Opinion: How paranoia in presidential politics went mainstream - 5 minutes read

(CNN) The 1950s are often portrayed as a placid decade of peace, prosperity and "Happy Days." You might even think that presidential elections were courtly affairs back then -- very different from the current bitter, anxious contest between President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden.

(CNN) The 1950s are often portrayed as a placid decade of peace, prosperity and "Happy Days." You might even think that presidential elections were courtly affairs back then -- very different from the current bitter, anxious contest between President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden.Think again.

The 1950s was no gentle era. The Cold War burned red hot. The Korean War took the lives of more than 34,000 American soldiers between 1950 and 1953.

At home, the Red Scare hung in the air as Republican Sen. Joseph McCarthy launched a series of investigations fueled by false accusations of Communist subversion in government. Abroad, the United States used both overt force and covert action to confront and suppress leftists that Washington considered threats.

And in the midst of that, the Civil Rights movement gathered momentum as it confronted systemic racism and segregation.

The presidential election of 1952, though not quite so fraught and anxious as the 2020 contest, reflected these tensions and divisions in American public life. And it was that year's race, between General Dwight Eisenhower and the one-term Governor of Illinois Adlai Stevenson, that helped develop the deep partisanship and political fearmongering we see today.

At the time, Eisenhower was a newcomer to politics; he'd only just announced his Republican party affiliation. When he launched his presidential campaign, he was universally well-known as the man who led the successful invasion of Western Europe against Hitler's Nazi armies.

Still, Eisenhower did not run on his reputation as a non-partisan consensus-builder. He ran for president as an outsider, a man who could to "fix the mess in Washington," as he put it

By instinct a conservative, Eisenhower pulled no punches on the 1952 campaign trail. He criticized outgoing President Harry Truman for weak leadership during the unpopular Korean War. He claimed that 20 years of Democratic control during the presidencies of Franklin Roosevelt and Truman had led to a bloated, centralized government. And he also stooped to using a growing fear of communism as a political tool to gin up anxiety about the Democrats.

The FBI had known that a small number of Communist sympathizers had been at work in the US government, passing secrets to the Russians. Wisconsin Sen. McCarthy had seized upon these kernels of truth to fabricate a full-blown conspiracy about a vast web of Communist spies in Washington.

McCarthy could never back up his charges , and Eisenhower privately disliked the popular Republican. But in an election year, Eisenhower chose not to publicly criticize McCarthy and instead piled on, charging the Democrats with being "soft" on Communist subversion in the United States. Ike described Roosevelt's New Deal as something akin to socialism — "beyond which," he believed, "lies total dictatorship." And he insinuated that the Communist forces had become emboldened during the Truman years and were now on the march across Asia and Europe.

Americans, Eisenhower seemed to suggest, needed a general to take charge of the Cold War. To save democracy, he claimed, Democrats had to be kicked out of the Oval Office.

Harry Truman wasn't running for re-election, but he decided to enter the fray to defend his record. He decried the "wave of filth" spread by the Eisenhower campaign. He mocked Ike as a man out of his depth, a once-noble figure who had "surrendered" to the far right of the GOP and let himself be used "as a tool for others."

As these two heavyweights traded charges, 1952's actual Democratic candidate, Stevenson, gave eloquent speeches about the need to follow higher ideals in politics. He made a good effort, but he had no chance. Ike won in a landslide in 1952, winning all but nine states.

Yet even so, 1952 was a turning point of sorts. It brought into the mainstream of presidential politics what the historian Richard Hofstadter would later identify in a 1964 essay as "the paranoid style." Hofstadter had Joe McCarthy in mind when he described a strain in American public life characterized by "heated exaggeration, suspiciousness and conspiratorial fantasy."

Although Eisenhower would go on to become a much-loved president known for his moderation and integrity, his campaign in 1952 had a whiff of McCarthyism about it. On the road to his election win, Ike coasted along on McCarthy's charges against Democrats of betrayal at the highest levels of government. And even though he disavowed McCarthy's baseless accusations of treachery , later using presidential power to bring an end to McCarthy's reign, Ike still campaigned alongside the red-hunting Wisconsin senator. Both won their races in that pivotal year.

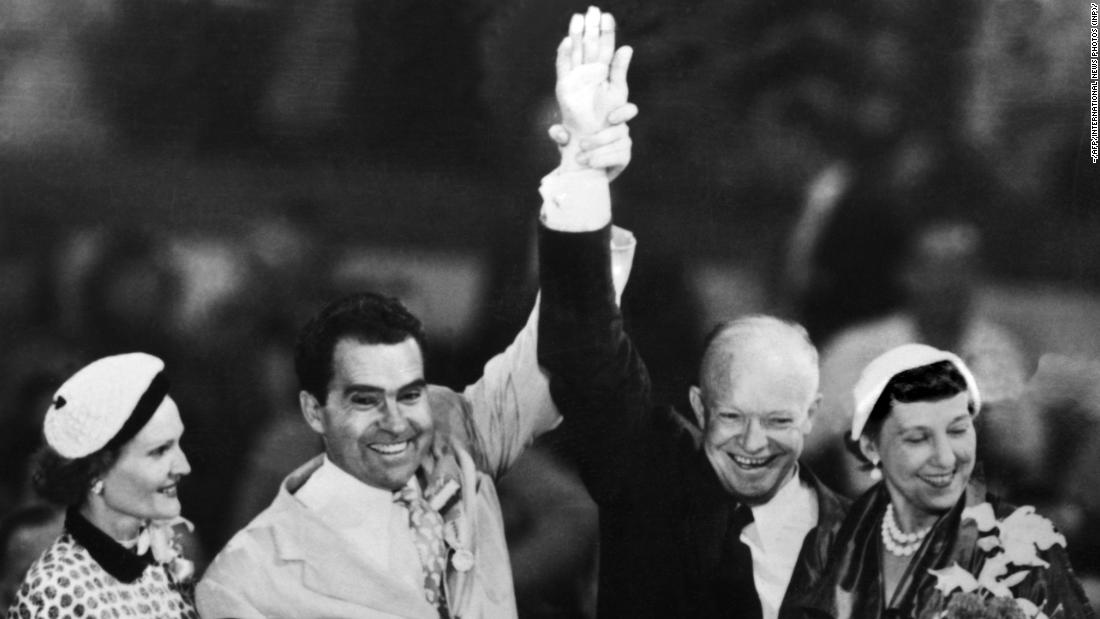

Charges of disloyalty and subversion; tagging the Democrats with the dreaded term "socialism" to conjure up a nightmare police state; encouraging populist backlash against the federal government that allegedly was smothering freedom in America — these were tropes that Eisenhower and his running mate Richard Nixon deployed throughout their run for the White House.

Although Ike dropped this kind of politicking once he took office, many in his party — notably Nixon and later Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona — watched 1952 carefully. And they drew the conclusion from Eisenhower's success in 1952 that the paranoid style, inducing fear and anxiety in the electorate rather than hope and optimism, works.

Source: CNN

Powered by NewsAPI.org