Barbados and the End of Monarchy - 9 minutes read

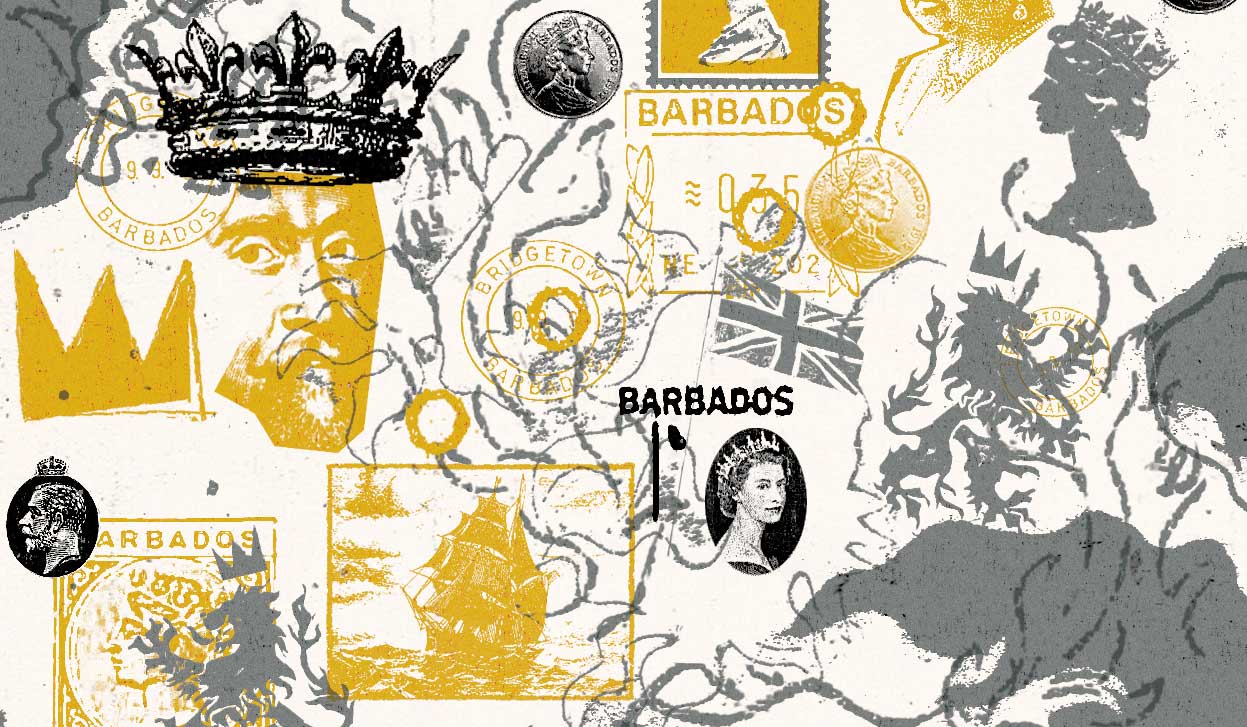

As a child in the 1960s in Barbados, the symbols of the monarchy and of the island’s connection with Britain were so omnipresent that one took them for granted. Portraits of the Queen and Prince Philip adorned the front covers of our exercise books. The Queen appeared on postage stamps and there was a crowned royal cypher on every red-painted letter box. Occasionally, one might catch a glimpse of a car with nothing except a large silver crown on its black number plates, identifying it as the official vehicle of His Excellency the Governor, the local representative of royal authority. The coins we used had the Queen’s crowned head on one side and, while the designs were different, the one cent and two cent coins were the same size, weight and value as the older British halfpennies and pennies that still turned up in our change, with portraits of British monarchs going back to Queen Victoria.

Royal portraits on coins suggested connections with the past, but any closer examination of the history Barbadians were offered in the 1960s was very selective. Even towards the end of the decade, a little after independence, when I was a pupil at Harrison College, one of the island’s leading secondary schools, I learnt more about the foibles of King James I than I did about anti-slavery and anti-colonialist figures such as Toussaint L’Ouverture or Henri Christophe. We all knew, however, how the good ship Olive Blossom had put in to an apparently uninhabited Barbados in 1625 and how Captain John Powell had left an inscription somewhere near what became Holetown, proclaiming ‘James K[ing] of E[ngland] and this Island’. Textbooks still current in my schooldays, such as the three-volume West Indian Histories by Edward W. Daniel, originally published in the 1930s and several times reprinted, or the slightly later A Short History of the British West Indies by H.V. Wiseman (1950) described the ending of colonial slavery as if it were almost exclusively the result of the benevolence of British evangelicals and downplayed the significance of enslaved resistance. This approach was echoed in popular culture, with one of the oldest known Barbadian folksongs attributing freedom to royal intervention:

God bless de Queen fuh set we free,

Hurrah fuh Jin-Jin;

Now lick an’ lock up done wid

Hurrah fuh Jin-Jin.

The reference would appear to be to 1838 and the ending of the apprenticeship system, a sort of half-freedom that still tied the formerly enslaved to their ex-masters, not to Emancipation in 1834 and the official ending of colonial slavery. ‘Jin-Jin’ is conventionally interpreted as Queen Victoria, possibly from the ‘Regina’ in the Latin version of the Queen’s titles, which would have been familiar from legends on our coins.

