Belarus Remembers | History Today - 9 minutes read

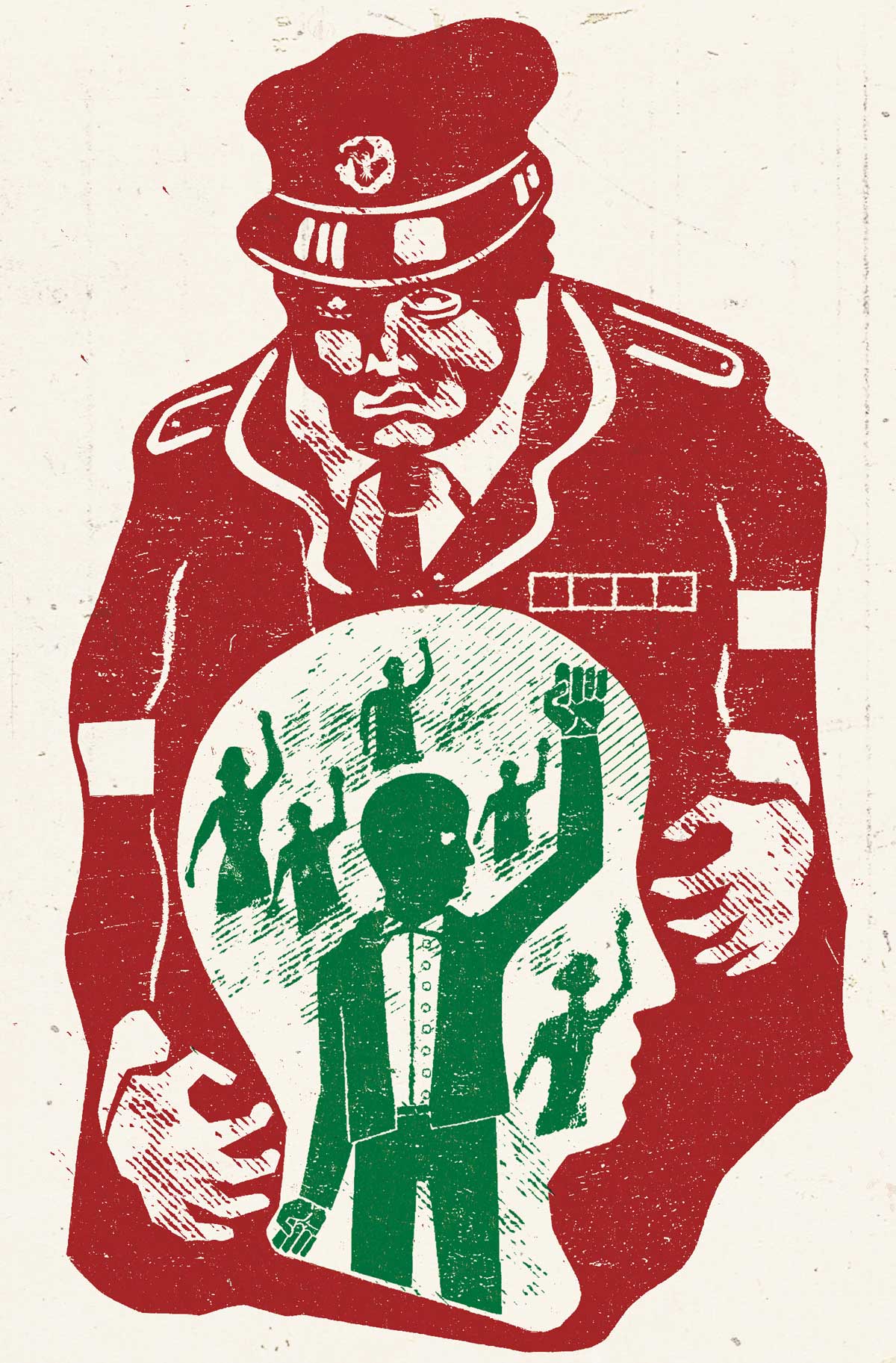

The Belarusian authorities described as ‘war’ the protests that have gripped the country since the fraudulent presidential elections of August 2020. This was more than a crude attempt to misrepresent the reality of the police and the army attacking peaceful protesters with brutal force. It was an effort by the embattled regime to use one of the country’s most significant historical memories – that of the Second World War – in its fight against the greatest challenge it has faced in its quarter century of existence.

