We are Family | History Today - 6 minutes read

Late in August 1179 the king of France, Louis VII, crossed the Channel and landed at Dover. There he was met by Henry II, the man now married to Louis’ first wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, father-in-law to one of his daughters, Margaret, and custodian of another, Alice. Escorted by Henry, Louis and his retinue travelled to Canterbury to the shrine of Thomas Becket, an archbishop who had spent years in exile in France before he was murdered in his own cathedral by men allegedly acting on Henry’s orders. There, Louis raised heartful prayers for the swift recovery of his only son and heir from a fever that had left 14-year-old Philip close to death. Contemporary chroniclers were quick to point out that no king of the French had ever made such a trip to England. Yet although Louis’ visit was unprecedented, the intertwined nature of the royal families of France and England was well established, as Catherine Hanley’s new book ably demonstrates.

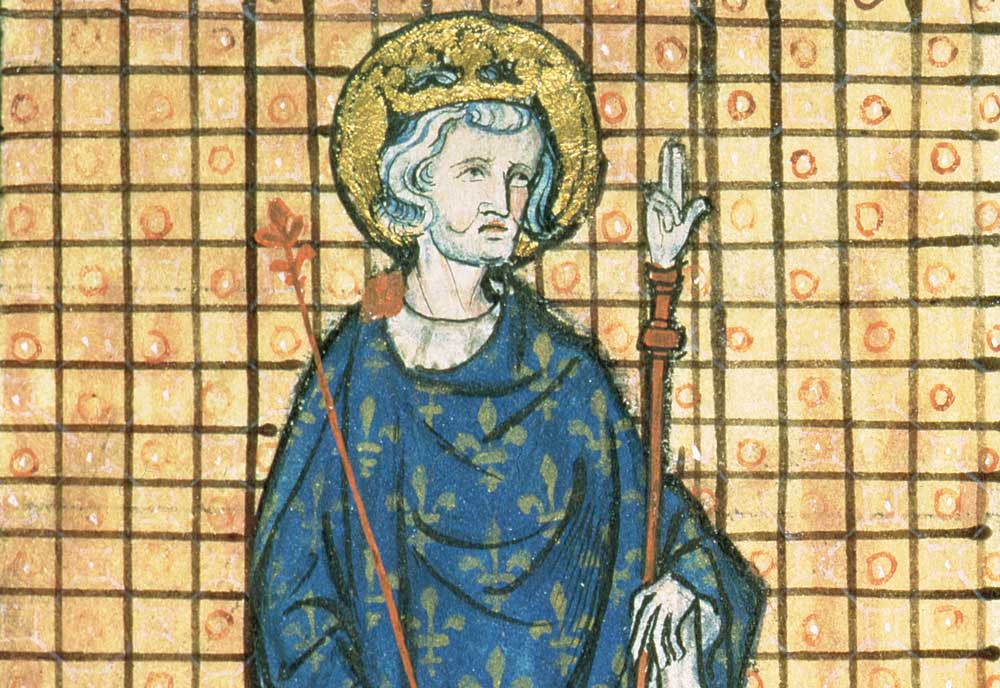

Interactions between the ruling families of England and France had a long history pre-dating 1100. Exiled English princes including a future king, Edward the Confessor, had met and attested charters alongside the French ruler in the 1030s. One of the claimants to the English throne in 1066, Edgar Ætheling, was almost certainly the first cousin of Philip I of France. And then there was the longstanding issue of the Vexin, a hotly contested territory on the Norman-French border. Consequently, although 1100 saw the arrival of a shocking letter from France at the English king’s Christmas court, requesting that Henry I detain and imprison Louis, Philip I’s eldest son, who was in attendance, Hanley’s claim that it was the ‘first moment of real, dramatic interaction between the dynasties’ downplays a much lengthier story of Anglo-French royal relations.

Nonetheless, interactions between the ruling dynasties became very common during the 12th and 13th centuries. From marital alliances uniting the houses, to open warfare pitting relatives against each other; from tense meetings on bridges (as between Henry I and Louis VI over the Epte on the French-Norman border in 1109), to collective mourning at family funerals. Parts of the story Hanley relates will be familiar, such as Louis VII’s support for Henry II’s sons, ‘the devil’s brood’, in rebelling against their father, or Philip Augustus’ spectacular victory at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214. Other events may surprise and Hanley’s eye for narrative detail vividly brings them to life, as in the account of a queen of France, Isabelle of Hainaut, who had the political acumen to beg public favour, barefoot, on the streets of Senlis in protest at her husband’s attempts to divorce her. There is also the undoubtedly apocryphal but delightful tale of Blondel, a travelling minstrel who located Richard I by journeying from castle to castle singing a song known only to the two of them, until one day he heard the imprisoned king’s dulcet tones joining in the tune.

Children were central to many of the interactions that Hanley covers. Their deaths could alter plans for royal succession and irrevocably shift the fortunes of either dynasty. When, in 1120, William Adelin drowned in the White Ship disaster, Henry I’s loss of his adolescent son and heir brought Louis VI a distinct political advantage. The French king resurrected his support for Henry’s nephew, William Clito, as the rightful successor to the English throne. Peace between the realms was often settled by the betrothals or marriages of young girls and boys, as in the Treaty of Montreuil in June 1299, which agreed a union between Edward, the 15-year-old son of the English ruler, and Isabelle, the four-year-old daughter of the king of France. Royal children were the cornerstones of dynastic power.

Medieval kings were rarely kind to those who got in their way, often leaving devastated lives and communities in their wake. Entire towns were burned to the ground to facilitate royal escapes, as when Louis VII left Verneuil in 1173 or Henry II fled Le Mans in 1189. Workers were deprived of their crops to feed an army or simply to prevent the other side from seizing the harvest themselves. Crews of sailors trying to make a living through trade were hanged by their own king, Richard I, in the harbour of St Valéry in 1197 for daring to defy royally imposed sanctions. Hanley brings some of these stories to the fore, showing how innocent people often paid the brutal price for their ruler’s actions. While the harrowing fate of the citizens expelled from Château Gaillard – starving to death while trapped between the French army and the impenetrable fortress during the harsh winter of 1203-04 – may seem far removed from the modern world, the root cause is all too familiar. Political elites who believe the rules they impose on others do not apply to themselves; rulers who exploit their personal connections and use a kingdom’s resources to pursue their own goals.

Two Houses, Two Kingdoms is, in many respects, a conventional political history, following a strict chronology with a focus on royal power, military strategy and warfare. Nearly five pages are devoted to the events of the Battle of Lincoln on 20 May 1217, for example, despite no representative of either the French or English ruling families having been present. By contrast, the nine weeks that Henry III spent in and around Paris visiting Louis IX’s court from November 1259 to January 1260 receive much less attention, even though the meeting of the two kings was the culmination of efforts to bring lasting peace between their realms. This is an eminently readable book, nonetheless, and the attention paid to women and children as crucial participants in dynastic rule is refreshing. For those seeking an overview of the relationship between France and England that examines the fluctuating fortunes, both personal and political, of their ruling families, Hanley’s book is the place to start.

Two Houses, Two Kingdoms: A History of France and England, 1100-1300

Catherine Hanley

Yale University Press 480pp £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Emily Joan Ward is the author of Royal Childhood and Child Kingship: Boy Kings in England, Scotland, France and Germany, c. 1050-1262 (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Source: History Today Feed