Ukrainian Tales | History Today - 9 minutes read

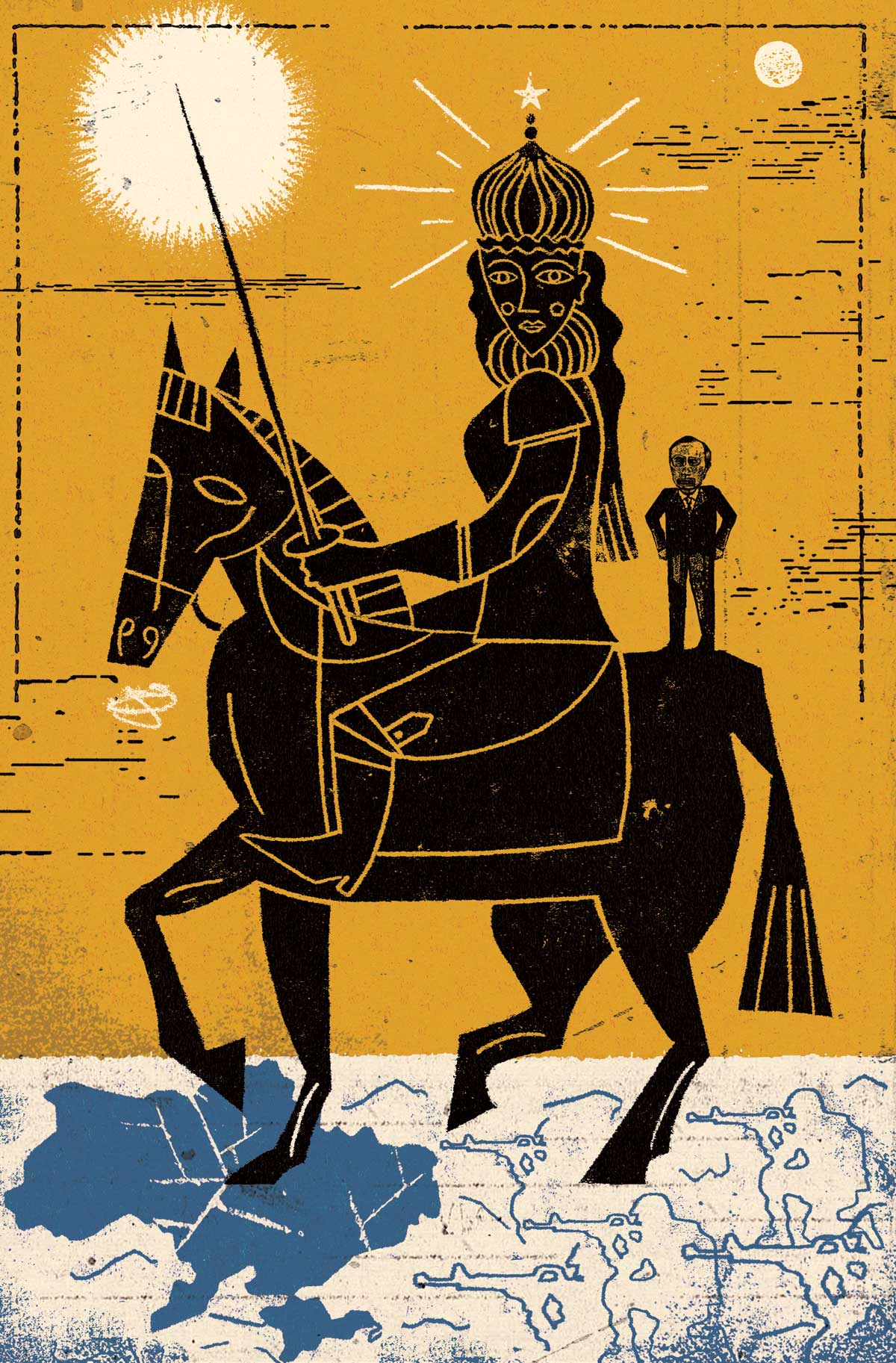

In January 1787 Catherine the Great travelled south from St Petersburg to survey some new imperial possessions. Crimea had been taken from the Ottoman Empire, the partitions of Poland were underway and the last vestiges of Cossack autonomy in the Ukrainian steppes had been eliminated. The journey was a grand event, lasting six months and covering 6,000 kilometres accompanied by thousands of soldiers and sailors.

