Forging Ties | History Today - 5 minutes read

Almost 80 years after the end of the Second World War, China and Japan continue to battle over how to remember it, each emphasising their own victimhood, ensuring that this division is passed onto the next generation. As Japan is China’s quintessential enemy in dominant narratives of the war, the story of Uchiyama Bookstore, a Japanese-owned bookshop in wartime Shanghai frequented by both Chinese and Japanese literati, stands out as an anomaly. Uchiyama Bookstore is not merely a feel-good story during a period characterised by antagonism and war, however.

Uchiyama Bookstore was run by a Japanese Christian couple, Uchiyama Kanzō and Miki, in Shanghai between 1917 and 1945. It was founded by Uchiyama Miki, who originally sold books related to Christianity, while her husband Kanzō sold eyedrops for a Japanese pharmaceutical company. Despite heightened tensions between Japan and China in the 1920s and 1930s, Uchiyama Bookstore flourished and began to serve both Japanese and Chinese customers. A Japanese governmental report assessing Japanese-language books and learning in China found that by 1937, while other Japanese bookshops in Shanghai primarily served Japanese customers, Uchiyama Bookstore’s patrons were 70 per cent Chinese and 30 per cent Japanese.

This was in part due to Uchiyama’s Japanese Christian customers, who were avid readers and asked that they expand their stock to carry new publications on a wider range of topics. The attraction of Uchiyama Bookstore to Chinese customers was that it carried the latest Japanese publications on medicine, politics, economics and law as well as left-wing books and magazines that were restricted in 1930s China, such as the works of Marx and Engels. Being in the international concession, Uchiyama Bookstore was immune from persecution under Chinese law. These books were highly sought after, particularly by Chinese students returned from their studies in Japan, who read Japanese translations of Western works.

As well as selling books, Uchiyama Bookstore served as a Sino-Japanese cultural salon frequented by Chinese and Japanese literati. After Kanzō left the pharmaceutical company in 1930, he took ownership of the bookshop, acting as a mediator for Sino-Japanese cultural exchanges with Miki’s assistance. The bookshop’s second floor had a dedicated social space, equipped with a table and chairs where customers could linger, drink tea and talk. A group consisting of Chinese students, Japanese residents of Shanghai and visiting Japanese writers gathered regularly at the bookshop and created a literary magazine, Kaleidoscope.

