The Body as Machine | History Today - 3 minutes read

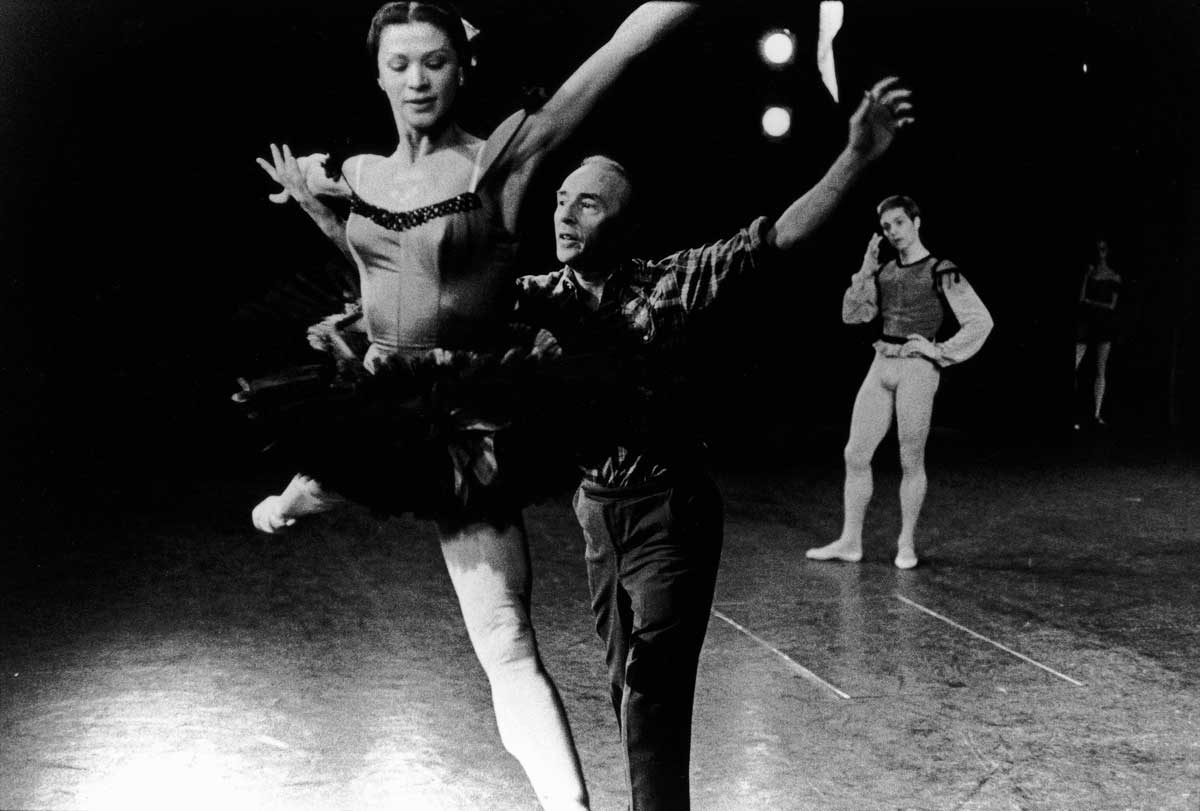

George Balanchine, founder of the New York City Ballet (NYCB), pursued pure abstraction in his choreography, emphasising the physical virtuosity of his dancers by foregoing narrative and theatrics. Jennifer Homans explores the man behind this quintessential American ballet aesthetic. For Homans, Balanchine considered the dancers’ bodies ‘his tools and his livelihood’, both machines and artistic material. With this rigour, she argues, his dancers could transcend worldly reality and become fully abstract.

But the offstage story reveals that Balanchine’s abstraction stemmed from his personal difficulties regarding politics, sickness, race and sex. For instance, citing ‘the anti-Communist, anti-Soviet, pro-liberal American impulse behind everything he did’, Homans describes how Balanchine used dance to distance himself from his traumatic youth during the Russian Revolution. Abstraction, then, was not solely about aesthetics, but also enabled Balanchine to claim an American identity and eschew his Russian artistic heritage. Abstraction also allowed Balanchine to cope with numerous physical ailments and the sicknesses of those around him. Agon (1957) – his most physically demanding work, pushing the body to the extremes of exhaustion – was created following a series of health crises among his closest collaborators. Homans describes Agon as a ‘dance about dancing, and nothing else’, but the work’s physical intensity corresponded to Balanchine’s preoccupation with the diseased body.

Agon’s deliberate interracial casting of Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams in the lead duet demonstrates that Balanchine was willing to infuse political elements into his abstract pieces. Still, Balanchine was not progressive in regards to race. Homans notes his failure to fully integrate the NYCB and his tendency to cast Black dancers in exoticised roles. He viewed colour as an aesthetic concern: ‘Skin was costume.’ On the longstanding debate regarding Balanchine’s use of African American dance elements, Homans briefly acknowledges that the choreographer ‘did more than borrow’ from Black dance traditions.

Mr. B also reveals how Balanchine’s abstraction was predicated on his lust for the female form. Homans is clear that Balanchine ‘needed to be physically attracted to a dancer’ in order to choreograph and believed that ‘only a man who loves women’ could lead the NYCB. Balanchine pursued his female dancers romantically and sought to control their bodies. His treatment of the body-as-machine led to eating disorders among the dancers, as fat ‘got in the way of seeing’ the abstracted body. These stories are troubling and merit a more robust critique than Homans gives, as they underscore the physical and personal costs of a career in Balanchine’s company.

In the introduction to Mr. B, Homans writes that ‘the suffering, the grit and hardship of everyday life, never once appeared in Balanchine’s dances’. Yet several of Balanchine’s worldly concerns did manifest in his abstract style. Having trained at the School of American Ballet, Homans cherishes her experience in the ‘unreal world’ of Balanchine’s choreography and argues for his transcendence and genius ability. Still, the intimacy of her biography displays the choreographer’s full humanity, including the very difficulties that he sought to transcend. Balanchine’s signature abstraction was conditioned by the challenges of his earthly life, and not even his artistic vision could supersede his human condition.

Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century

Jennifer Homans

Granta 784pp £35

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Emily Hawk is a PhD researcher at Columbia University, researching 20th-century dance.

Source: History Today Feed