The trip was elaborately stage-managed by Prince Grigory Potemkin, Catherine’s lover and the Governor General of the new territories. Catherine was treated to a private guard consisting of exotically attired Crimean Tatars; she encountered a parade of local Greek women dressed as Amazons (Herodotus had placed these mythical female warriors in the Black Sea steppes); Potemkin also surprised his empress with a spectacular firework display that spelled her name. All this effort gave rise to the myth of the ‘Potemkin village’: the prince, the story goes, ordered the construction of fake villages, nothing more than freshly painted façades, for the empress to view as she passed. These were dismantled and reconstructed further along the route, while herds of cattle were driven from place to place. Meanwhile, the peasantry lived in misery in the barren steppes.

The Potemkin village story is almost certainly a rumour spread by the prince’s enemies. Yet it nevertheless speaks to a deep Russian anxiety about its peripheries. Whether with the Finns, the Poles or the Chechens, Russia has always struggled with its subjugated peoples. Catherine, a self-styled Enlightenment ruler, saw it as her duty to understand those peoples – hence her journey. The knowledge she acquired, however, did not lead to mutual appreciation. She realised that the Ukrainian Cossacks in the steppes and the Tatars in Crimea were unreliable, so the Cossacks were dispersed and thousands of Crimean Tatars forced into exile. This, alongside deportations of Armenians and Greeks, led to catastrophic population decline in Crimea.

Novorossia

Potemkin had encouraged Catherine to annex Crimea precisely in order to emulate European powers that, he said, had ‘distributed among themselves Asia, Africa and America’. Like the Orientalist fantasies of the French or British Empires, Potemkin’s spectacles ignored cultural nuance and turned native peoples into exotic entertainments in order to hide the violence of colonisation. The image of Crimea as Russia’s own Orient would become a durable feature of Russian culture in the 19th century, as seen in popular literary works such as Pushkin’s lurid tale of love and vengeance in the harem, ‘The Fountain of Bakhchisaray’.

The conquest of Crimea was not only a foray into Asia: it also had a more ‘native’ significance. It was in 988 in the town of Chersonesus, then part of the Byzantine Empire, that the medieval ruler of Kyivan Rus, Volodymyr the Great, was baptised. From Kyiv, the faith spread north to the territories that later became Russia. Reconnecting with this Christian heritage helped join the dots between Russia’s rising imperial greatness and what it saw as its great Christian mission.

It is no wonder, then, that the current Russian state, with its neo-imperialist ambitions and Orthodox nationalism, is so fixated on the same territories that Catherine toured in 1787. In 2014, when Russia invaded Donbas and annexed Crimea, it even revived the name ‘Novorossia’, or New Russia, a term invented under Catherine for the newly annexed steppes. At the same time, Putin unveiled plans for a giant statue of his namesake Prince Volodymyr (Vladimir in Russian) in central Moscow.

In July 2021 Putin published a lengthy essay, ‘On the Historical Unity of the Russians and Ukrainians’, in which he aired multiple grievances against Ukrainians, while simultaneously denying their existence as a separate nation. He reached the contradictory conclusion that ‘genuine sovereignty for Ukraine is only possible in partnership with Russia’. Just as Catherine did in the 18th century, Putin proposes to bring order to what he views as an unruly borderland.

Ungrateful heirs

Ukrainians have long been aware of Russian imperial mythmaking. Nostalgia for the 17th and 18th centuries, when Ukraine’s Cossacks enjoyed significant autonomy and its peasants felt protected by them, developed soon after Russia’s expansion southwards. With Ukrainian historiography obstructed by tsarist censorship, the job of preserving the past fell to writers like Taras Shevchenko, Ukraine’s national poet. Born a serf in 1814, he felt the reality of Russia’s ‘enlightened’ rule, which had drastically worsened the conditions of the peasants in the decades before his birth. Shevchenko, despite his poverty, was able to gain a basic education and displayed a flair for drawing. His owner cultivated him as his personal artist and allowed him to enter the St Petersburg art world. Through the efforts of his well-connected friends, Shevchenko was able to buy his freedom.

While he trained as an artist, Shevchenko began to write poetry inspired by folk legends about Ukraine’s past. His narrators were ancient bards haunting the lonely grave mounds of the Cossacks who, in centuries past, had resisted colonisation from all sides: Russia, Poland, the Ottomans. He scolds Ukraine’s elites, the ungrateful heirs to the Cossacks, who are busy making careers in the imperial capital, while the peasants languish in chains. ‘History’, Shevchenko warns, ‘is the epos of a free nation’, which Ukrainians must read in order to understand ‘who we are … and by whom and why we are enslaved.’

