Judges question search warrants in Kraft case - 6 minutes read

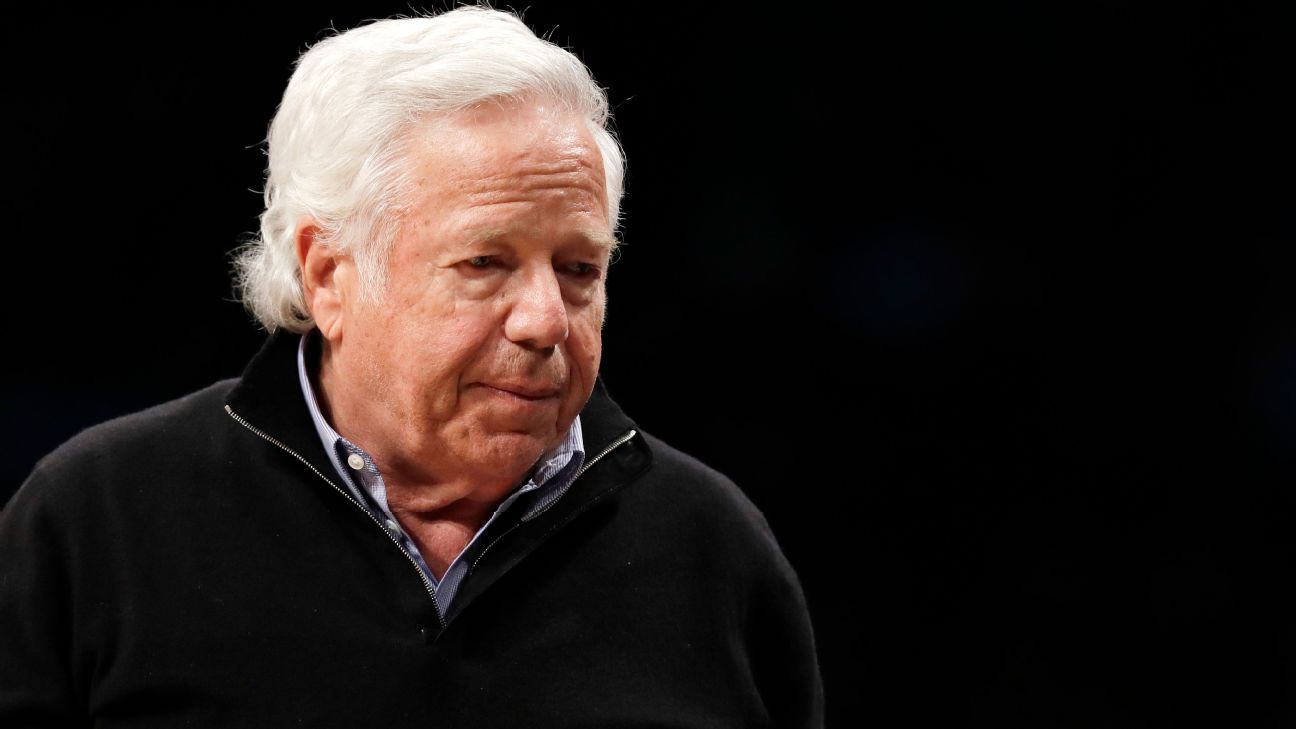

Robert Kraft's solicitation of prostitution case was back in court Tuesday, with the primary piece of evidence against the New England Patriots' owner, police video surveillance, at stake.

Florida prosecutors are trying to salvage the evidence after a state circuit court judge ruled last year that Jupiter, Florida, police improperly received and executed search warrants. Without that video evidence, legal experts have said the misdemeanor case against Kraft and 24 other defendants could fall apart.

A three-judge panel of the Florida State Fourth District Court of Appeal heard arguments via a Zoom conference call and may render a verdict as early as next week. Kraft did not appear in the virtual hearing, but could have watched via livestream along with the rest of the public.

The key question in the case is whether police "minimized" surveillance as required under the law. Kraft's attorneys convinced Judge Leonard Hanser last year that police violated the defendants' rights by running video indiscriminately for the entire three days of their investigation, failing to stop recording when it was clear that some parties were not receiving illegal services.

Florida deputy solicitor general Jeffrey DeSousa argued Tuesday that police were not required to specify how they would minimize surveillance in the search warrant request, and that they effectively minimized the surveillance by only conducting it for the three days.

