The True Knights Templar | History Today - 5 minutes read

The way in which the Templars have been judged – and how they are currently portrayed – has been indelibly coloured by the way in which the order came to its end.

That end came in October 1307. Appropriately enough, it was Friday the 13th. As Philip IV’s fears over the Templars’ power reached their peak, raids took place in Paris and across the rest of France. The French Templars were arrested en masse and subjected to the most fearsome interrogations.

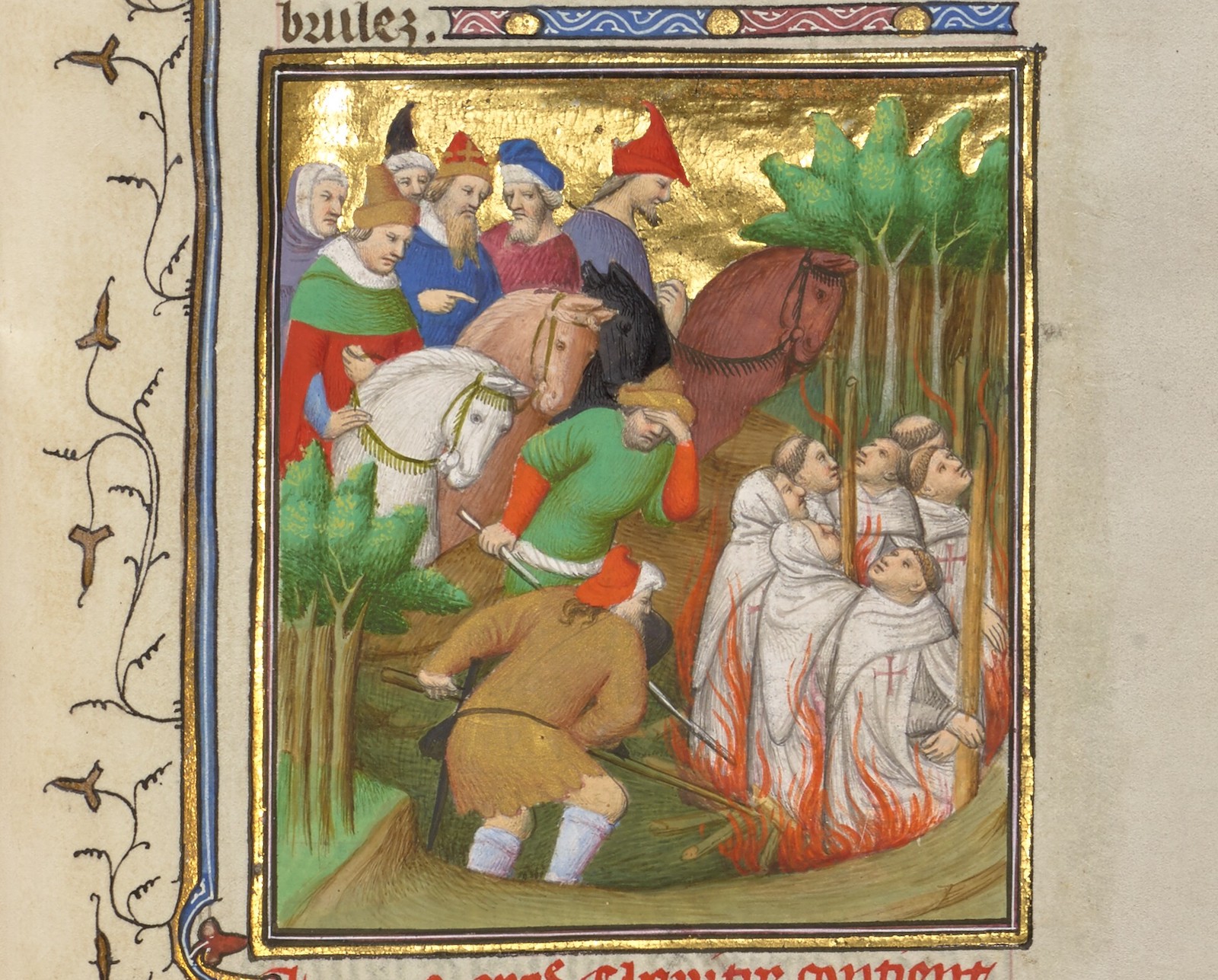

The brothers were accused of crimes that were said to have long taken hold and corrupted the order. In Paris, torture was used from the very beginning. Many Templar brothers died rather than make false confessions. But they were not super-human. Torture of this ferocity was effective – men eventually said whatever they thought the inquisitors wanted to hear.

