A Hidden Chapter: Women of the Klan - 11 minutes read

The Ku Klux Klan has entered popular memory as a sometimes menacing, sometimes almost comical, group of angry men, clad in white robes with hooded faces, setting crosses alight, or thundering through Reconstruction-era American towns on horseback. This image, however, fails to convey just how deeply women contributed to the work of the KKK.

The Klan went through three major phases – 1860-70, 1915-30 and 1950-70 – and women played a vital part in each of them. The first KKK took shape in Pulaski, Tennessee between 1865 and 1867, just after the civil war, during the period of Reconstruction. It was formed as a way of reasserting white supremacy over newly liberated black men and women. Women were not formally allowed to join, but they supported their husbands, sons and brothers, sewing uniforms and, according to the legal scholar Lisa Cardyn, providing ‘food, shelter, and emotional sustenance’ to Klan members.

Women also played a central role in the imagination and rhetoric of the Klan. The notion that white women were at risk from the unwanted sexual advances of black men was one of the group’s founding myths. An astonishing amount of information about the early Klan is available in the records of a Senate judiciary enquiry into it, held in 1871. The ‘Grandmaster’, Nathan Bedford Forrest, testified that ‘Ladies were ravished’ by ‘some of those negroes’ and that the Klan could deal with the problem better than the law. Upon initiation, the KKK required would-be members to take an oath, promising to protect ‘females, friends, widows, and their households’. At least one elderly woman adamantly asserted, many years later, that the Klan helped ‘to make it safer for white women’.

Ida B. Wells, the anti-lynching activist, pointed out, in a scorching 1895 pamphlet entitled The Red Record, that the Klan’s accusation of rape against black men was a ‘cowardly and infamously false excuse’. Decades later, Billie Holliday’s haunting anti-lynching ballad ‘Strange Fruit’ (written by the Jewish composer, Abel Meeropol) delivers the same sentiment with more irony: ‘Pastoral scene, of the Gallant South, the bulging eyes, and the twisted mouth.’ White women knew of their responsibility in this myth. Some pledged to combat the sanctification of Southern white female purity and fight lynching. Many did not, as the photographs of public lynchings, complete with women and families in the thousands, illustrate. Women packed picnics for these events and collected commemorative photographs of them for family scrapbooks.

Birth of a movement

The first Klan collapsed in the early 1870s. But women came into their own in its second incarnation. The old accusation was still part of Klan ideology. In 1917, a women’s group, the Daughters of the Confederacy, presented a plaque to the town of Pulaski, commemorating the Klan’s founding. One of their members, Grace Meredith Newbill, unveiled it, as a local pastor pronounced that the Klan had been an ‘army of defense and a safeguard of virtue’.

The second phase of the KKK was inspired, in part, by the film Birth of a Nation (1915), in which a white woman is attacked by a black man (a white actor in blackface). But this myth was accompanied by a massive outreach effort that expanded the KKK’s target audience – and the targets of their hatred. Klanswomen were surprisingly progressive and dauntingly efficient. Women helped weave the KKK into the mainstream of American society during the era and 500,000 joined their women’s auxiliary (the WKKK), while the KKK’s membership (which remained male-only) swelled to five million.

One of the women who was central to the Klan’s success was the publicist, lobbyist and businesswoman Elizabeth (Bessie) Tyler. The historian Linda Gordon describes her as ‘driven, bold, corrupt, and precociously entrepreneurial’. Tyler teamed up with a Klan member, Edward Young Clarke, to form the Southern Publicity Association. Together they offered their services to the then Grand Leader of the Klan. In the first six months of their employment, Klan membership grew by 85,000 – earning Tyler and Clarke hundreds of thousands of dollars on commission. A canny strategist, Tyler realised that the KKK needed local interest to expand its membership throughout America. She sent out agents to survey local communities and identify their concerns. As a result the revived Klan targeted not simply (nor even mainly) black Americans, but Catholics, Jews and any new immigrants to the country.

One of the most insidious aspects of Tyler’s service to the Klan was her adept use of newspapers. She gave interviews to the mainstream press and, whether they were trying to establish the danger of the KKK or merely offer their readers information, the interviews galvanised interest – and membership. The advertising emphasised the wholesome and socially protective role both women, and the Klan, could play in America. The Washington Chapter advertised these values in its recruitment poster:

To the American Women of Washington:

Are you interested in the welfare of our Nation? As an enfranchised woman are you interested in Better Government? Do you not wish for the protection of Pure Womanhood? Shall we uphold the sanctity of the American Home? Should we not interest ourselves in Better Education for our children? Do we not want American teachers in our American schools? IT IS POSSIBLE FOR ORGANIZED PATRIOTIC WOMEN TO AID IN STAMPING OUT THE CRIME AND VICE THAT ARE UNDERMINING THE MORALS OF OUR YOUTH. The duty of the American Mother is greater than ever.

