Lost in Translation | History Today - 5 minutes read

In early May 2019, the Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Kono travelled to Moscow to meet with his Russian counterpart, Sergey Lavrov, to settle an old score. To this day, the Pacific powers have never signed a peace treaty following the Second World War. May’s meeting built on diplomatic efforts made earlier this year by the Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and the Russian President Vladimir Putin to resolve the longstanding dispute over a remote group of islands known as the Kurils. For 70 years, Russia has occupied the chain’s four southernmost islands, which Japan claims as part of its integral territory. February of this year marked the 25th time the two heads of state have met to reconcile the territorial tiff.

At the heart of this disagreement are the very things that are intended to prevent or resolve conflict: treaties. In the case of the Kuril Islands, several treaties and their subsequent translations have fuelled tensions. A look at other treaty translations – or mistranslations – from history illustrates why the Russo-Japanese conflict is so difficult to resolve.

Some treaty translations seem deceitful by design, crafted by powerful actors to exploit or extort. In these instances, treaties offer the offending parties a patina of legal legitimacy while acting badly, often to disastrous ends. In 1889, the Treaty of Wuchale granted Italy several of Ethiopia’s regions in exchange for money and arms. But a permissive verb in the Amharic version and a mandatory one in the Italian – the difference between a ‘could’ and a ‘must’ – led to a discrepancy over just how much autonomy Ethiopia had over its own foreign affairs. The Italians seized on the mistranslation and launched an ill-fated imperialist war on the turn of a verb.

Translations become particularly difficult when one party’s language lacks the word for a concept another party wants to describe. In New Zealand, the English text of the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi states that Maori chiefs would give total ‘sovereignty’ to the queen, while retaining their own ‘property’, but Maori society did not have these concepts. The words used in the Maori version of the treaty more accurately translate ‘sovereignty’ to ‘government’, and ‘property’ to ‘precious things’, which could include culture and language in addition to physical property. Deceit and an asymmetry of power undoubtedly played a role here as well, but these fundamental differences in language made it much easier.

Sometimes seemingly pedantic semantic differences can have serious consequences. In the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 242, the French text instructed Israel to withdraw from ‘des territoires’ (the territories) it occupied during the 1967 Six-Day War. The English text, however, merely read ‘territories’, removing the definite article and thus leaving ambiguous how much territory Israel should cede. Both French and English are official languages of the United Nations, raising the question of how various translations should be considered together to arrive at the clearest intended meaning.

These notoriously intractable conflicts leave little for the optimist in the case of the Kurils. Translation discrepancies across multiple treaties from over 100 years ago have given both Russia and Japan room to twist the narrative in their favour, pushing the Kuril Islands dispute beyond its 70th year.

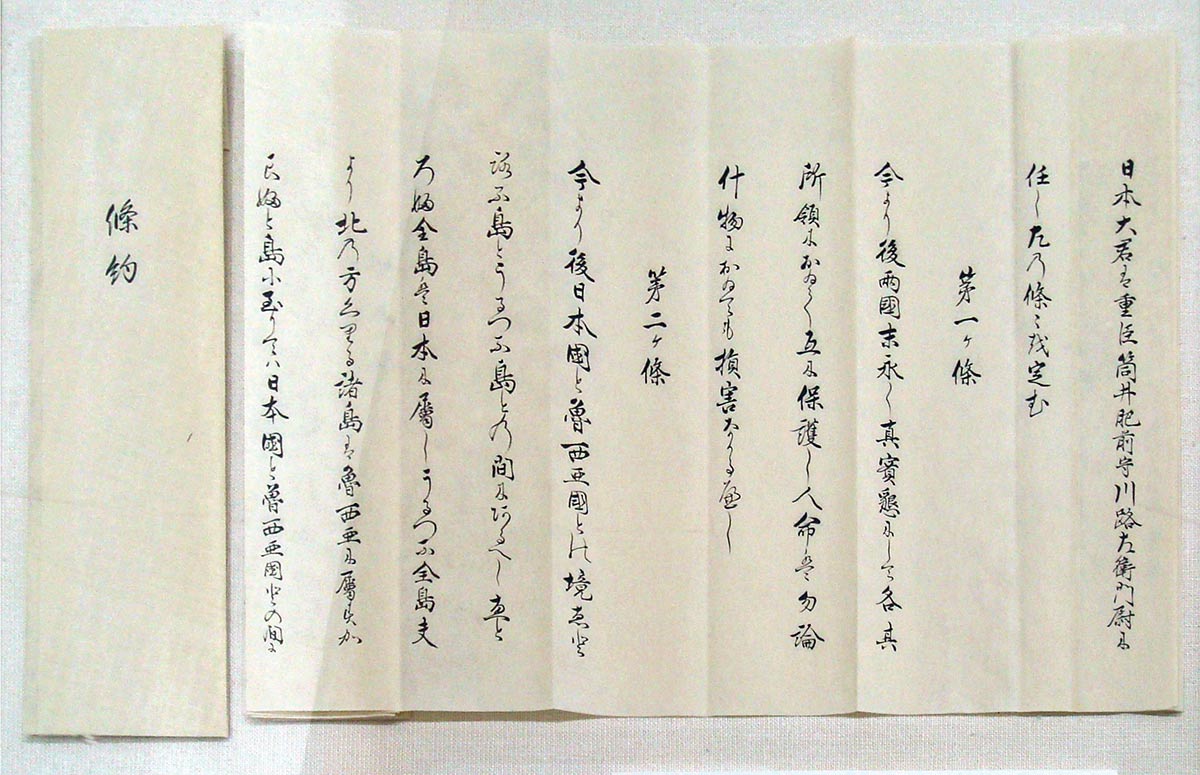

The disagreement stems from semantic differences in the Dutch and Japanese translations of the 1855 Treaty of Shimoda, which granted Japan the four southernmost islands in the Kuril Island chain and Russia the islands to the north. The difference is that, while the Japanese version simply states Russia holds sovereignty over the Kuril Islands to the north of the islands granted to Japan, the Dutch version (used by Russia) refers to the islands given to Russia as ‘the rest’ of the Kuril Islands, implying the Kurils extend beyond the specific islands under Russia’s control.

The small semantic difference implicating where the Kuril Islands begin and end took on outsized importance after the Second World War when Japan was compelled to relinquish ‘all right, title, and claim to the Kurile Islands’ upon signing the Treaty of San Francisco in 1951. By Russia’s logic, that article meant all the islands in the chain, including ‘the rest’ of the ones given to Japan under the Treaty of Shimoda, were now forfeited. But under Japan’s logic, the four southernmost islands never were the Kuril Islands. These four, Japan insists, are a separate island group called the Northern Territories, an integral part of Japan altogether outside the demarcation of the Kurils, which by definition have always been constrained to the northern islands Russia received under the 1855 treaty. What is and what is not considered the ‘Kuril Islands’ has prevented a formal postwar peace treaty between Russia and Japan ever since.

The drafters and translators of the Treaty could not have predicted that Japan would be compelled to give up rights to a territorial entity known as ‘the Kuril Islands’ nearly 100 years later, so a deceitful motive seems unlikely. Though it is difficult to prove whether the Japanese government of 1855 really believed the four islands in question were separate from the Kuril chain, it is possible that postwar Japanese governments have espoused this opinion for political gain at home and abroad, conjuring a historical basis to bolster its sovereignty claim.

Like the Treaties of Wuchale and Waitangi and UNSC Resolution 242, two different texts of the same treaty now exist, each deemed acceptable to its signatories at the time, but rejected by the other side today.

It remains unclear whether Russia and Japan will reach a consensus any time soon. The diplomatic questions over whether or not countries should be bound to treaties in foreign languages and which translation should take precedence when there is a discrepancy continue to confound. Even in an age of instant communication and abundant information, the written word is still a barrier to diplomacy.

Tyler McBrien is an Associate Editor and Prayuj Pushkarna is an Assistant Editor at the Council on Foreign Relations.