Native America: A New Narrative? - 6 minutes read

David Treuer’s new book reaches the reader garlanded in praise from the world’s most revered arbiters of taste. It is a New York Times bestseller; the paper admires the way it ‘suggests the need for soul-searching’. Vanity Fair likes its ‘hopeful vision of the past and future of Native Americans’. The Economist calls it ‘sweeping, essential history’. Books on Native American history are often ignored. Why is this one different?

One reason is that it is not an examination of the colonial roots of Native disadvantage. Instead, it is a good news story about Indian resurgence told by an American literary star, an Ojibwe from Leech Lake Reservation in northern Minnesota. It is no coincidence that The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee is enjoying a similar level of mainstream approbation as J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis in 2016. Yale-educated Vance told a story of how boot-straps dedication to hard work had allowed him to transcend the welfare-dependent culture of his Kentucky childhood. Vance’s message, that the real problem for poor white Appalachians is despair and learned helplessness rather than a structural lack of opportunity, proved so welcome in the Trump-era that a film adaptation is in production. Treuer’s book is not so personal, but his message is just as congenial to today’s small government and strong personal responsibility ethos. Rather than the old, popular story told in Dee Brown’s 1970 bestseller Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West – that America was responsible for tragic acts of cultural destruction against Native Americans – Treuer is keen to promote awareness that the Indian heart beats on. Indeed, it is doing better and better: ‘No longer does being Indian mean being hopelessly characterized as savage throwbacks living in squalor on the margins of society, suffering the abuses of a careless, unfeeling government.’

