Regulation and Reputation | History Today - 3 minutes read

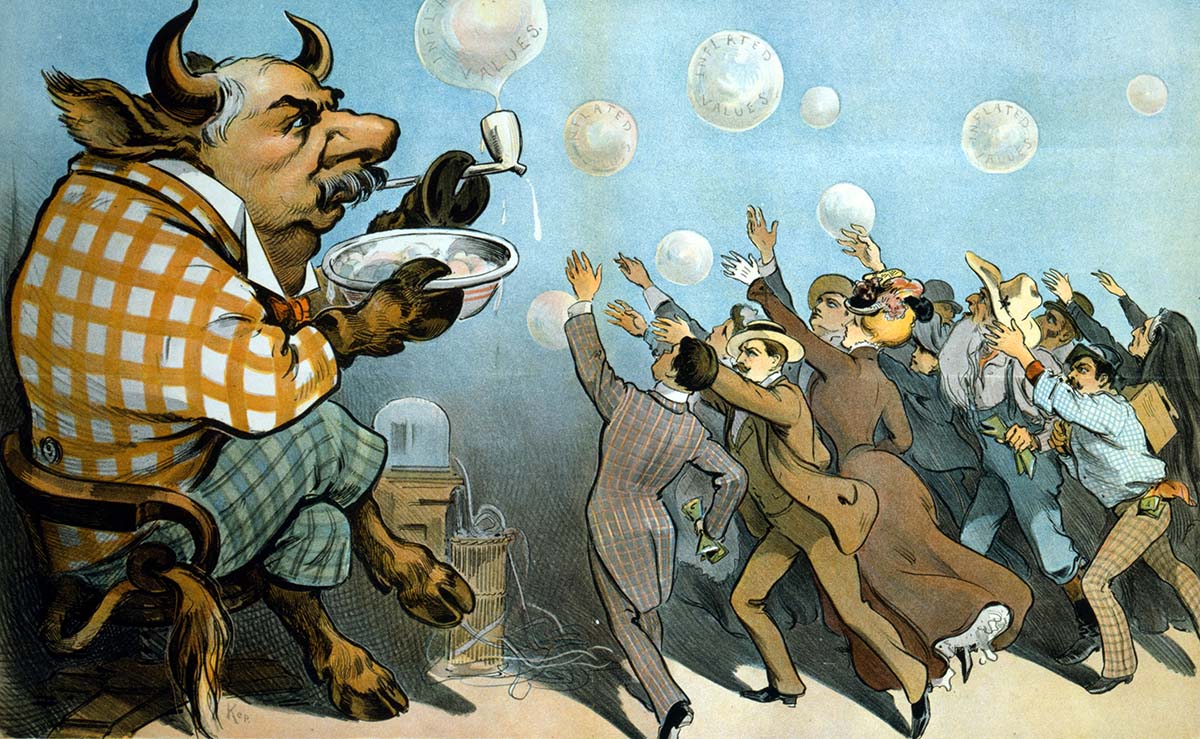

Booms, with hindsight, may prove bubbles. So it is that Alan Greenspan, appointed Federal Reserve chairman by Ronald Reagan and hailed by the Washington Post’s Bob Woodward as the ‘maestro’ of Wall Street’s extraordinary 1990s gains, has suffered a plummet in reputation since the 2008 financial crisis. As Bloomberg’s John Authers wrote recently, Greenspan is ‘widely viewed as one of the chief culprits of the financial crisis, cutting rates whenever stock markets seemed to run into trouble’, thereby inflating ‘an epochal credit bubble’.

Born in 1926 and initiated in the 1950s into Ayn Rand’s circle, Greenspan, at 92, has been a witness to most of the history recounted in Capitalism in America, two thirds of which concerns the 1920s to the present. The smart money would suggest that his co-author, Adrian Wooldridge of the Economist, bears most responsibility for the book’s actual composition, but it cannot have escaped the publishers that Greenspan’s celebrity would improve talk-show prospects and stimulate sales among business travellers making impulse buys on layover.

The partnership yields a paean to American capitalism. It draws on Joseph Schumpeter’s classic notion of ‘creative destruction’, a pitiless commitment to productivity-enhancing processes and technologies. Capitalism in its American version has been exceptionally efficient and ‘democratic’. Critics of injustice, ‘workers who try to defend their obsolescent jobs’ and academics sceptical of ‘shareholder capitalism’ are blind to the wonders of a system that delivers bounty for all.

Most of the book is a textbook economic history dotted with familiar stories, such as those of Alexander Hamilton, John D. Rockefeller and Bill Gates, cast heroically. The index contains neither ‘exploitation’ nor ‘speculation’, let alone Bernie Madoff. Capitalism is never defined. A focus on business, finance and technology plays to the authors’ strengths (though their nostalgia for the gold standard may raise an eyebrow), but it shows no awareness of recent scholarly understandings that explain capitalism not merely as ‘the economy’ but a whole social order, with a distinctive class structure, systemic dynamics including intrinsic propensity for crisis and a corollary culture and civilisation.

The authors separate out the ‘the capitalist economy of the North and the slave-owning economy of the South’, though the two were profoundly connected. Slavery’s great expansion came with capitalism’s take off, as historians dating back to Eric Williams emphasise. Cotton and tobacco were eagerly sought: the wealth of 19th-century Manchester and London owed much to Alabama and Mississippi. Slaves themselves were commodities to be bought and sold and plantation owners sought maximum returns on investment. The ensuing connection under segregation between race and capitalism is similarly elided.

This tale of boundless progress ends fitfully. Deregulation under Reagan and Clinton is praised, then inadequate regulation is admitted as a serious factor in the financial crisis. Finally over-regulation is said to plague the US today. No thought is entertained that unprecedented concentrations of wealth and income may help account for economic instability. Positing a coming inflation for which no evidence is provided, the book proposes to revive capitalism by cutting ‘entitlements’, namely Medicare and Social Security, a grim medicine whose only certain effect would be to increase inequality.

Capitalism in America: A History

Alan Greenspan and Adrian Wooldridge

Allen Lane

496pp £25

Christopher Phelps is Associate Professor of American History, University of Nottingham.