It was revealed that the Templars had denounced Christ and regularly spat and trampled upon the cross. They had worshipped devils and idols, and created their own ‘anti-Christs’ for a new ‘anti-Christian’ religion. The Templars were shown to be a secret sect at war with the very heart of Christendom.

The charges were entirely spurious but, largely as a result of the extraordinary manner in which they were closed down, the Templars now have an enduring reputation for Satanism, bestiality and heresy.

The Templars’ reputation as warriors has partially survived, albeit in a twisted way. Their traditions of bravery and commitment in the field have been taken up by right-wing groups whose ideologies were alien to almost everything they stood for.

What is almost entirely forgotten, however, is that much of their real role lay in ‘state-building’ – as modernisers and as professionals. They brought military innovation and the benefits of a standing army to the Latin East; but, just as importantly, they made qualitative improvements to governments and societies across Europe.

The Templars helped professionalise the medieval states of Europe. They influenced royal strategy and policy making; created new local and international financial structures; developed innovative legal practices; acted as high level diplomats, brokering international peace treaties; tried to heal internal divisions and stop rebellions; introduced new, state-of-the-art economic and logistics practices on their own estates; and shared best practice in military affairs, training commanders before they encountered the uniquely dangerous nomadic enemies of Christendom in the Holy Land.

This was not altruism. The order needed peaceful, stable states so that kings could take their armies on crusade. But, altruistic or not, the end result was the same. Although the Templars could ultimately not save the Latin East, or themselves, the ironic by-product of their modernising endeavours was to help create the states we still see around us in Europe today.

Taking King John of England as an example, it is clear just what an important role the order had in moulding the states within which they operated. A popular ruler with charm and charisma can be forgiven a great deal. He is given the benefit of the doubt. He has reserves of loyalty. A ruler like John, however, was neither trusted nor trusting. Instead, he needed talented partners who would be able to help him by taking a longer-term and more unemotional view of the world – men such as the British Templars.

When John was in the disastrous process of losing Normandy, for instance, the brothers stepped in to limit the damage. They struggled to put a diplomatic settlement in place. The master of the British Templars, Aimery of Saint-Maur, was employed by the king from February 1204 in negotiations with the French. His objective was to try to broker a truce, no matter how humiliating, before Normandy collapsed altogether.

John continued to use the Templars in his attempts to recover his lost empire in France. In 1211-12, the order’s financiers and diplomats at the New Temple in London (the Templars’ headquarters in Britain) were engaged to provide money subsidies for the forces of the German emperor, Otto IV, in order to buy his support against the French. At least one British Templar emissary accompanied the emperor’s envoys back to Germany to help organise the transactions.

And, in the debilitating civil war that followed, the order continued to play their role as diplomats and military advisers, even at the short-lived peace agreement that was thrashed out at Runnymede on 15 June 1215 – ‘Almeric the master of the knights-Templar’ was one of the nobles present when Magna Carta was signed.

The Templars’ financial skills were also important. The New Temple became a major financial centre and the order was, on occasion, given responsibility for John’s war chest. When cash flow failed, credit was required too – the Templars provided loans, were instrumental in rebuilding the English navy and were even trusted enough to be put in charge of the royal jewels and regalia. The Templars helped keep the king’s administration afloat after his continental military adventures had failed. Regardless of what they thought of John, the Templars provided him with wise counsel and expert professional services, just as they did for most of the kings of this period.

The manner of the Templars’ suppression created the perfect breeding ground in which conspiracy theories could flourish. These are a bizarre parody of the truth. The enduring Templar legacy lies not in mad stories of secret grails and satanism, but in the way this small group of highly focused individuals helped to shape the states in which they lived.

Steve Tibble is an associate at Royal Holloway College. His latest book is Templars: The Knights Who Made Britain (Yale University Press, 2023).

Source: History Today Feed