The road to independence

Yet in many ways all this was a façade. Even by the 1950s, with the introduction of a full ministerial system of government in Barbados in 1954, the role of the governor had become largely ceremonial, with the country’s internal affairs being run by local politicians chosen by an electorate based on universal adult suffrage. Barbados’ move to complete independence on 30 November 1966 was the logical outcome of deep-rooted political developments. Since 1639 there had been a local parliament in the shape of the House of Assembly, which frequently engaged in disputes with the Governor – the representative of royal, that is, British, authority – in defence of local interests. The modern historian will note that for much of its history the House of Assembly was elected on an extremely restricted franchise and represented only the interests of white Christian male landowners, who were often the most zealous in claiming their liberties as British subjects when they were opposing some policy that the British government was attempting to impose on them.

In 1831 the franchise was extended to all those who met the property qualifications among the island’s Jews and ‘Free Coloureds’ (that is, persons of African descent who were not enslaved) and thereafter a painfully slow series of incremental changes gradually extended it still further until by 1950 all adult men and women had the right to vote. This process was accelerated towards its end by the growth of trade unions and political parties from the 1920s onwards.

The Independence Constitution provided for Queen Elizabeth to continue as head of state after independence, not as Queen of the United Kingdom, but as Queen of Barbados, though diplomats representing the new nation sometimes found themselves challenged to explain the difference to representatives of republics. The continuance of the monarchy was undoubtedly a concession to the more conservative views of a significant proportion of the population. A government commission in 1979 recommended the retention of the monarchy, reporting that this was the preference of the population as a whole. This was not a uniquely Barbadian phenomenon: of Britain’s former Caribbean colonies, only Dominica became a republic at its independence in 1978.

Why now?

Barbadian public opinion was certainly influenced by perceptions of the Guyanese experience. Guyana retained the Queen as head of state at independence in 1966, but became a republic in 1970. Many Barbadians associated the republican system in Guyana with the rule of Forbes Burnham, the country’s prime minister, who became executive president following further constitutional change in 1980. Burnham was seen as a virtual dictator whose policies were economically disastrous, a view certainly propagated by the many Guyanese of partly Barbadian ancestry who were able to relocate to Barbados and claim citizenship there.

Nevertheless, the government of the Barbados Labour Party set up another Commission in 1996, which reported in 1998 in favour of a transition to a republic, a view later adopted by the other main party, the Democratic Labour Party. While the British media has expressed surprise at Barbados removing the Queen as head of state, the question is really why it took until 2021 for this to happen.

A large part of the answer is that it has been the result of a gradual process of cultural change. Many Barbadians have family connections with Britain, British tourists continue to be important to the island’s economy and there are other trading links. Nevertheless for several decades North American cultural influences have been more significant.

At the same time, new trends in academic work on Caribbean history gradually made their way into public consciousness, a process facilitated by the abandonment of a reliance on external British systems of educational standards and the establishment of regional institutions such as the University of the West Indies (1948) and the Caribbean Examinations Council (1972). This drew attention to aspects of the past including the details of the transatlantic slave trade and colonial slavery, the frequency and importance of acts of resistance among the enslaved population and the significance of African elements in Caribbean and Barbadian popular culture.

What’s new?

None of this was entirely new. Even in 1936 Edward W. Daniel wrote of ‘the bad old days of slavery’ and pointed out that Charles II and James II had shares in the Royal African Company. The ground-breaking Capitalism and Slavery by Eric Williams (later Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago) was first published in 1944, arguing for the importance of colonial slavery and sugar plantations in the growth of the capital which fuelled Britain’s Industrial Revolution. From the 1970s, however, a new generation of locally and regionally educated cultural activists worked to diffuse this attitude among the wider Barbadian public.

A more critical view of the British aspects of the island’s past was inevitable. Some of this was practical. Many people, for example, questioned why independent Caribbean countries retained Britain’s Judicial Committee of the Privy Council as their highest legal Court of Appeal, something given repeated attention by judgments in which the Privy Council appeared to be attempting to abolish the death penalty by stealth (e.g., the Pratt and Morgan case, 1993), even though there was widespread popular support in the Caribbean for retaining the death penalty for murder. Barbados was one of the parties to the 2001 agreement to establish the Caribbean Court of Justice, which was formally inaugurated in 2005, replacing the Privy Council for the participating states.

Others were more symbolic. A number of Barbadian historical figures were officially declared to be National Heroes in 1998 and the following year what had been Trafalgar Square in Bridgetown was renamed National Heroes Square. Since the 1970s there had been calls for the removal of the statue of Horatio Nelson that had stood in Trafalgar Square from 1813, having been paid for by many Barbadians through public subscription. At first, the statue was merely seen as an undesirable relic of colonialism, but by 2020, after the Black Lives Matter protests in the US, Nelson was specifically targeted as a white supremacist and an active supporter of the slave trade.

These claims have been controversial as they are based on a letter which Nelson wrote that can be shown to have been altered after his death, but the damage was done. Nelson in Barbados had become a powerful symbol of a colonial past which could only be viewed in a negative light.

Back to the future

By the time Nelson was finally removed from National Heroes Square on 16 November 2020, the government of Barbados had announced that the country would become a republic at the 55th anniversary of independence. This came into effect on 30 November 2021.

What happens next remains to be seen. Just days after the celebrations, the government announced plans for a Transatlantic Slavery Museum, including a new home for the country’s archives, to be built at Newton Plantation, the location of one of the few slave burial grounds discovered and scientifically studied in the Americas. With this, the Republic of Barbados will inaugurate a new era of official support for heritage on an unprecedented scale.

John T. Gilmore is Reader in the Department of English and Comparative Literary Studies at the University of Warwick and co-author of A-Z of Barbados Heritage (Miller Publishing, 2020).

Source: History Today Feed