Daisy Barr, the eventual leader of the Indiana WKKK, found this message compelling. She represented the new woman of the 1920s – and of the Klan. Many of them were in favour of women’s suffrage, were literate and were actively involved in political work and in their local church communities. Barr was an ordained Quaker minister and had advocated strongly for the inclusion of women in leadership positions in the church. Her husband was a bank examiner, the family was well off and she was a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which campaigned against alcohol and domestic abuse. She was prominent in the local Women’s Republican Party and was a passionate advocate for women’s education.

These women were typical of Klan women in the 1920s. Katherine M. Blee, the sociologist who first uncovered the extent of their power in 1920s’ America, identified their campaigns as both progressive on women’s rights and welfare, and utterly destructive, racist and xenophobic. She shows how they lobbied for education reform and conducted vicious campaigns to drive out Catholic schoolteachers and appoint White Protestant teachers in schools in their place. WKKK leaders also deployed ‘poison squads’ to slander politicians who did not support their anti-immigration goals; they fundraised energetically for those who did and voted for them. These women would march, often in the full regalia of their chapter, into schools to deliver Bibles to the class, or into churches to deliver large cheques to the pastor. They used a traditional women’s political tactic – the boycott – against businesses owned by Catholics, Jews and immigrants. They even devised the logo TWK – ‘Trade with Klansmen’.

