In purgatory with Dante | History Today - 5 minutes read

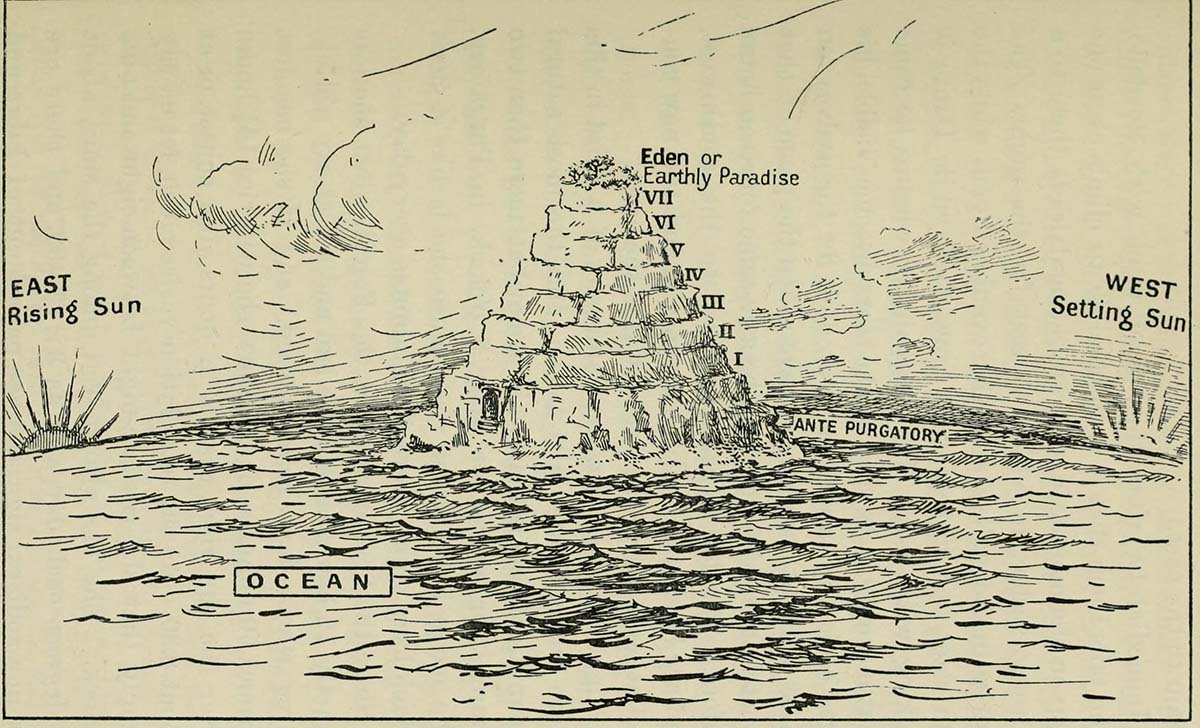

Those destined for an afterlife have been consigned to many different places. Christians often dispatched the damned to an eternity of suffering deep inside the earth. Jean-Paul Sartre pronounced that Hell was other people, while a recent illustrated version of The Divine Comedy features a perpetual nightmare of ATMs and fast food outlets. In two early lectures at the Florentine Academy, Galileo Galilei applied the latest mathematical techniques to the architecture of Dante Alighieri’s subterranean Hell, concluding that the poet’s imaginary structure was realistically self-supporting, just like Filippo Brunelleschi’s dome on top of the nearby cathedral. A less permanent fate awaited sinners judged capable of redemption, who toiled upwards for a prolonged process of purification in Purgatory which, according to Dante, lay on an island mountain located at the antipodes of Jerusalem, the only land in the southern hemisphere.

