Memento Mori | History Today - 4 minutes read

The past and the present talk to each other continually. As a historian, I tend to obsess over this communication. Two weeks of broken central heating in winter a few years back was uncomfortable but, at least, an insight into how people lived historically. For me, then, lockdown evoked the past in several profound ways, connecting me to a shared humanity through time from which our society has tried to distance itself.

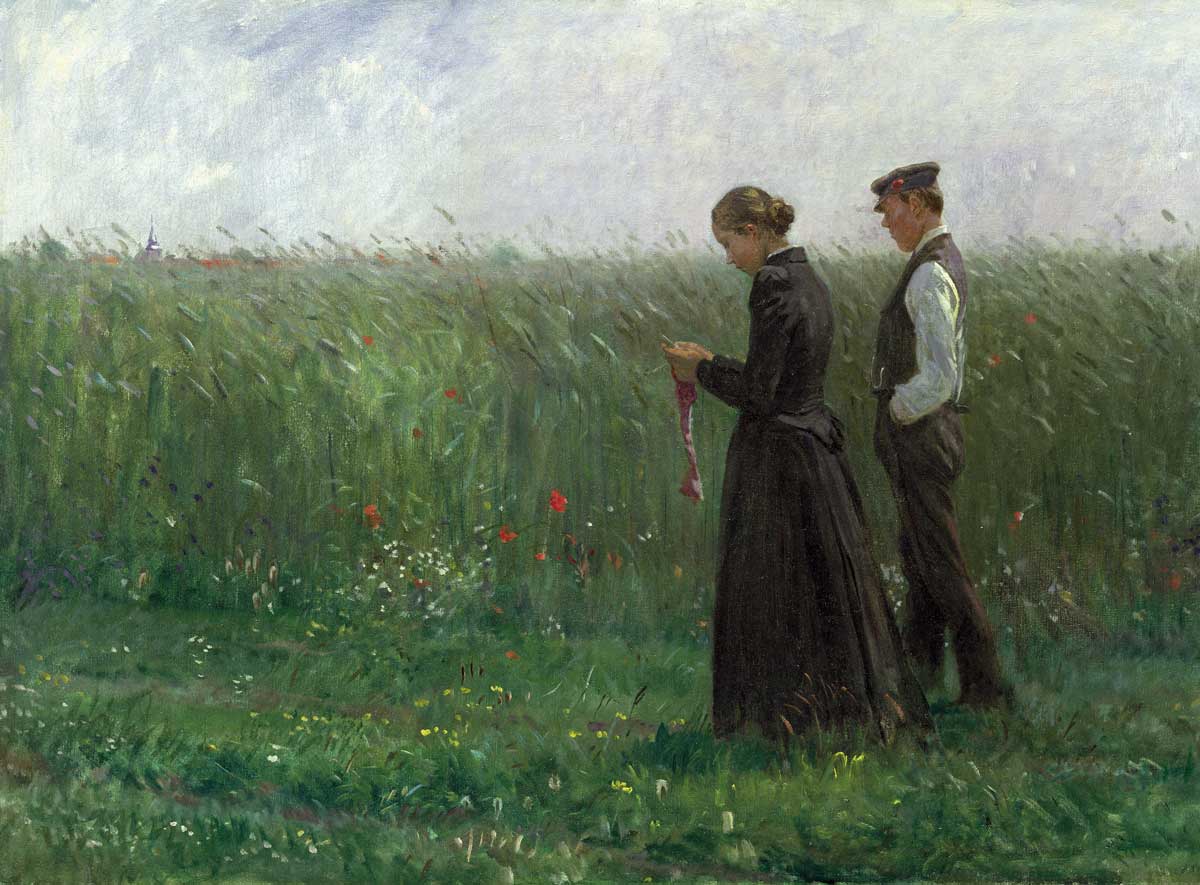

Slowing down was a shock. It was strange that for a few months, I – like most of us – didn’t travel by plane, car, train, tram or bus. I moved no further and no faster than my feet could carry me. My geographical circle shrank, though I found myself walking further and more often. In so doing, I, like so many others, was recovering an experience of past lives. Adam Nicolson’s beautiful biography of Coleridge and Wordsworth’s year in the Quantocks – Coleridge probably invented fell-walking as a pastime, while Wordsworth had previously completed a 3,000-mile walk of the Alps – evokes how commonplace walking was in the late 18th century. People of all social ranks walked to visit each other; they walked to run errands and deliver news. Returning soldiers walked from the ports of arrival to their homes. Walking between cities to stay with friends could be preferable to a long, jolting ride in a cart. People rambled for pleasure, to think and to talk, and not just in fine weather: they traipsed through rain and trudged through snow. In remembering the joys and uses of Shanks’ pony, we are discovering what our ancestors knew.

Walks have been an escape from the home, often housing both domestic life and much of our productive activity, the two jostling and colliding with each other. The preparation of meals seems to be more constant than before; for many, children have been underfoot, alongside, ever-present in this new iteration of home life. But working from home is nothing new. Before the Industrial Revolution, the household workshop was common. The same space was used for both residential life and economic production. Households in the 16th to 18th centuries tended to be, like ours, relatively small: nuclear families with only occasional members of extended kin in residence, although about a third of households also included a normally adolescent servant. Many households pursued an artisanal trade in which all might participate, but even besides that, the home was a place of work: caring for cattle, sheep and poultry; tending herbs and vegetables; churning butter and making cheese; boulting, baking, malting and brewing; as well as cooking and tending children. We may wield keyboards more than boulting sieves, but the construction of a rift between ‘work’ and ‘home’ is recent. Trying to find ways to meet the demands of both confronts us with choices that are not unique in time.

Our predecessors were also much more aware of something that, before coronavirus, we had tried to banish from our visible world: they knew that they, and the people they loved, would die. Mortality rates in early modern England were two or three times our pre-Covid norm and preachers urged people to be ready for death at all times. ‘In this world we are but tenants-at-will and no man has a lease of his life for term of years’, wrote Robert Hegge in 1629. Therefore, the centuries before ours created a culture that meditated on death, marked death with rituals and took seriously the ars moriendi or art of dying well.

Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s great historical novel, The Leopard, evokes this: as he lies dying in 1883, the Sicilian prince Don Fabrizio Salina hears the tinkling arrival of the priest bearing the last sacraments. It comforts him and reminds others of death’s presence. Earlier in the novel, his carriage had stopped to allow another priest bearing the ciborium to pass and Don Fabrizio and his companions had knelt on a society in which ‘everything ... goes on as if nobody dies anymore’, as Philippe Ariès put it.

Terrified by what we can’t control, we have set out to whizz past, compartmentalise and ignore what we do not wish to contemplate. This pestilence has forced us to become much more like our forebears: to face the messiness and meaning of life – and death.

Suzannah Lipscomb is Professor of History at the University of Roehampton and author of The Voices of Nîmes: Women, Sex and Marriage in Early Modern Languedoc (Oxford, 2019).

Source: History Today Feed