How Not to Prepare for Nuclear War - 6 minutes read

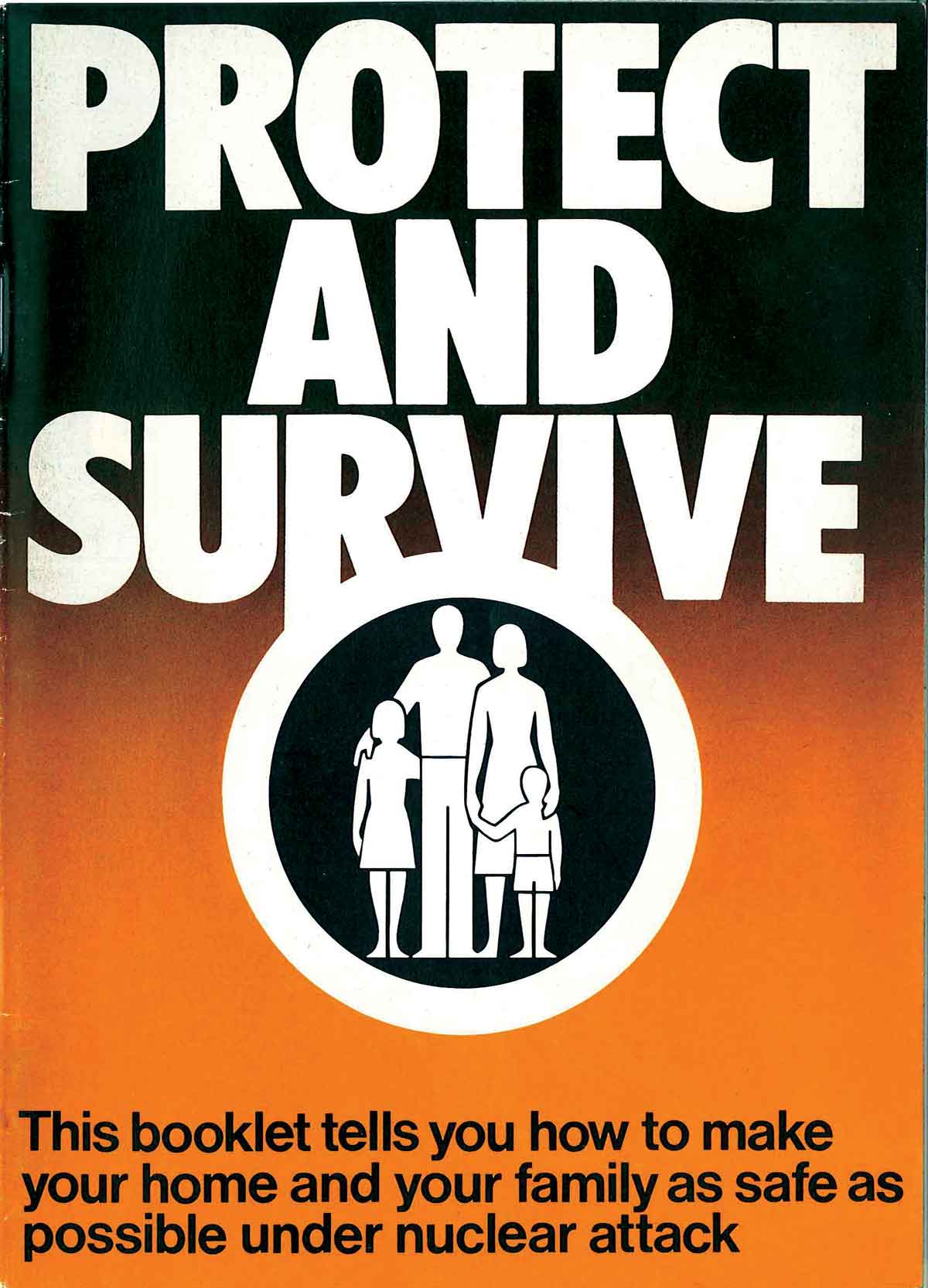

This year marks the 40th anniversary of Protect and Survive, the UK Home Office’s guide to surviving nuclear attack, being made available to the public. The embodiment of a government communications campaign gone wrong, the booklet has become a grim touchstone of British nuclear culture. Between its orange covers lay advice on ‘how to make your home and family as safe as possible’ should the unthinkable happen.

Householders were shown how to build a lean-to refuge using household items such as doors, suitcases and cushions – the end result more closely resembling a children’s sofa den than a sturdy fallout shelter. They were also instructed to whitewash their windows – in order to deflect the deadly nuclear heat flash – and to improvise a toilet from a chair and a bucket.

