Less Than Happy? Blame Jefferson. - 8 minutes read

Less Than Happy? Blame Jefferson

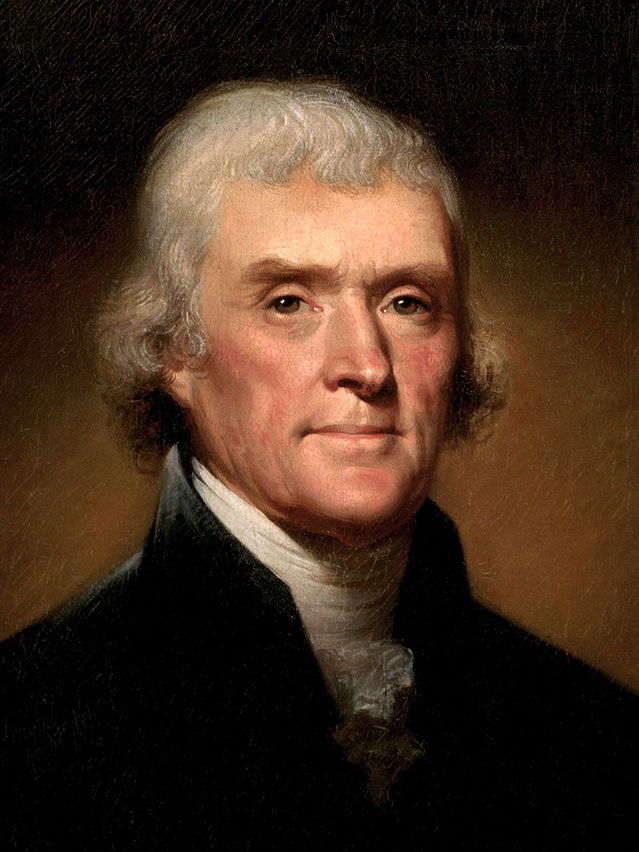

Less Than Happy? Blame JeffersonIs your quotient less than you think it should be? Consider blaming Thomas Jefferson, as it was he who penned the words “the pursuit of happiness” in the Declaration of Independence in 1776. A reasonable argument could be made that Jefferson’s pithy phrase set in motion a nearly two-and-a-half-century chase for happiness in this country that many Americans have found to be a losing proposition. Expectations for happiness have far exceeded its realities, leading to frustration and disappointment when life offers lemons rather than lemonade.

The history of the four-word phrase is an interesting one. Historians have paid special to Jefferson’s choice of words or, more accurately, his bold and surprising decision to use the word “happiness” in the document. The phrase is “as fundamental, as baffling, as confused and as interesting an idea as ever appeared in a state paper,” thought Howard Mumford Jones in 1952. While Jefferson is often credited for originating the phrase, it was actually a Virginian colleague of his, George Mason, who is widely acknowledged as having planted the seed. “Pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety” was a basic human right, Mason declared at the Virginia Convention of May 1776, with that phrase included in the preamble of that state’s constitution. Jefferson obviously found the phrase compelling but edited it to concentrate its linguistic impact, and attached it to the other inalienable rights of “life and liberty” (here borrowing from the English philosopher John Locke, who some consider to be “the grandfather of the American Declaration of Independence”).

Over the next century, most states adopted versions of “the pursuit of happiness” in their own constitutions, further weaving the concept into the American quilt. Happiness is thus a literally stated goal of the government in the United States, a remarkable thing from a historical sense that reflects the transcendent vision of the Founding Fathers. “All human beings may come equipped with the pursuit-of-happiness impulse-- the urge to find lusher land just over the hill, fatter buffalo in the next valley,” observed Jeffrey Kluger, Alex Aciman, and Katy Steinmetz in 2013, “but it’s Americans who have codified the idea, written it into the Declaration of Independence and made it a central mandate of the national character.” “Human equality and the liberty to build a happy life are inextricably linked in the cadences of the Declaration, and thus in America’s idea of itself,” echoed historian Jon Meacham that same year.

William Gorman and Mortimer Adler have pointed out that Jefferson’s interest in adopting the phrase went far beyond its rhetorical power. Liberal philosophers of the 17th and 18th centuries like John Locke considered “property” to be one of an individual’s fundamental rights, making that term the more likely one for Jefferson to have employed. Jefferson recognized that “happiness” was a more universal and nobler concept than “property,” however, and that the pursuit of the latter was ultimately about the pursuit of the former. Happiness went far beyond the ability the ownership of property (or related terms such as “possessions” or “estate”), the Founding Fathers understood, something many Americans would learn a couple of centuries later when their materialistic ways did not make them appreciably happier people. “It was a remarkably succinct expression of the American Dream, a confident look to the future rather than a backward nod to John Locke,” suggested Timothy J. Shannon in 2016, thinking that the phrase “remains foundational to how we define ourselves as a nation.”