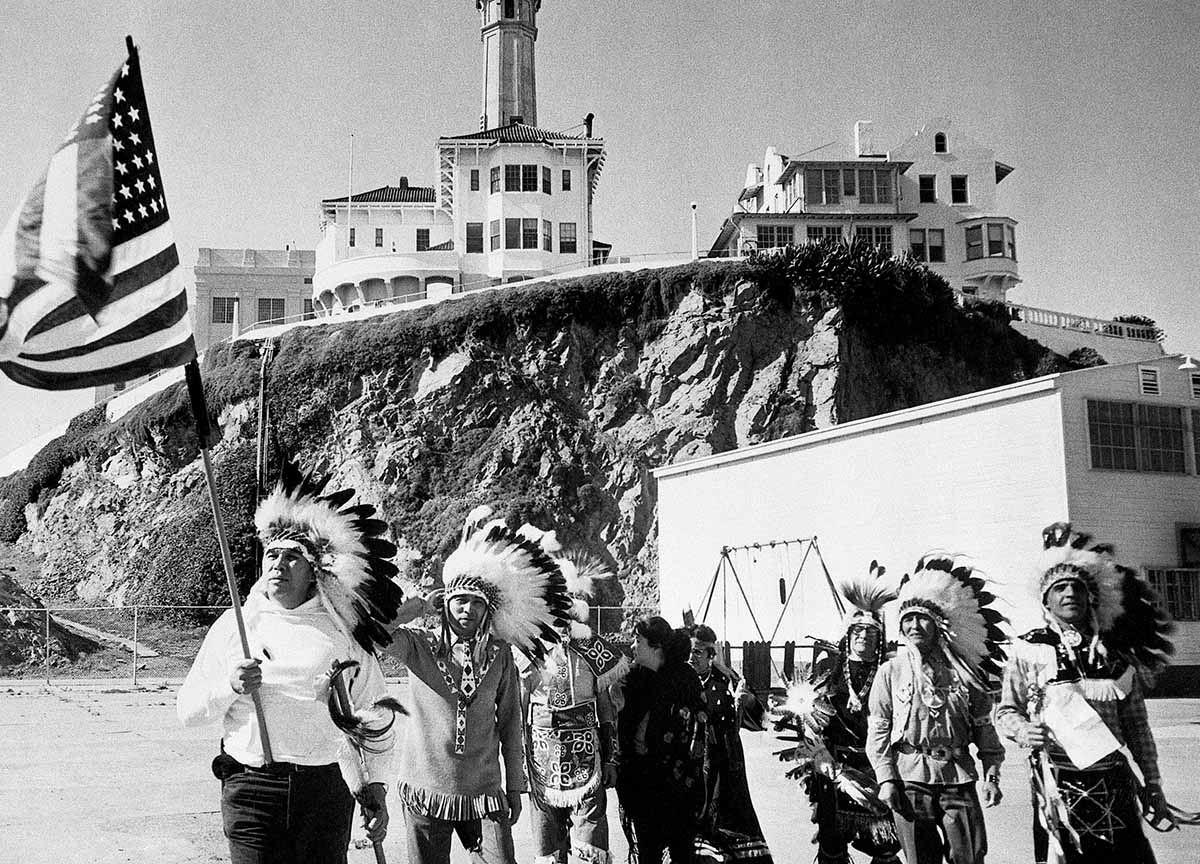

Treuer is especially strong on the rise, from 1969, of Native American Indian protest and of the American Indian Movement. This period saw the occupation of Alcatraz Island in protest against Indian unemployment rates at ten times the national average and endemic poverty. Rather than glorify the protest leaders, whom Treuer admits were ‘obsessed with image and given to grandstanding’, he contrasts the different ways resistance and tradition combine in a family member of the same generation, his uncle Bobby Matthews.

A dope-smoking wild rice picker who routinely works dawn to dusk to make a living, Bobby is a superb example of Indian entrepreneurship. Treuer presents him voicing the sort of avaricious thirst that would make characters such as Gordon Gekko or ‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ proud. After enjoying the familiar first release from a drag on his joint, Bobby remarks:

the Creator or God or whatever you call it made the universe and all the beings in it and put this tree here and that bush there and he made the beavers and the deer and the plants that are good to eat and the ones that are good for medicine. And I look out over that creation and sometimes I don’t see it like other people do. I look out at all of it and what I see is money. And by God I am going to find a way to liberate it out of there.

Such a message is funny, but also highly disruptive of the cherished narratives about American Indians routinely prioritised by the liberal left. Indian resilience, self-help, hard work, early adoption of technology, appetite to compete for public office and a desire to enshrine high levels of female leadership – these things are not actually new, but how Treuer highlights their impact since the late 1960s is.

The post-60s era is justifiably presented as a turning point, when top-down control exercised on Indian people began to loosen its hold: 1964 was the first time Indians were mentioned in a State of the Union Address by a president, not as belligerent enemies or a ‘problem’, but as American citizens deserving of government help to achieve their shot at the American Dream. The 1972 Indian Education Act and 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act were transformational and by the 1980s a recognisable Indian middle class had begun

to emerge. The 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act allowed some tribes to get seriously rich, but changed little for most. However, between 1990 and 1997 the number of Indian-owned businesses grew by 84 per cent. Between 1990 and 2000, the income of American Indians grew by 33 per cent and Indian poverty dropped by seven per cent. More than 80 Indians ran for public office across the US in 2018. Record numbers were women. The numbers of Native young people enrolling in college has doubled in the last 30 years.

Despite this, the usual emphasis in histories of America’s native population is upon pervasive American Indian structural disadvantage, high mortality rates, poor health provision, poor infrastructure on reservations, treatied rights being contravened, systemic lack of environmental justice and the grim history of colonialism. Of course, some of this is in Treuer’s book, too: but his main purpose is to displace the narrative of Indian defeat that has been central to the stories America has told for generations.

He sees that narrative, whether told about Indians or by Indians, as fundamentally disempowering. It has profound implications for Indian self-esteem and aspiration. What especially irks Treuer is the pervasive notion that Indians are dead and their cultures destroyed, an idea he blames on Dee Brown, the recently deceased, non-Indian author of Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. In that book, Treuer writes, ‘Our history (and our continued existence) came down to a list of the tragedies we had somehow outlived without really living: without civilization, without culture, without a set of selves.’

It may have happened because of marketing pressure, but I wish Treuer had contextualised his book in some other way than as an attack on Brown. Brown was the publishing sensation of the Vietnam-era and taught the reading public hard lessons about the brutality of their domestic history with obvious parallels to contemporary foreign policy. A University of Illinois librarian, his forensic attention to ethnographic records allowed him to highlight individual Indian voices of the past and upturn the dominant narrative of his day – that the West was ‘won’ by tough, white pioneers who settled ‘virgin’ lands devoid of indigenous communities. His book had such a tremendous impact and was so meticulously researched that the Dakota activist and scholar Vine Deloria Jr said he wished he had written it. But such a concern, perhaps, means I have too much respect for my elders. In this, I could be behind the times.

The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present

David Treuer

Corsair

512pp £25

Joy Porter is Professor of Indigenous History at the University of Hull.