Warsaw in Flames | History Today - 10 minutes read

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising is one of the events most readily associated with the history of the Holocaust, a focal point of Holocaust commemoration. Even as the war continued, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising allowed survivors to put resistance, rather than victimhood, at the centre of the Holocaust narrative. Their resistance symbolised strength, defiance and rebirth, a strong message that carried across borders. In the new state of Israel, among those Jews who remained in Poland, and in Jewish communities around the world, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was portrayed as part of a struggle for Jewish survival and, more broadly, for human freedom and dignity.

By the eve of the Uprising in April 1943 the Warsaw Ghetto had been reduced to a fraction of the space it had occupied when it was first established in November 1940. By 1943, it was divided into the ‘workshop area’, inhabited by those who lived there legally, employed in large workshops; the so-called ‘small ghetto’, inhabited by employees of the Werterfassung (a formation responsible for the requisition of goods left behind by those deported to Treblinka); and those who lived in the ghetto illegally, the so-called ‘wild’ inhabitants. It is estimated that around 50,000 Jews were in the Warsaw Ghetto during the Uprising, after more than 300,000 were murdered during the deportation action beginning in the summer of 1942 and another 100,000 had died in the ghetto of starvation and illnesses.

Yet commemoration of the Uprising centred around only the few hundred of those who were active in guerilla fighting: members of the Jewish Fighting Organisation (ŻOB) and the Jewish Fighting Union (ŻZW). Understandably, the bravery of typically very young fighters was more acceptable for commemoration than civilian deaths in bunkers, burning alive in apartment buildings, suicides, hideouts and Nazi attacks. However, the tens of thousands of civilians trapped in the burning ghetto are also part of the story of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising; their defiance and unwillingness to submit to German demands was the key reason why the Uprising lasted as long as it did.

Hideouts

On 19 April 1943, the eve of Passover, German units of the Waffen SS and the police, led by the commander of the SS and police in the Warsaw District, Ferdinand von Sammern-Frankenegg, entered the Warsaw Ghetto with the aim of carrying out the final deportation action. Workshop employees were to be transported to work camps in the Lublin area; those remaining in the ghetto illegally were to be sent to Treblinka extermination camp. However, once they crossed into the ghetto, the German units were confronted by between 300 and 500 fighters from the ŻOB, and around 250 fighters from the ŻZW. This was unexpected and, at least initially, slowed the Germans down. The task of the final liquidation of the ghetto was then taken over by Jürgen Stroop, who would later receive an Iron Cross (1st Class) for his brutal actions.

Somehow the insurgents – with no arms or outside support – managed to keep fighting for days. After that, a few dozen of them left the ghetto through the sewers, while others joined civilians in bunkers. Small-scale attacks on German patrols were still undertaken, mainly at night. For the remaining month of the Uprising, German units systematically destroyed the ghetto and with it the hidden city of civilian bunkers and hideouts.