The presiding judge, Robert M. Gross, did not indicate how he or the other two judges, Melanie G. May and Cory J. Ciklin, would rule, but he made it clear to DeSousa what his main issue was with the state's case, that prosecutors were relying on a "textual" interpretation of the Fourth Amendment, as opposed to a long history of Supreme Court decisions that have established restrictions against law enforcement surveillance.

Gross seemed taken aback by DeSousa's contention that he and his colleagues should primarily consider the plain language of the Fourth Amendment. It says judges can issue warrants if police demonstrate there is probable cause of a crime and the warrants must specify the place to be searched and the people or property to be seized.

Gross told DeSousa he seemed to be ignoring numerous rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court expanding Fourth Amendment protections since the 1960s, including some that restricted electronic surveillance by police.

"You are getting us off on the wrong foot by focusing on the language of the Fourth Amendment when we should be focusing on the Supreme Court jurisprudence ... that is heavily weighted against you," Gross told DeSousa.

The 90-minute hearing included arguments on whether cameras were necessary; on whether the police violated the privacy of customers who simply received massages; and on the proper sanction if the defendants' rights were violated.

The attorneys for Kraft and the other defendants argued that police failed to minimize the privacy violations they committed by recording innocent customers, including women, who received legal massages.

"These cameras, that were put into private massage rooms where patrons would be undressing as a matter of course, they recorded everything," Kraft attorney Derek Shaffer said. He said Kraft "had the same reasonable expectation of privacy that any massage patron going to a licensed facility would be entitled.''

Attorneys also argued the cameras weren't necessary as police already had enough evidence to charge the spa owners, including bank records, website advertising, outside video surveillance and napkins containing bodily fluids retrieved from garbage bins.

The only proper punishment for prosecutors and police, they argued, is to throw out all recordings.

DeSousa argued that police and prosecutors need the recording to convict the owners of felonies. The owners must be shown receiving payments from the prostitutes and the only way to get that is to install cameras, he said.

He said detectives had to fully record all massages, because the sex acts happened at their conclusion and 95% of male customers received one. While no female customers paid for sex, they were few in number and to not record them could be seen as discriminating against men, he said.

DeSousa said even if the court finds police violated innocent customers' privacy rights, the Supreme Court has ruled that in most circumstances, only improperly seized evidence should be thrown out. Since Kraft, the other men and the masseuses were engaged in crimes, their recordings should be permitted, he said.

Kraft has never disputed the facts of the case, that he twice received sexual services at the Orchids of Asia Day Spa in Jupiter, Florida, on Jan. 19 and 20, 2019, but has fought the misdemeanor charges against him as a violation of his Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable search and seizure.

Kraft, who has a residence in West Palm Beach, Florida, visited the spa while police were conducting an investigation into what prosecutors said was suspected prostitution and human trafficking at several such Florida facilities.

No human trafficking charges were ever brought, and there was no evidence that the two women charged with servicing Kraft, Hua Zhang and Lei Wang, who were 58 and 39 at the time they were arrested, had been trafficked. Both had valid driver's and massage licenses.

"They knew that this was never a human trafficking case. Law enforcement knew it," Shaffer said.

After Kraft left the spa, police pulled over his Bentley under the pretense of a traffic violation and were able to identify him. The defense has argued that police failed to "minimize" their surveillance as required by the law, and that the lead Jupiter police detective, Andrew Sharp, deliberately misled the judge who approved the search warrant request.

Shaffer argued that if the video evidence is inadmissible, then evidence obtained from the traffic stop used to identify Kraft is also inadmissible.

Kraft was initially offered a deal that would have seen him pay a fine of $5,000, perform 100 hours of community service, attend a class about the negative effects of prostitution, and admit he would have been found guilty in court. In return, the evidence would have been permanently sealed and the case expunged from his record. But Kraft, worth an estimated $6 billion, chose to fight the charges, successfully arguing that Jupiter police did not have the right to install video surveillance in the spa. Kraft's attorneys have said they intend to see the case through trial, if necessary.

Even if Kraft is legally successful, NFL commissioner Roger Goodell has broad leeway to punish Kraft if he chooses, possibly with a fine or suspension.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Source: www.espn.com - NFL