References to the Second World War are ubiquitous in the current protests. This might seem surprising; for nearly 26 years it was president Alyaksandr Lukashenka who led state efforts to cultivate public memory of the war to secure popular support for his regime. Lukashenka once claimed that his father died fighting in the war, a story contradicted by the fact that he himself was born nine years after its end.

But for those who endured the police beatings and state-sanctioned torture in 2020, the most obvious comparison of their ordeal was the brutality of the Gestapo and the Nazi camps. In August, potash miners in Soligorsk threatened a strike because, they said, the country was being turned into a concentration camp. When the police locked a group of demonstrators in a Catholic church near the parliament building, it reminded the nation of how, during the war, the Nazis had herded their compatriots into churches before setting them on fire. An opposition news website ran a story with the title ‘It felt like Khatyn’, a reference to a Belarusian village that was burnt along with its inhabitants (and now the site of a famous war memorial).

War talk

Describing the regime as ‘fascist’, the authorities as ‘occupiers’ and the police as ‘punitive detachments’ is a key part of the protesters’ rhetoric. A group of computer hackers, who have taken to crashing government websites, are calling themselves ‘cyber partisans’, hinting at Belarus’ Soviet-era reputation as a ‘partisan republic’. A strategy of causing trains to drop speed has been dubbed ‘the railway war’, a term the wartime Belarusian partisans used for their deadly attacks on German trains. In a nod to a well-known Soviet mobilisation poster, an enormous drawing of the opposition leader Maryia Kalesnikava was projected onto the side of an apartment block in Minsk shortly after her failed deportation, depicting her as a symbol of the motherland, a red-clad figure holding her torn up passport. In November, when the country mourned 31-year-old Raman Bandarenka, beaten to death by regime-sponsored thugs after he asked them to stop removing white-red-white ribbons from his apartment block’s courtyard, candles were lit in his honour at several war memorials. A national mass rally later that month was named ‘March against Fascism’.

The war for the war

The authorities have tried to outflank the protesters by claiming the memory of the war as theirs. They have repeated well-worn accusations that demonstrators carry collaborationists’ flags. During the second mass rally in Minsk, the army surrounded the site of the original protests on the pretext of protecting the war monument located there. Lukashenka has regularly hinted that the unrest was provoked by the West, which plans to attack Belarus in a repeat of the invasion of 1941. The early demonstrations were drowned out by loudspeakers blasting Soviet-era songs, although the authorities sensibly stopped the broadcast of the wartime mobilisation anthem ‘Holy War’, which begins with the words ‘Rise, great country, rise to the battle!’ Ultimately, however, the Lukashenka regime’s efforts in this memory battle were undermined by its use of violence, which could not help but conjure associations with Nazi brutality. His recent instruction to the police to ‘take no prisoners’ has not gone unnoticed.

Certainly, these are not the only historical memories that inform the protests. Its main visual symbols, such as the white-red-white banner – first used by the failed Belarusian People’s Republic in 1918 – are not Soviet. Comparisons with the Stalinist NKVD and terror have also been made. One rally in October centred on Kurapaty, near Minsk, the site of the mass burial of victims of Stalin’s ‘Great Purge’. But evoking memories of Stalinism does not exclude references to the war. The Kurapaty march saw some protesters shout ‘fascists’ at the attacking police, and one Telegram channel compared the police response to Hitler’s desperate efforts to save his regime in 1945.

The problem for Lukashenka is that public memory of the war has a far older pedigree than his regime. The entire identity of postwar Soviet Belarus was built on its war experience and, unusually for Soviet war memory, partly on its trauma.

Initially discouraged under Stalin, the state-sponsored memory of the ‘Great Patriotic War’ blossomed into a veritable cult under Leonid Brezhnev. By then, former partisan leaders already dominated the local politics of Soviet Belarus. Between 1956 and 1980 the republic’s Communist Party was headed by former partisans: Kiryla Mazurau (1956-65) and Petr Masherau (1965-80). They led efforts in shaping and consecrating the official history of the Belarusian wartime partisan movement, persuading Moscow to recognise the importance of the previously neglected Minsk underground resistance and successfully lobbying for Belarusian cities and regions to receive national war hero status. Their efforts helped consolidate the Union-wide image of Belarus as a ‘partisan republic’ and a heroic contributor to the Soviet victory, while leaving out unpalatable stories of confusion, collaborationism or partisan violence.