While Jefferson’s choice of words was undoubtedly brilliant and courageous (if not entirely original, which he never claimed it to be), treading into the waters of happiness invited the ambiguity that has always been associated with the word. Rather than be limited to the opportunity to pursue one’s personal interests without interference by church or state, which was perhaps Jefferson’s intent, “the pursuit of happiness” became open to an infinite array of meanings. Regrettably, the phrase could be interpreted as endorsing one’s self-interest at the expense of others, certainly not what the man had in mind. Was Jefferson being intentionally inexplicit in opting for “happiness” over “property,” allowing for Americans to decide for themselves what the word meant for them? Or did he just not anticipate that the term would prove to a major source of perplexity, even for constitutional scholars? Going further, did Jefferson mean individual happiness or a collective version designed to serve the public good? No one knows the answers to such questions, leaving the matter as one of the great puzzles in American history.

If the meaning of the word itself is unclear, there is no question that the Founding Fathers recognized how important happiness was to an individual and to society as a whole. “For the Founders, ‘happiness’ was the obvious word to use because it was obvious to them that the pursuit of happiness is at the center of man’s existence,” Charles Murray wrote in 1988, locating the phrase firmly at the heart of the fundamental American idea. Again, however, it was the role of government to enable happiness among its citizens, the Founders firmly believed, as only that would entice people to consent to be governed. Infused by the thinking and values of the Enlightenment, the Declaration of Independence propelled the trajectory of happiness, canonized its pursuit, and, ultimately, turned it into a primary ambition among most Americans.

Over the next two centuries and change, Jefferson’s phrase spawned into such cultural artifacts as the “Happy Birthday” song (1926), the smiley face (1963), McDonald’s Happy Meal (1977), and the full-fledged culture of happiness that we have today. Beyond all the how-to’s, instructions in and expressions of happiness are nearly everywhere you look today, from Muzak to the television laugh-track to overtly cheerful salespeople to anything bearing the Disney brand. Despite all this, however, surveys over the years have consistently shown that Americans have never been particularly happy people, leading one to wonder if our perpetual search for happiness is a futile one. Our competitive and comparative American Way of Life has not proven to be an especially good formula to generate high levels of happiness, we might conclude, with external signs of success unlikely to produce appreciably happier people. Rather, it is enjoying the little things in life that tend to lead to happiness, research shows, with focusing on the present another good strategy to become a more joyful person. Should Jefferson have used “live in the moment” instead of “the pursuit of happiness” when charting out his vision for America and Americans?

Source: Psychologytoday.com

Powered by NewsAPI.org

Keywords:

Thomas Jefferson • Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness • United States Declaration of Independence • Reason • Argument • Thomas Jefferson • Phrase • Set (mathematics) • Happiness • Proposition • Happiness • Reality • Life • Lemonade • History • Word • Phrase • Choice • Word • Decision-making • Word • Happiness • Phrase • Fundamentalism • Idea • Howard Mumford Jones • Thomas Jefferson • Phrase • Virginia • George Mason • Happiness • Human rights • Fifth Virginia Convention • Phrase • Preamble • Constitution of Michigan • Thomas Jefferson • Phrase • Linguistics • Natural and legal rights • Life • Liberty • Kingdom of England • Philosopher • John Locke • United States Declaration of Independence • State (polity) • Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness • Quilt • Government • United States • Object (philosophy) • Sense • Transcendentalism • Visual perception • Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness • American bison • Jeffrey Kluger • United States Declaration of Independence • Mandate of Heaven • Egalitarianism • Liberty • United States Declaration of Independence • History • Jon Meacham • William Gorman • Mortimer J. Adler • Thomas Jefferson • Phrase • Rhetoric • Power (social and political) • Liberalism • Philosopher • Century • John Locke • Property • Individual • Human rights • Time • Thomas Jefferson • Thomas Jefferson • Happiness • Universal (metaphysics) • Concept • Property • Happiness • Ownership • Property • Personal property • Founding Fathers of the United States • Materialism • Happiness • Freedom of speech • American Dream • Future • John Locke • Claude Shannon • Phrase • Foundationalism • Word • Happiness • Ambiguity • State (polity) • Thomas Jefferson • Intention • Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness • Infinity • Meaning (linguistics) • Phrase • Ethical egoism • Mind • Thomas Jefferson • Happiness • Property • Time • Constitutionalism • Scholasticism • Thomas Jefferson • Individualism • Happiness • Collectivism • Public good • Founding Fathers of the United States • Individual • Society • Holism • Founding Fathers of the United States • Logos • Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness • Centrism • Existence • Charles Murray (political scientist) • Phrase • Fundamentalism • Idea • Government • Happiness • Citizenship • Founding Fathers of the United States • Person • Government • Thought • Value (ethics) • Age of Enlightenment • United States Declaration of Independence • Happiness • Biblical canon • Phrase • Smiley • McDonald's • Happy Meal • Happiness • Background music • Laugh track • The Walt Disney Company • Value (ethics) • Happiness • Life • Happiness economics • Human • Thomas Jefferson • Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness • America and Americans •