From the same songbook

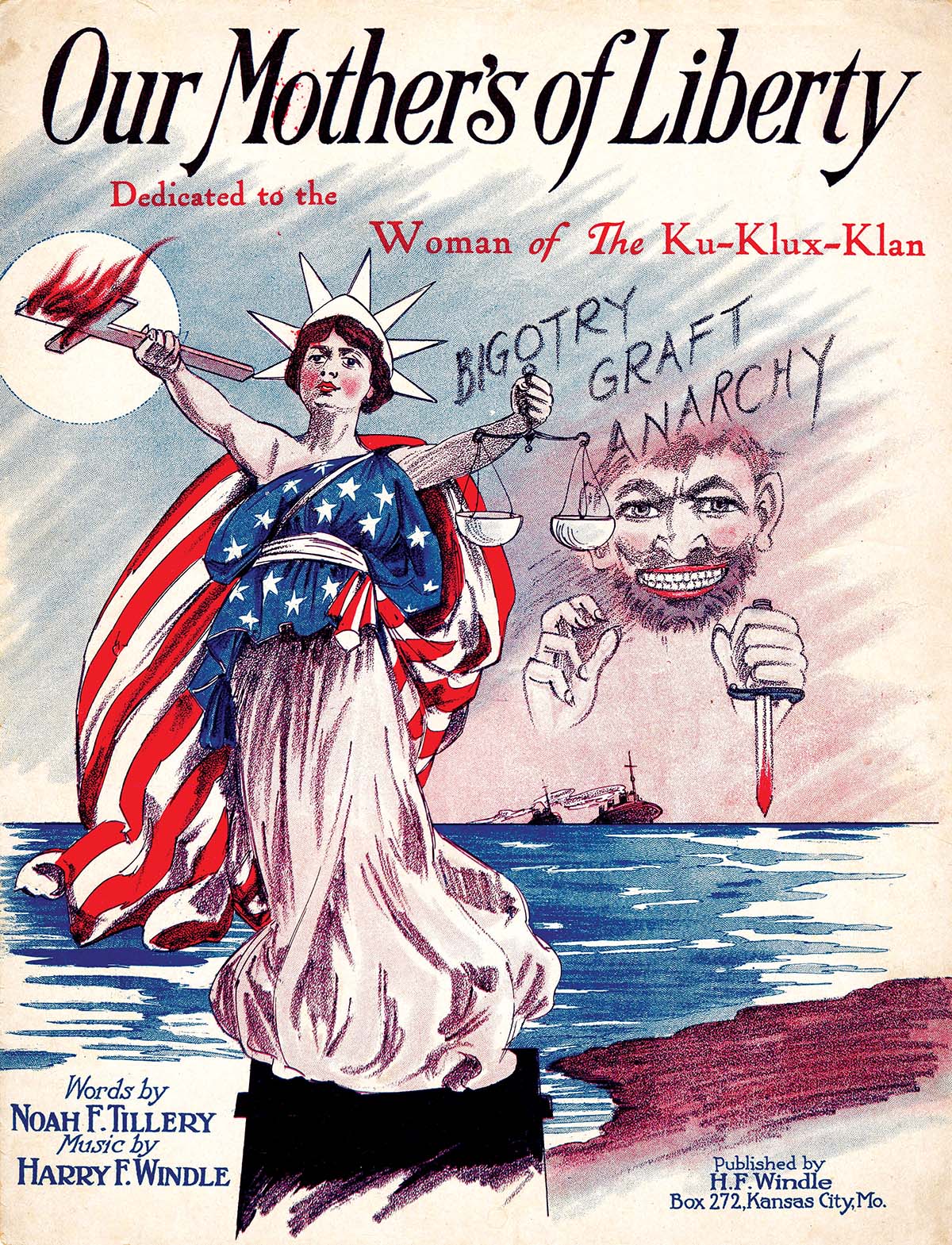

One of the artefacts of their work was the very public displays and concerts they organised. A day-long festival of sport and song would begin with a public parade and end with a twilight cross-burning and a series of uplifting addresses, lectures and speeches. Thousands of women and men participated. They sang songs from Musiklan, the official songbook of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan, featuring such works as ‘Onward Christian Klanswomen’ or ‘Yes, We Have Our Ku Kluxers’ (to the tune of ‘Yes, We Have No Bananas’).

These songs highlighted the connections between purity, motherhood, whiteness, American history and the central role of women in the Klan imagination. The chorus of ‘Our Mothers of Liberty’, for example, features the lyrics: ‘Women of the Ku Klux Klan, Pilgrims cherished dream / Things that brought them ’cross the sea – it’s your noble theme … Daughters of America, Protecting Liberty / Chastity of women and the White Supremacy.’

This second iteration of the Klan lost public credibility in 1927 after a wave of scandals. Bessie Tyler’s adulterous affair with her business partner was uncovered by police, who also charged the couple with the (then illegal) possession – and trading – of whiskey. Daisy Barr, leader of the powerful Indiana Women’s Klan, was accused of embezzling funds. Her nemesis, Mary Benudim, got into a public brawl over the leadership of the Indiana WKKK (although she went on to more political lobbying and became a considerable power in the 1950s).

Internal tensions

Yet, after the war and into the 1970s, the Klan got its third wind. This iteration, unlike the previous two, allowed women to join the formal organisation, rather than being relegated to a separate wing. Yet formal inclusion meant informal exclusion from leadership positions. Furthermore, as Katherine M. Blee notes, the impulses for opening membership of the KKK to women remained strategic and somewhat cynical. The leadership wanted voting members, particularly as the Civil Rights campaign promised to expand the black voting base. As they had during Reconstruction, the Klan sought to limit the impact of this political development. It was not the first time white women had chosen racial solidarity over the expansion of black suffrage: the early women’s suffrage campaign in America nearly foundered on this very tension. In the 1950s, however, the Klan continued to recruit women. And, when he appeared in the early 1970s, David Duke, Grand Wizard (1974-80), advocated for women’s involvement to build the Klan’s base of registered voters.

In her more recent work on extremist racist groups in the 1990s, Blee identifies several other motives that led to women’s incorporation into the Klan and other right-wing organisations. Women bring men in and serve as recruitment agents. Leaders believe that they cement the social ties in local chapters and they serve in an organisational capacity, which brings stability to the membership.

In the 1970s the FBI cracked down on overt Klan membership, violence and cross-burnings. As a result, women became even more attractive recruits than in the 1950s, as they were less likely to have criminal records than the men; the police and the FBI had less leverage over them; and women could keep men from committing (non-KKK-sanctioned) crimes, thereby becoming vulnerable to imprisonment. Blee noted, in an interview:

Today’s racist groups have a lot of women in them, more than half in some, but the women are there in a provisional way; they’re only supposed to be there to talk to the men and make sure they don’t commit crimes. A lot of these groups have conflicts between men and women and none have women leaders. One group in the Klan was going to have a woman leader – the daughter of a Klan leader who was going to retire – but there was so much hubbub and anger from other men, that he ended up not retiring, because he couldn’t turn it over to her.

Despite this conservative and traditional gender role, Blee notes that a number of the right-wing women she interviewed in her work on contemporary right-wing extremist groups were wage-earning, literate professionals. They were organised, competent and effective. They raised money and set up information networks.

Remember the ladies

Women have always been recognised as agents who can inculcate values in the home. Mary Wollstonecraft deployed the argument that women should be educated because, as mothers, they had a responsibility for the education of future citizenry. That call was quick to reach America, where Abigail Adams and other early feminists reminded the Founding Fathers to ‘remember the ladies’ and make provisions for them in the new nation. Of course, while strategically employing this maternal, domestic argument, both women were prolific writers and thinkers and active in the politics of their time. Women have followed their example in ways that have shaped America in both progressive and racially oppressive ways.

The history of women in the Klan is one of large numbers of highly competent and progressive women, who have shored up racism and countered immigration. Heeding Abigail Adams’ words, we should ‘remember the ladies’ in all their complexity.

Rachel Gillett is Assistant Professor in Cultural History at Utrecht University.