Bulgaria’s Traumatic Revival | History Today - 9 minutes read

Bulgaria has the single largest Muslim minority population of any country in the European Union. Around 15 per cent of its roughly seven million citizens identify as Muslim (compared with less than five per cent in the UK). The group is ethnically diverse – Bulgarians, Roma, even a small Gagauz community – but it is largely dominated by so-called ‘Turkish Bulgarians’. Their presence in the country today evokes the long and uncomfortable history of Ottoman rule in the Balkans and poses questions about how that period is remembered.

The Ottomans arrived in the Balkans in 1354. By the 15th century they dominated much of the region, from the Peloponnese to the Danube. In the 19th century, after nearly 500 years of Ottoman rule, nationalist fever spread across the Balkans. A number of ‘national revival’ movements in the region sought to mobilise ethnic, religious and linguistic identities into political movements in opposition to Ottoman power. Although none was successful in bringing it to an end, the involvement of Russia and internal instability within the empire eventually led to the collapse of Ottoman rule. Most Balkan states gained independence by the turn of the 20th century – Bulgaria in 1878 – and the Ottoman Empire was replaced by a new Turkish state in 1923.

Literary heroes

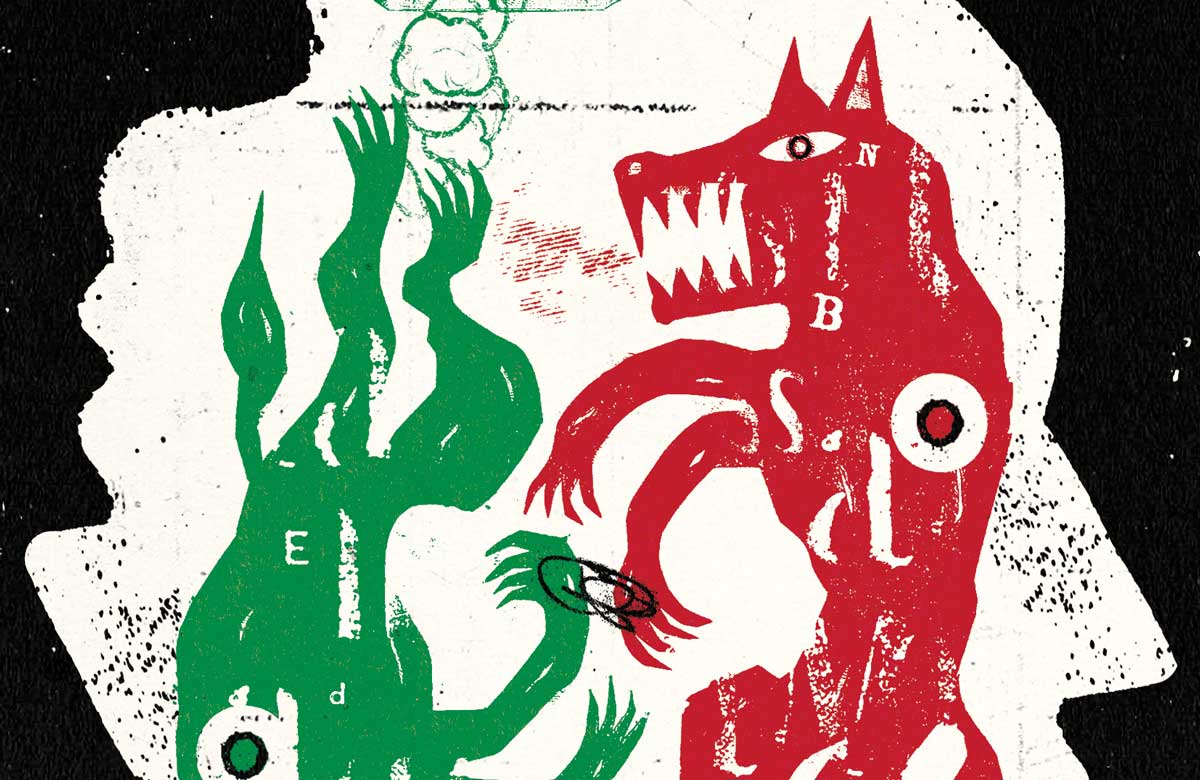

Literature played a large role in Bulgaria’s ‘National Awakening’, the first phase of the National Revival. In the works produced during this era, identities of ‘Ottoman’, ‘Turk’ and ‘Muslim’ were grouped together as one. This has proved to be one of the movement’s lasting legacies, as Bulgaria’s far-right parties continue to use the country’s Muslim population of Turkish speakers as a stand-in for, and ongoing reminder of, the old Ottoman enemy. At the heart of this generic identification is a deeply ingrained feeling of trauma.

Expressions of this trauma are evident in the nationalist revival poetry of the 19th century, which deems the period of Ottoman rule as robstvo, literally ‘slavery’. Modern Bulgarian education includes stories of the country’s nationalist organisers being captured and killed by the Ottoman authorities, regardless of whether they were orators or mountain bandits. The quintessential novel of the period, Ivan Vazov’s Under the Yoke (1894), tells the story of the return of an exiled rebel to his home village in the days leading up to the failed April Uprising of 1876. Inspired by a similar Serbian uprising in Herzegovina in 1875, the April uprising was swiftly and brutally put down by the Ottomans. Despite being a difficult read in places, Vazov’s novel is a set text for Bulgarian school pupils as young as 13. One of the most famous poems from the period, Hristo Botev’s 1873 ‘Hadzhi Dimitar’, tells the story of the famous voyvoda (rebel leader) bleeding to death after an encounter with an Ottoman garrison. ‘Sing these mournful songs, slave women! / Shine, sunshine, in this enslaved land!’, Botev writes. ‘He who falls in a fight for freedom, does not die.’ These final lines can be found across Bulgaria, including on the side of the Municipal Electricity Building in Sliven, Hadzhi Dimitar’s hometown. Bulgarians are reminded of sacrifice while paying their electricity bills.

The stories we tell

The 19th-century romanticisation of the national liberation fight made sense in its immediate aftermath; authors like Hristo Botev knew many of the men who had died organising it. Over the course of the 20th and 21st centuries, however, this memory of trauma has spread and solidified, now occupying a central place in Bulgaria’s national identity.

In 1964 Anton Donchev wrote Time of Parting, a self-proclaimed historical novel set in 1668, well before the national awakening. The book narrates the arrival of a enichar, a high-ranking Ottoman official, in a small village in south-west Bulgaria. The enichar, Karaibrahim, is eager to enforce conversion to Islam and burns much of the village in the process. A war rages, with villagers hiding in the mountains. Many are killed publicly, after refusing to convert. In 2009 Bulgarian National Television began a campaign to identify Bulgaria’s favourite book. Time of Parting, a mid-20th century reimagining of the 17th century, came second. Under the Yoke, Vazov’s 1890s account of the 1870s came first. Nationalist rhetoric based around the trauma of the Ottoman era has shown its enduring popularity.

In 1988 Time of Parting was adapted for the screen. Funded by the socialist government of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria in its dying days (the first free elections in Bulgaria since 1931 were held in 1990), the film was, at the time, the biggest production in Bulgarian cinematic history. I once met a bus driver in south-western Bulgaria who proudly told me he was an extra in the film. It did not bother him that he had been cast as an Ottoman soldier.

The film dramatises some of the novel’s most disturbing scenes, which are well known to anyone who grew up in the country. Perhaps the most memorable is the public execution of the men who refuse to convert to Islam. They are brought forward into the village square and asked whether they renounce Christ. Upon their refusal, one man is beheaded, another torn to pieces after being tied to two horses made to run in opposite directions. In 2015, to celebrate 100 years of Bulgarian cinema, Bulgarian National Television ran another survey to find the public’s 100 favourite Bulgarian films. Time of Parting won: it is the Bulgarian film of the century.