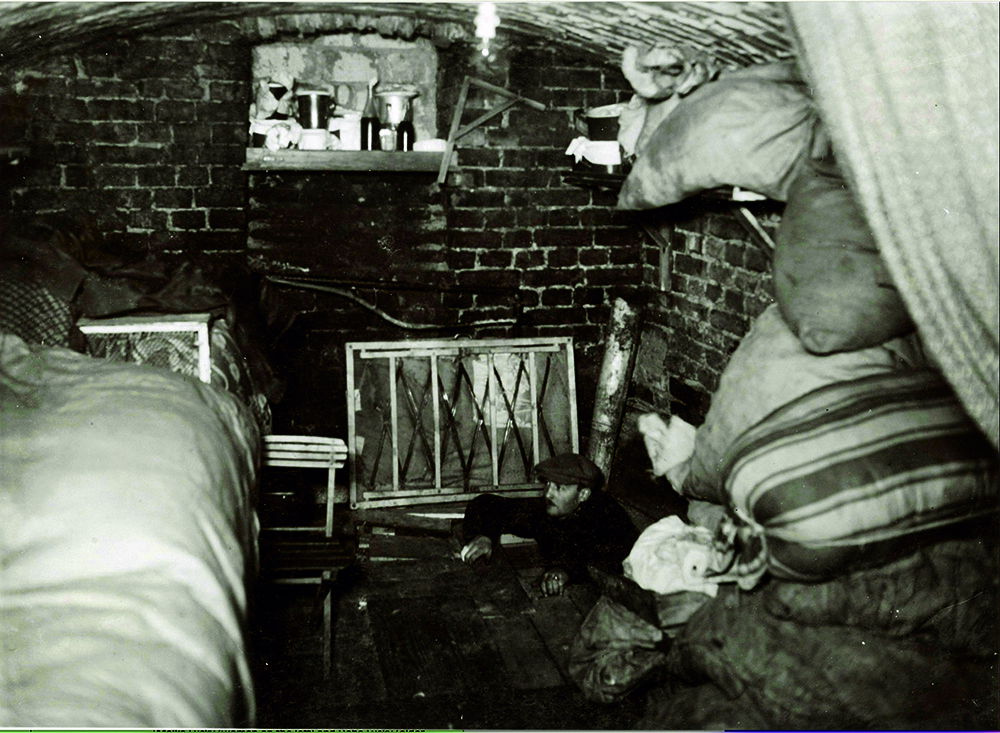

The construction of hideouts had begun in January in anticipation of mass deportations, prepared in attics and underground. Subterranean hideouts were usually much more elaborate and better equipped. Bunkers were constructed in or under basements, often by connecting the basements of adjoining buildings to create a larger space. Some were built under courtyards. The equipment and quality of bunkers depended on the financial means and skills of those preparing them.

A member of a youth organisation recalled:

The work went on day and night with great fervour. Bunks, floors, and stairs were built. A well was dug. The wood needed for construction was taken from apartments (that is, apartments that had been abandoned). The construction took six weeks. While the building went on, food supplies were prepared, a stockpile for the future.

The hideouts were designed and equipped to house those who built them. Despite this, a young woman who entered an empty bunker under construction described in her diary the feeling of dread she felt when she imagined being confined underground: ‘Being buried alive I imagined only as our last resort.’

The bunkers could not house everyone when the German units entered the ghetto, and the majority of its inhabitants hid wherever they could or wandered through the burning ghetto suffering from hunger and thirst. The bunkers quickly became horrendously overcrowded. One inhabitant wrote about his experience in the bunker he had constructed:

Instead of 25 people, there were 60: children and elderly whom we could not refuse to let in and leave to their fate. The stench was horrendous, it was very hot, the air was heavy, filled with moisture and sweat.

Another said that the lack of air became so severe that she could not light a match in the bunker. A young ŻOB fighter noted in a diary on the eighth day of the Uprising:

Our building is also burning. The building on the Zamenhof Street side, where people were hiding, is also going up in flames. People escape from there and come to us. It looks like disaster is drawing near. The shelter is very crowded because of the large number of people, and many more want to get in. They bang on the opening; they ask us to let them in. The people shout and argue. Everyone wants to get into the hideout. It’s hard to give permission to enter … Because of the smoke and the stench, staying in the basement became almost impossible. We seal up the cracks in the door with strips of paper … The air in the basement is terrible. People are nearly suffocating. Many of them faint, lose consciousness. The situation is dire. Sleep is not feasible because of the danger of asphyxiation.

Silent suffering

Due to the constant risk of discovery, daily life in the bunker had to be carried out in silence. As one of those in hiding wrote: ‘Our main defence – deepest silence.’ Inhabitants of his bunker had to remain silent every day from about 7am until 8pm. As a consequence, people lived in a constant state of anxiety, listening for approaching steps, explosions and, increasingly, the sounds of executions as neighbouring bunkers were uncovered:

In those days nobody was reading anymore, we spent days listening out for danger and short nights trying to catch some sleep. During the day we had to ensure silence and limit all our physiological needs.

Many bunkers quickly became infested with lice and other insects. The air inside them was stifling, both from the number of people gathered in a small space and from the fires ravaging the ghetto. They were also running out of food and water. As electricity in bunkers was quickly cut off, there was no way of cooking. The constant anxiety inevitably heightened tensions between those in hiding; children, including babies, were drugged to remain silent. An anonymous young woman hiding in a bunker recalled:

Suddenly the silence is broken by the cry of the child. I sweat all over, curse words fell from all sides on the poor, unaware being. Someone says we must suffocate it, or it will betray all of us.

People spent days lying on their bunks in complete silence, leaving at night, if at all.

Fire

Despite this, bunkers remained the only means of ensuring at least temporary survival; those who could find shelter in them were in a better position than those in hideouts built into apartment buildings and attics. Trapped in burning buildings, these people were among the first victims of the Uprising. Testimonies include frequent descriptions of people jumping from windows to escape fire. One ŻOB fighter recalled:

I go out onto the street. It’s burning. Everything all around is going up in flames. The streets: Miła, Zamenhof, Kurza, Nalewki, Lubecki. All these streets are in flames. Workshops, apartments, shops, and entire buildings are on fire. The ghetto is nothing but a sea of flames. A very strong wind is blowing, that makes the fire burn harder and carries sparks from the burning buildings to those that have not yet been ignited. The fire consumes everything. The view is horrifying, shocking. The fire spreads so rapidly that people don’t have time to flee their homes and perish in a tragic way … Because of the fire there’s much traffic in the street. People with bundles of belongings run from building to building, from street to street. There is no salvation, no one knows where to hide. In desperation they search but there’s nothing – no rescue, no refuge. Death reigns over all. The ghetto’s walls are surrounded. There’s no entering or exiting. People’s clothing burns on their bodies. Cries of pain, weeping. The buildings and the bunkers are burning. Absolutely everything is engulfed in flames. Everyone wants to be saved, everyone wants to save his own life.

The bunkers were flushed out by the Nazis using gas, which was also used to cut off escape routes through the sewers. Some of the captured were forced to reveal hideouts. After bunkers were uncovered, their inhabitants were taken outside, where they were often stripped naked and searched for valuables. They were usually murdered on the spot. Thousands more died from being gassed or buried alive under the rubble of burning apartment blocks. Others were taken to the camps in Majdanek, Trawniki and Treblinka. Those who survived described the horror of being led through the streets of the burning ghetto, strewn with bodies of those murdered. One boy, aged 13, recalled:

On the eighth day of the uprising they burned the house where we were hiding. My father was killed by the German beasts, me, my mother and two younger brothers were taken to the Umschlagplatz, where we stayed for one day. We were then loaded onto carriages, 120 people per carriage. We travelled for two days without food or any water. On the third day we got to Majdanek, where I was disconnected from my mother.

Extinguished

On 8 May Germans discovered the bunker hiding the leadership of the ŻOB at 18 Miła Street. Approximately 100 fighters, including the leader of the Uprising, Mordechai Anielewicz, died of asphyxiation or killed themselves to avoid capture. According to Jürgen Stroop, 56,000 Jews were murdered in the ghetto or deported during the Uprising, and 631 bunkers uncovered. While these numbers are exaggerated, they give us a sense of the numbers of people who were murdered over the month of the Uprising, whether with weapons in their hands, or without, in the bunkers and attics of the burning ghetto. On 16 May Jürgen Stroop ordered the Great Synagogue at Tłomackie to be blown up. He finished his daily report with the words: ‘Es gibt keinen jüdischen Wohnbezirk in Warschau mehr!’ ‘The Jewish quarter in Warsaw does not exist anymore!’

Katarzyna Person is Head of the Research Department at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

Source: History Today Feed