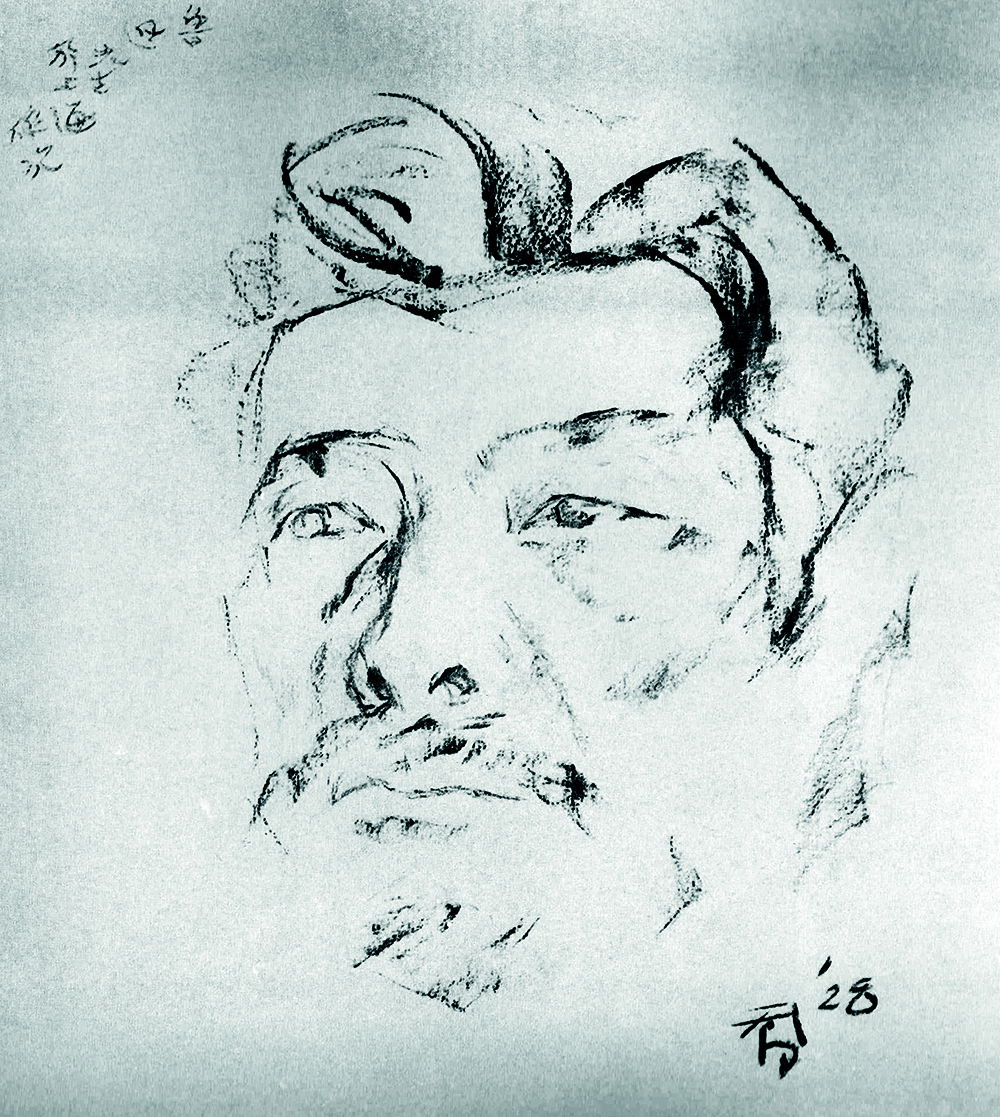

For writers who saw literature as a tool for reforming Chinese society, such as Lu Xun, the father of modern Chinese literature, and his contemporary Yu Dafu, a visit to Uchiyama Bookstore on North Sichuan Road became part of their daily lives. Another regular, Kaneko Mitsuharu, described their routine: ‘If I were to use Balzac’s expression, like two chestnuts in half, Lu Xun and Yu Dafu were always walking around on North Sichuan Road.’ Both Lu Xun and Yu Dafu recorded, almost on a daily basis, each book that they purchased from Uchiyama Bookstore, and Lu Xun would add details on gifts that he exchanged with Uchiyama, such as seaweed, toys for his son, or clothes. On multiple occasions, Uchiyama Kanzō made arrangements for Chinese writers such as Lu Xun and Guo Moruo to take refuge at the bookshop while they were being pursued by the Guomindang.

Uchiyama Bookstore played a pivotal role in jump-starting the modern woodblock print movement in China. Kanzō hosted a woodblock print workshop, with his brother Kakichi as the teacher and Lu Xun as interpreter, to teach young Chinese artists and organised woodblock print exhibits to showcase their work. Lu Xun saw in woodblock prints the evocative power to awaken the Chinese populace in a way that literature could not when a large portion of China’s population was illiterate. Woodblock prints would later be used by the communists to mobilise peasants during China’s war against Japan and the civil war with the nationalists.

As Japan and China went to war in the late 1930s, in person Sino-Japanese cultural exchanges at the bookshop were no longer viable, so Uchiyama shifted to publishing books and giving talks on China to Japanese audiences. Although the Shanghai Uchiyama Bookstore closed down with the end of the war and Uchiyama returned to Japan, his unceasing devotion to bettering Sino-Japanese relations continued. Following his return, he spent 17 months giving 800 talks throughout Japan during 1947. Uchiyama founded the Sino-Japanese Friendship Association, which was part of the larger postwar peace movement in Japan and which played a major role in returning the remains of forced Chinese labourers who died in Japan, as well as in repatriating Japanese orphans who were left behind in China. He also promoted normalising diplomatic relations with China, which was no easy task when Japan was under the US occupation of 1945-52 and was seen as a bulwark against communism during the Cold War. Uchiyama worked on forging further ties with his Chinese counterparts, building upon the networks that he had established during his 30 years in Shanghai.

The legacy of Shanghai’s Uchiyama Bookstore lives on in both China and Japan. In Tokyo, there is a bookshop district called Jinbōchō that began in the Meiji period (1868-1912) serving the numerous universities that sprang up, in which over 150 used and specialised independent shops operate to this day. Uchiyama Kanzō’s brother Kakichi opened the Tokyo Uchiyama Bookstore in Jinbōchō in 1935. Specialising in books on China, it is now run by Kakichi’s grandson.

Uchiyama Kanzō and Miki are buried in Wanguo Cemetery in Shanghai alongside other foreign friends of the Communist Party of China. Kanzō is remembered fondly in China due to his friendship with Lu Xun. In 2021, a new Uchiyama Bookstore opened in Tianjin, followed by the 1927 Lu Xun and Uchiyama Memorial Bookstore, which opened in 2022 on the site of the original Shanghai bookshop.

Naoko Kato is the author of Kaleidoscope: The Uchiyama Bookstore and its Sino-Japanese Visionaries (Earnshaw Books, 2022).

Source: History Today Feed