In an extraordinary new book about Dante (and much else) by Tracy Daugherty, an American professor of English and Creative Writing, the heroine is not Beatrice Portinari, but an Englishwoman from Plymouth named Mary Acworth Evershed, née Orr (1867-1949). Already infatuated with Dante after a visit to Italy, in 1890 Orr went to live for five years with her sister in New South Wales at a spot she identified as Dante’s Purgatory. Increasingly fascinated by astronomy, she used her own observations to compile the first published charts of southern stars, while also maintaining an obsession with Dante’s cosmological references. It was the Italian poet who later sustained her during a particularly miserable expedition with her husband. Trudging ankle-deep through a rice field and brushing wasp nests away from their instruments, she pondered existence beyond the grave.

Orr’s more scholarly analyses culminated in Dante and the Early Astronomers – the origin of Daugherty’s somewhat contrived title. Published on the eve of the First World War by an unknown woman isolated in an Indian hilltop observatory, for decades it received little attention. Daugherty’s book records his detective work along a tortuous trail of clues to uncover an elusive woman whose life stretched long beyond the Victorian era. Far from being a straightforward biography, this book interweaves its subject’s multiple journeys – geographical, intellectual, emotional – with snapshot summaries of topics rarely brought together, including Indian nationalism, solar science, Christian dialectics, relativity and Virginia Woolf. Daugherty’s style is lyrical verging on whimsical (‘At the heart of existence is the eroticism of the stars, the dynamics of desire’) and for support in unfamiliar territory, he leans heavily on quotations from other writers. In contrast, the sections sourced from original letters and diaries are vivid, revealing not only an exceptional woman, but also insider details of what actually happened on field trips – the disasters, quarrels and disappointments not recorded in official reports.

Orr embarked on her first major expedition in 1896, when the Royal Astronomer of Ireland, Robert Ball, led 60 self-funding astronomers to a remote Norwegian island for a solar eclipse predicted to last 106 seconds. Striding around the deck in his buffalo-skin coat (essential gear for star-gazing, he declared), Ball had little time for amateurs, especially female ones. Tempers frayed as local goats purloined the food, while Ball bored the party with his long monologues. At two in the morning, a bugle call alerted passengers that the big event would soon be upon them – but although the air darkened on cue and the birds fled, dense black clouds concealed the spectacle from view. Noting an atmosphere of collective shame at failure, Orr was reminded of Dante’s penitential shades.

Over the next ten years, Orr pursued an independent astronomical career, once lugging a large refracting telescope on an expedition with four other women to Algiers, where – unlike Ball – they successfully observed a total eclipse from the rooftop of the British consul’s villa. Back home in Surrey, she set up her own observatory, published a paper on variable stars and struck up friendships with other female astronomers. Her future husband, John Evershed, followed a similar trajectory, but although their training was comparable, she was obliged to remain an amateur while he was labelled a professional. When he was invited to become assistant director of a mountain-top station in the Palani Hills, she agreed to marry him and join the ranks of astronomical trailing spouses.

At the Indian observatory, the roof leaked, long skirts restricted Orr’s mobility and Evershed was frequently depressed, despite refusing to wear the thick flannel vests designed to protect delicate intestines against cholera. The well went dry, which made it difficult to process photographs, and the telescope mirrors warped in the hot sun. While jackals howled outside, she consoled herself with her piano and Dante’s reflections on feelings of exile. She took advantage of a temporary absence of sunspots to complete her study of Dante, crediting the Indian assistants who helped her to check his descriptions against actual observations.

The couple stayed almost 20 years in India, a period that included another disastrous eclipse expedition, when Evershed’s photographs all failed. This time the weather was perfect, but he angrily blamed the shoddy British equipment for being inferior to that of his Californian competitors. After the couple returned to England, he experienced what it felt like to be an exile, a second-class Anglo-Indian with no servants to admire him. Perhaps he learnt to empathise with his wife and her many talented friends. Far from mere number-crunching human computers, they made substantial contributions to science, but were forced to linger in the outer limbo of amateurship.

Dante and the Early Astronomer: Science, Adventure, and a Victorian Woman Who Opened the Heavens

Tracy Daugherty

Yale

214pp £18.99

Patricia Fara is Emeritus Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge.