Cohn the Canary | History Today - 2 minutes read

There exists a subterranean world where pathological fantasies disguised as ideas are churned out by crooks and half-educated fanatics for the benefit of the ignorant and superstitious. There are times when this underworld emerges from the depths and suddenly fascinates, captures and dominates multitudes of usually sane and responsible people.

When the historian Norman Cohn wrote those words in his 1967 study of antisemitism, Warrant for Genocide, he did so in the shadow of the Holocaust and the Gulag, when human depravity had sunk to industrialised depths. The Vietnam War was at its height, Israel was about to win a crushing victory over its Arab enemies and the Soviet Union was firmly ensconced, trading blows with the West in a potentially catastrophic arms race. Yet despite such crises and conflict, a world carved out between two rival superpowers had a strange sense of stability, especially from a western perspective, its people made comfortable by a consumer boom. With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, a wave of near millenarian optimism capped the end of history and the victory of liberal democracy. Happy days.

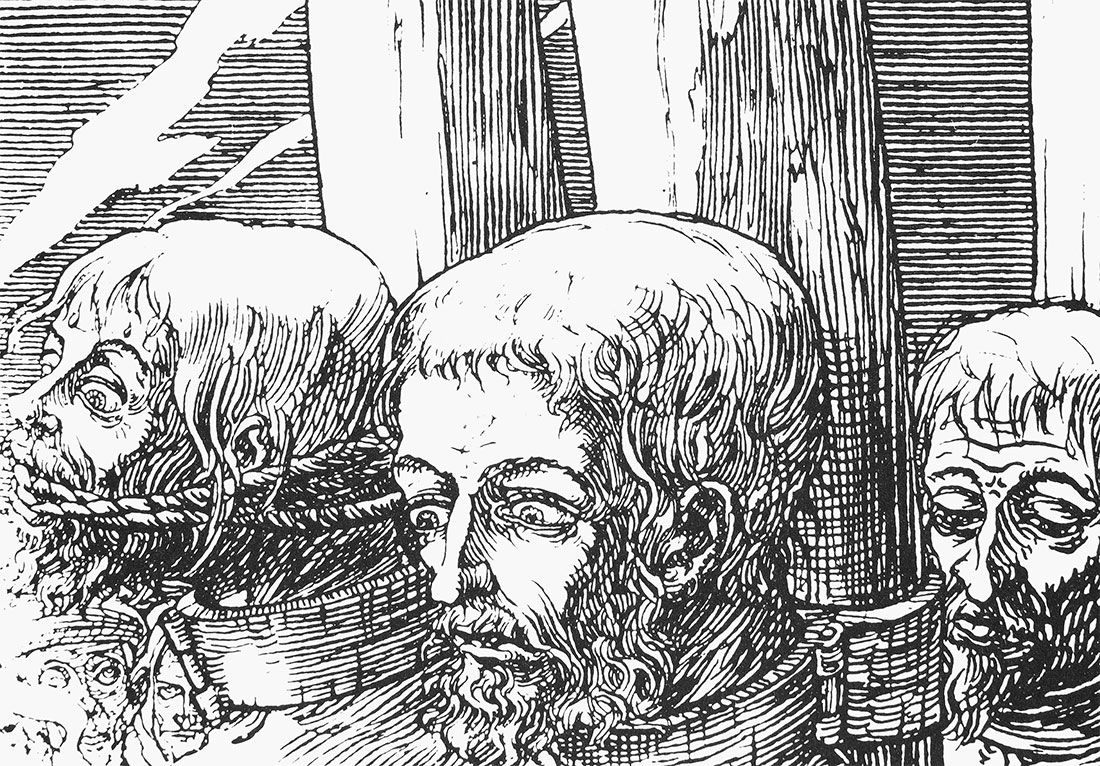

Norman Cohn, whose deep engagement with the grimmer corners of the past had vaccinated him against such panglossian fantasies, was open to criticism for his pessimism and sensationalism. Christopher Hill, for example, while praising Cohn’s Europe’s Inner Demons (1975) for its interrogation of the sources, was critical of his ‘obsessive fear of the urge to purify the world through the annihilation of some category of human beings imagined as agents of corruption and incarnations of evil’. Cohn’s description of the Anabaptists of Münster was thought lurid, a criticism with, perhaps, greater purchase. Or so it once seemed – before we witnessed the crucifixion and beheading of Yazidis, Christians and other religious and ethnic minorities by ISIS; before the massacres of Utøya and Christchurch. It is not a good sign when Cohn’s work takes on new relevance.