Shevchenko’s world view was not narrowly nationalistic, however. One of his most famous poems, ‘The Caucasus’, satirises the imperial view of the Muslims of the north Caucuses, another object of Russian expansion, as barbarians in need of Christian instruction. The poem is a damning indictment of a state that purports to bring enlightenment, but in which ‘from the Fin to the Moldovan/each is silent in his own tongue’.

Secular martyr

The manuscripts of Shevchenko’s unpublished political poems fell into the hands of the secret police and he was arrested in 1847, sentenced to ten years of military service in exile and banned from writing or painting. This fate and his anti-imperial message turned him into a secular martyr in Ukraine, where his image and his words are still regularly encountered. One of the slogans of the Maidan protests in 2013-14, which opposed the government’s sudden decision to abandon an agreement with the EU in favour of closer links with Russia, was a line from ‘The Caucasus’: ‘Fight and you will prevail.’

Shevchenko’s calls to protect history from imperial distortion were not unique, but part of a broader cultural movement. Before Shevchenko, however, this was a cautious, apolitical project pursued by linguists, folklorists and historians. Many were members of the gentry who dabbled in literature, like Vasyl Hohol-Ianovskyi, who wrote quaint Ukrainian-language comedies for a provincial theatre in central Ukraine. Vasyl was an unremarkable writer, but his love of Ukrainian culture had a profound influence on his son, Mykola, known to the world as Nikolai Gogol.

Cossacks in Petersburg

While Gogol grew up participating in his father’s Ukrainian dramatic projects, as soon as he was old enough he moved to St Petersburg to forge a literary career in Russian – the only viable language for an ambitious writer at the time. When his first works were badly received, he did what writers are often advised to do and wrote about what he knew: Ukraine. He composed a letter to his mother asking for details of traditional Ukrainian culture and used these to produce two volumes of colourful, hilarious tales of Ukrainian village life. He also read widely in Ukrainian history (even applying to become a professor of Ukrainian history in Kyiv). His stories are full of subtle references to the golden age of the Cossacks.

Unlike Shevchenko, Gogol never openly expressed anti-imperial views. He was generally conservative in his outlook and the idea that his works might be seen as subversive caused him great anxiety. Yet his Ukrainian tales contain some deeply ambiguous dramatisations of the imperial encounter that took place in 1787. In his story ‘Christmas Eve’ a village blacksmith travels to St Petersburg in order to find a pair of boots fit for the empress as a gift for his fiancée. He accompanies a group of Cossacks to an audience with Catherine and Potemkin: the prince, the empress tells them, has promised to ‘familiarise her with her people’. She then proceeds to ask them a series of absurd questions about their habits and traditions, making clear she has not the foggiest notion of ‘her people’. The Cossacks reply politely, but quickly move on to their own priorities: expressing their dissatisfaction with the brutal dispersion of the Cossack army, which Catherine ordered and Potemkin had executed. Just as the grievances are aired, however, the blacksmith asks for the boots: his naive request charms the tsarina and the tension is diffused.

Fake empire

Gogol’s ability to subtly mock imperial ignorance of his homeland has not been lost on Ukrainians. One of the most joyfully subversive films made in Soviet Ukraine was The Lost Letter (1972), a loose adaptation of Gogol’s story of the same name, with a screenplay by the dissident Ivan Drach. Two Cossacks make the perilous journey from Ukraine to St Petersburg in order to deliver a message from the Hetman (Cossack leader) to the empress. When they finally gain an audience, Catherine laughs at their naivety in going to such lengths to deliver what turns out to be a trifling note. At this moment of miscommunication and mockery, one of the Cossacks slaps Potemkin, upon which the heroes realise that the rulers are not in fact real, but mere paintings on the palace wall. When they leave in disgust, slamming the door behind them, the entire building shakes like a stage set. The empire itself is a flimsy illusion, a Potemkin village.

This last scene did not go down well with the Moscow censor. Much as the USSR positioned itself as anti-imperialist, its view of Ukraine differed little from Catherine’s: The Lost Letter was banned in 1973 for its disrespectful portrayal of the Russian empress. Two years later, Vladimir Putin embarked on his career in the KGB.

Uilleam Blacker is Associate Professor in the Comparative Culture of Russia and Eastern Europe at UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies.

Source: History Today Feed