After the fact, fiction

There is a problem with the book and the film, however. It is this: the 1668 pogrom against Christians in the mountain region of the Rhodope probably never happened. Anton Donchev claimed that his book was based on authentic historical documents. Recent work by Bulgarian academics has shown this to be untrue. Among the sources used by Donchev is the chronicle of a priest, published in Vienna by the Bulgarian nationalist Stefan Zahariev in 1870. Maria Todorva, author of Imagining the Balkans (1997), is correct when she writes that such a source ‘cannot be used as an example of a document from the seventeenth century, nor as an authentic eyewitness account of mass forced conversion’.

Rather, as the historian Stefan Dechev has persuasively argued, this document and another three texts which form the small corpus of questionable accounts of violent forced conversion in the early modern period, need to be situated firmly in the 19th century in which they were written. As Dechev writes, each source has a pressing contemporary concern – namely, to explain why many Slavonic-speakers in the Balkans were practising Islam.

The nationalist literature of the 19th century was born out of a political struggle with the Ottoman imperial regime, one defined by a sense of repression and hardship. The trauma it produced was inherited by 20th-century literature and film, works that are today revered as the epitome of Bulgarian culture.

Life under an exploitative imperial regime was without doubt difficult for the population of the Balkans, especially for non-Muslims, who had additional taxes imposed upon them. But the 20th-century Bulgarians who chose these books and films as their favourites never experienced that particular trauma. In reality, the 20th century proved much more traumatic for Bulgaria’s Turkish and Muslim minority. In addition to the violent population exchanges seen in the Balkans in the early 20th century, the 1980s – the decade in which Time of Parting was released – saw some of the most aggressive anti-Turkish legislation in Bulgarian history. In 1984-85, the People’s Republic of Bulgaria enforced name-changes upon Turkish-speaking Muslims throughout the country. Over 800,000 people had to shed their Muslim names for ‘traditional’ Slavonic ones. By the summer of 1989, a year after Time of Parting was released, over 350,000 citizens were forced to leave for Turkey, a country in which they had never lived.

Shared enemies

A sense of national trauma can be a powerful political weapon. In this, Bulgaria is not an exception. In 2019, Christian Davis wrote in the London Review of Books about the development of a conspiracy theory in Poland, which held that 200,000 Poles were murdered in a German death camp in Warsaw. While the camp did exist, and approximately 20,000 Polish Jews, non-Jewish Poles and non-Polish Jews are estimated to have died there, this newly mythologised mass murder permitted talk of a ‘Polocaust’. This permitted conspiracists to undermine Jewish claims of victimhood, but also to blame Germany for covering up the atrocity.

Of course, populist trauma builds community on shared enemies, not shared values. Given how swiftly identifying those responsible for perceived past crimes can lead to inflicting violence against them, the populist mobilisation of trauma politics must be constantly interrogated. But in Bulgaria there is another unique historical hurdle to this interrogation: namely the memory of the period of Soviet-aligned but independent socialist rule between 1946 and 1990.

Modern Bulgarian perceptions of this period vary between fond nostalgia and deep suspicion. As inequality widens in Bulgarian society this nostalgia is no longer distributed strictly across generational divides. Yet, as the old Bulgarian saying goes, the worst thing you can call a man is a liar or a communist.

Ambiguity towards the socialist past stands in stark contrast to the prevailing narratives about the Ottoman era. With its historical remoteness and its clear heroes and villains, the story of Ottoman rule offers unity to an otherwise divided people. This simplicity is attractive, but its healing potential is significantly curtailed by the threat it poses to minorities in the country today.

It’s complicated

Recently, Bulgarian academics have called for new ways of thinking about history, both Ottoman and communist. They have demanded that we complicate, rather than simplify, our understanding of the past. The starting point is to move away from essentialist ideas about nationalism and the continuity of Bulgarian identity from the Middle Ages to the present day. From this foundation we might establish a space to reconsider the perception of Ottoman rule and to think constructively about the more recent socialist past. But, if the reading and viewing habits of the Bulgarian population are anything to go by, the country has a long way to travel before overcoming the trauma of bygone times, let alone facing the trauma of yesterday.

Mirela Ivanova is Lecturer in Medieval History at the University of Sheffield.

Source: History Today Feed