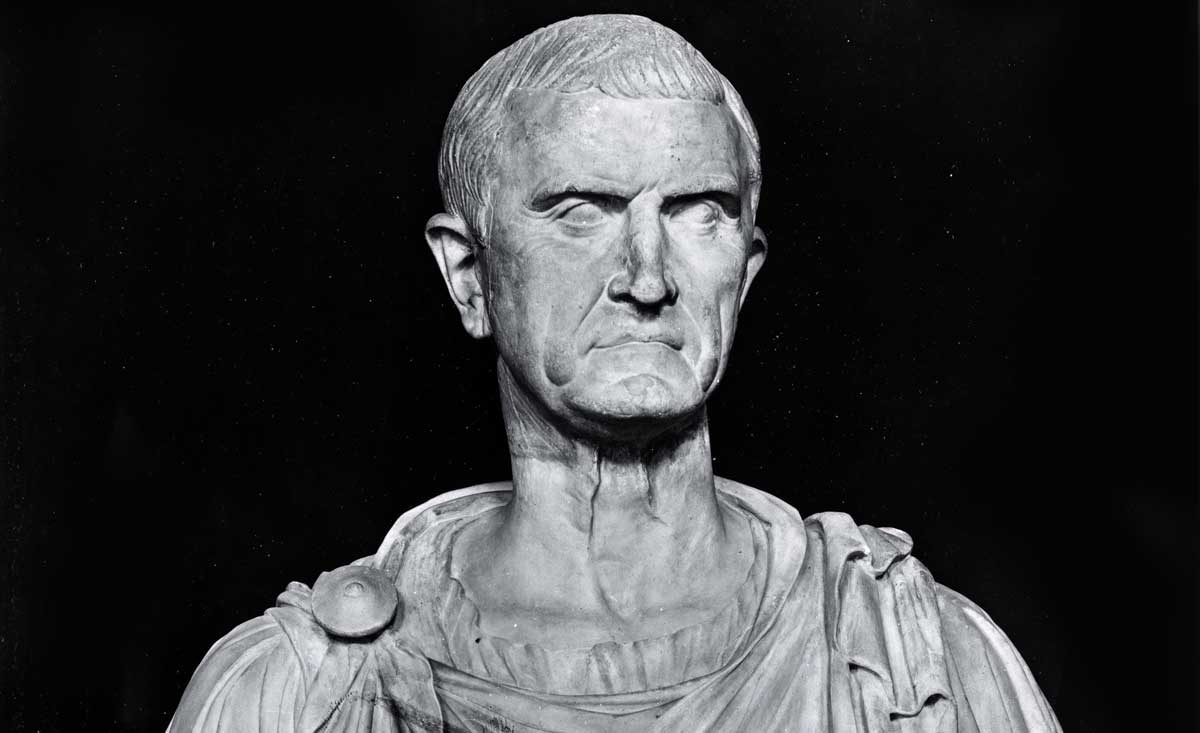

Shakespeare gave us an abiding image of Caesar. Pompey promoted himself as the second coming of Alexander the Great. But when it comes to the mysterious third man who pulled the strings and turned the gears of politics in first-century BC Rome, Marcus Licinius Crassus has only himself to blame for historical obscurity.

Eighteen years after rising to the public’s attention for ending Spartacus’ revolt, Caesar’s one-time banker and Rome’s former head of state departed for the Tigris and Euphrates with mad imperialist designs of annexing Parthia to Rome. An otherwise comfortable life of wealth and privilege ended with Crassus’ head being used as a prop on a Parthian stage. Peter Stothard profiles the life of this arrogant, ego-inflated, posh middle-aged Roman in Crassus, his slim, unapologetically top-down biography of Caesar and Pompey’s lesser-known but no-less-influential contemporary.

Stothard styles Crassus history’s ‘first tycoon’, but from the details of Crassus’ life, it’s hard not to regard him as an archetypal antihero and classical-era dinosaur: a real-estate mogul who acquired his wealth by profiting off collapsed tenements in Rome, a womaniser ‘accused of seducing a Vestal Virgin’ and a businessman who was particularly ‘innovative when understanding human capital’, so Stothard says, noting Crassus’ penchant for ‘buying and training the smartest of the enslaved’ to be his property managers. If historical writing has shifted attention from the privileged and powerful in recent years, hovering over the lives of outsiders and the disenfranchised, Crassus yanks that pendulum right from its socket.

There’s a reason why Crassus’ lifetime has perennially proven so seductive to both novelists’ imaginations and scholars’ scrutiny. Fraught with uncertainty over the citizenship status of local communities across the Italian peninsula – many of whom lived under Roman authority but lacked representation in Rome – and confronted by a list of domestic challenges resulting from the Republic’s acquisition of five new overseas provinces, the first half of the first century BC inaugurated a time of cut-throat competition and zealous partisanship from which would arise the Roman Empire.

What Stothard’s book offers is a quickly exposed snapshot of that changing world’s ‘clash of ego and ambition’ as it spiralled into dysfunction. Feeding the general mania of the times was the prospect of cartloads of stolen treasure from conquered provinces and dreams of skyrocketing personal wealth.

The broad thrust of the narrative is clear as Stothard leads us from Crassus’ youth, down ‘the road to Carrhae’, and to the national disaster that unfolded there in Parthia’s sands. Just don’t expect much help en route. You’ll need to do the sorting out of the politics of Marius and Sulla for yourself, to understand the roots of the conflict that led to Sulla’s attack at Rome’s Colline Gate in 82 BC. Narrative time will speed forward, then slip into reverse. Crassus is nearing 30, a partisan in Sulla’s march on the capital, when we encounter mention of a battle in Gaul during his childhood, 24 years earlier. Of Crassus’ intriguing contemporaries, like the wealthy, free-born Roman women whose backroom strategies helped them to support their cash-strapped husbands during these unusual years in the late Republic, we hear very little.

‘Men should learn from experience, respect their elders, and rise to the top in due time’, Stothard writes, attempting to convey to a 21st-century mind the ubiquity, if not the oppressiveness, of the paternalistic ideology that informed Crassus’ world. The first ancient writer to try to recover those lives and times was the imperial biographer Plutarch, and Stothard’s structure has largely followed Plutarch’s model: the first half of his book focusing on the formation of Crassus’ character, the second an extended set piece in the desert, replete with discussions of Parthian archery tactics, culminating in the doomed general’s defeat.

Stothard leans heavily into his subject’s qualities as a sort of management consultant and financial wizard just as, in a way, did Plutarch, whose Crassus was said to be ‘more like a businessman than a general’, even on the battlefield. Stothard calls Crassus a ‘meticulous planner’, ‘a secret disrupter’, a man who ‘prided himself on understanding risk’ and who exercised ‘power through money’ until the ill-planned Parthian invasion of 53 BC saw it all wiped out.

When he arrived in Parthia shortly before he died, says Plutarch, there was ‘not a single growing thing in sight, not a stream, not a sign of any rising ground, not a blade of grass. There was a sea of sand and nothing else’, a bleak end for a life-long narcissist whose greed wrought his own destruction.

Crassus: The First Tycoon

Peter Stothard

Yale University Press 184pp £18.99

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Douglas Boin is Professor of History at Saint Louis University and the author of Alaric the Goth (W.W. Norton, 2020).

Source: History Today Feed