Today, much of the advice in Protect and Survive reads as, at best, an ineffectual charade and, at worst, a diversionary tactic to distract panicked citizens during a crisis. It was, though, never intended to be issued as a stand-alone booklet – in fact, it was never meant to be revealed to the public during peacetime at all.

Frequently associated with the heightened nuclear tensions of the early 1980s and credited erroneously to the first Thatcher administration, Protect and Survive actually originated under Harold Wilson’s Labour government. In late 1974, civil servants identified a need to replace the existing public guidance on the nuclear threat. More than a decade old at this point, 1963’s clunkily titled Advising the Householder on Protection against Nuclear Attack was out of date and out of favour. The Home Office sought to take full advantage of modern technology to inform the public: they planned a new campaign led by radio announcements and animated television spots, with a supporting booklet.

Unlike earlier campaigns, this was not designed to be publicised immediately. Instead, the first the public would know of it would be during a crisis, when the TV and radio recordings would start impinging on normal broadcast schedules, being accompanied eventually by the distribution of the booklet. Following a year of design, development and extensive market research to test its effectiveness, the Central Office of Information (CoI) – the government’s in-house advertising agency – completed production of the new nuclear advice at the end of 1975. A series of films premiered to an internal audience at the CoI’s private cinema and 2,000 copies of the accompanying booklet were posted to senior officials in the emergency services and chief executives of local authorities. While this limited distribution suggests an attempt to keep it under wraps, Home Office correspondence instead shows that there was no budget left to sustain the project further.

For a while, that was that: Protect and Survive was prepared, ready and waiting should an impending nuclear war demand its release. It remained largely unknown outside those who had a need to know. But international events in the closing years of the 1970s led to the breakdown of détente, rising nuclear anxiety and a renewed interest in Britain’s civil defence plans. In January 1980, The Times published a series of articles about the state of British preparedness, one of which included a photo of the Protect and Survive booklet. This was followed by clips from the films being broadcast on the BBC’s prime-time investigative documentary strand Panorama. Public outcry forced the government to hastily prepare a new version of the booklet for publication, which was soon made available for purchase for 50 pence.

Separated from the broadcast media it was designed to support, and released outside of the conditions for which it had been created – the tension and panic of inevitable nuclear attack – the Protect and Survive booklet seemed laughable and worthless, and critics gave it no quarter. Parodies, which tore its message to shreds, appropriated the Home Office’s words and illustrations. The team behind the UK edition of MAD Magazine created a satirical lookalike, Meet Mr Bomb. Described as ‘a practical guide to nuclear extinction’, it suggested survivors look on the bright side: after nuclear attack, they could enjoy riding mutant cockroaches the size of Shetland ponies. Peace campaigner E.P. Thompson’s Protest and Survive parodied the look, too, but coupled it with a more serious message against civil defence. The artist Raymond Briggs made a powerful graphic novel, When the Wind Blows, which told the tragic story of an elderly couple trying to follow the booklet’s instructions. The government advice was further sent up by comedians, including on sitcoms The Young Ones and Only Fools and Horses.

This cultural backlash impacted on the way subsequent government emergency preparedness campaigns were disseminated. The follow-up campaign, 1986’s Civil Protection, was aimed at emergency planners rather than the general public. It depicted various potential large-scale calamities such as industrial accidents and natural disasters alongside nuclear attack; almost certainly by design, the campaign completely failed to enter the public consciousness.

How would a similar booklet go down in 21st-century Britain? The UK’s most recent flirtation with this kind of public information – 2004’s Preparing for Emergencies – was unimpressive. A response to the growing threat of terrorism, the campaign was led by a booklet and supported by a website and broadcast ads. Unlike previous campaigns, the government printed and distributed the booklet to every household in the country. Despite this, it is hard to find anyone who remembers it, let alone the advice it contained. More recently, American-style advice issued in 2019 by police forces’ social media accounts on preparing a ‘grab-and-go bag’ was widely ridiculed. The same advice had been issued (and ignored) for years as part of an annual ‘Preparedness Month’ initiative. But tensions around an impending Brexit deadline led to it briefly becoming the centre of a social media frenzy – and to allegations of deliberate scaremongering.

Perhaps the Home Secretary Douglas Hurd was right when he said in 1986: ‘If new material was issued now, everyone would throw it into the wastepaper basket or make fun of it as they did with Protect and Survive; I don’t think there’s a sensible purpose in it.’

Taras Young is the author of Nuclear War in the UK (Four Corners Books, 2019).