Painful memories

However skewed, this postwar identity was not without just foundations: Belarus saw the largest partisan movement in the history of the war, which played a meaningful part in the Soviet military effort. But in the context of the ruthless German occupation (1941-44), it also exacerbated the horrendous plight of its civilians. The population of what is today Belarus endured awful suffering. Hundreds of villages were burnt, often together with their residents.

A significant majority of towns were destroyed. The occupying troops and SS death squads killed hundreds of thousands of civilians in retribution for partisan activity, while tens of thousands were killed, in turn, by the partisans. Belarus lost between half and two thirds of its Jewish population. Scores of survivors were deported or fled. Timothy Snyder has written that the war hit Belarus harder than any other European country: by its end, ‘half the population of Belarus had either been killed or moved’.

Such was the enormity of the trauma that it seeped through the usual barriers of Soviet censorship. The Khatyn memorial near Minsk, unveiled in 1969 as a monument to the burnt villages of Belarus, was strikingly out of keeping with Brezhnev-era monumentalism. Its focus on loss and trauma instead of heroism angered the Soviet Minister for Culture, Ekaterina Furtseva. She demanded, unsuccessfully, that it be torn down.

Soviet Belarus also broke the taboo on Holocaust remembrance by having the first monument in the Soviet Union dedicated specifically to Jewish victims. A modest obelisk with an inscription in Yiddish and Russian was erected in 1946 to mark the pit where 5,000 Jewish residents of the Minsk Ghetto were massacred on a single day in 1942. Built without the authorities’ permission, it outlived the Soviet Union. The memorial, known as Yama (‘The Pit’), was expanded in 2000 and now includes a sculpture of a line of people descending into the hollow.

Belarusian war literature, too, withstood Soviet attempts to purge the war’s memory of pain. One of the most important Soviet Belarusian writers, Vasil Bykau, did more than anyone to keep alive, but also complicate, the memory of the war in Belarus. His stories explored betrayal, fear and loss, aspects of the war that the authorities wished to gloss over. Bykau was harassed by the Belarusian KGB and heavily criticised in the Soviet press, but he also received the Belarusian Republic’s highest literary prize (twice). His works were adapted into films in the 1960s and 1970s.

Learning from the past

Dominated by heroism, yet able to recognise suffering and trauma, Belarus’ collective war memory survived the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991. Lukashenka’s regime capitalised on its patriotic myths. War memory has remained a consensus builder. A 2013 national poll by the Independent Institute of Socio-Economic and Political Studies showed the overwhelming majority of the respondents – over 78 per cent – agree that victory in the Second World War was one of the 20th-century events that Belarusians could be most proud of. Notably fewer (39 per cent) considered independence in 1991 to be an equal source of pride. The first ever declaration of Belarusian statehood in 1918 was backed by a meagre ten per cent of respondents.

This resilience of the Soviet-era collective war memory is not down to Lukashenka’s propaganda alone. In the late Soviet period, Belarus’ image as a heroic and loyal republic was closely bound with its postwar economic achievements. Belarus was transformed from a peasant backwater into an industrial centre and a scientific hub with its own nuclear research facilities. It became a success story of Soviet modernisation: living standards were high and the economy seemed to thrive even as the picture grew increasingly bleak elsewhere in the Soviet Union. A third of the respondents in the 2013 national survey named the postwar reconstruction and subsequent industrialisation as the events Belarusians should be most proud of.

Such attitudes have often prompted accusations that the country is stuck in the Soviet past. But it is this past that might now serve Belarusians well. Their profound aversion to violence, conditioned by tangible memory of a horrific war, helps explain why the police brutality has caused such widespread outcry, why it continues to galvanise formerly apolitical Belarusians and why the protests have remained stoically peaceful, bringing Belarus together as a nation.

Having wrested Lukashenka’s monopoly on the nation’s war memory from him, the protesters have shown that history – and the future – is on their side.

Natalya Chernyshova is Senior Lecturer in Modern History at the University of Winchester and is writing a biography of Petr Masherau.

Source: History Today Feed