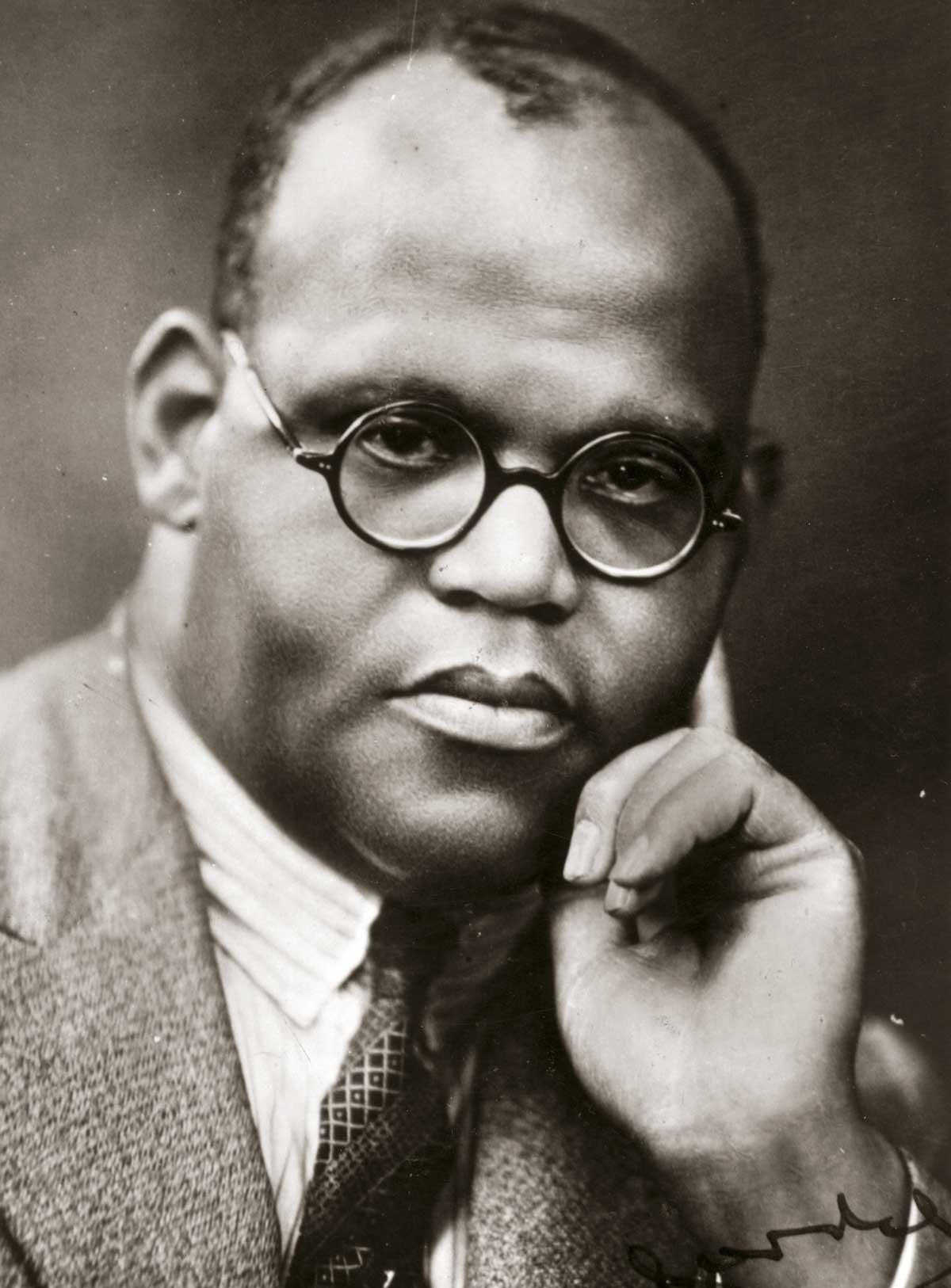

Harold Moody’s Fight for Racial Equality - 5 minutes read

Despite his pioneering role in the struggle for racial equality and justice in Britain, Harold Moody remains relatively unknown. It is now 70 years since the publication of the last substantial biography of his life and career. Yet Moody’s story is significant, not least as a reminder that the history of Black people and anti-racist activism in Britain long predates the Windrush generation.

When 492 West Indian migrants disembarked from the Empire Windrush at Tilbury docks in June 1948, Moody had already been dead for more than a year. By that time, he had actively promoted the cause of racial equality for the best part of two decades. Moody also demonstrates how Black Britons saw their campaign for the full rights of citizenship as one front in a broader global struggle for racial equality. Although Moody drew much inspiration from the Civil Rights movement in the US, his activism was not entirely imitative. On the contrary, his international vision led him to promote reform throughout the British Empire and beyond.

Harold Moody was born in Kingston, Jamaica on 8 October 1882. He came to Britain in 1904 to study medicine at King’s College London. Despite graduating at the top of his class, he found it impossible because of the colour of his skin to secure a position in the medical profession and had to establish a practice in Peckham, south London. This experience of discrimination, coupled with a devout Christian faith, impelled Moody’s activism.

In 1931, assisted by the African-American activist Charles Wesley, Moody took inspiration from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and established the League of Coloured Peoples. Although its membership never exceeded 500, the League became an influential advocate for equality.

Moody’s sense of common purpose with other campaigns against racism around the world led the League to promote educational and employment opportunities in British colonies throughout Africa and the Caribbean as a means of advancing their eventual independence. It furthermore petitioned the US Embassy in London against the lynching of African Americans and for the release of the Scottsboro boys, nine Black teenagers wrongly convicted of the rape of two white women in Alabama in 1931, as well as successfully lobbying on behalf of Black seamen against employment restrictions by Cardiff port authorities.

The League made its most important contribution to the cause of racial equality during the Second World War, however, when it helped to persuade the government in October 1939 that British citizens ‘not of pure European descent’ could volunteer for the armed forces and secure commissions.

Discrimination in the military and on the Home Front had led the Pittsburgh Courier, an African-American newspaper, to demand that the US war effort focus on freedom at home as well as overseas. Moody emulated this in declaring that, for the British government to uphold the democratic ideals for which the Allies were fighting abroad, it also had to address the problem of domestic racism. ‘It is high time’, he asserted, ‘that we realised we cannot be fighting a war against Nazism and at the same time be perpetuating its principles within our own borders.’

An even greater convergence of British and US activism came with the arrival of American GIs to the UK from May 1942. Moody protested against the impact that the racism of many of these soldiers had on West Indian servicemen in Britain, including insults, assaults and exclusion from dance halls.

The League further responded to social challenges stemming from the presence of the GIs in Britain, commissioning, in 1945, a report for the League of Coloured Peoples on the 2,000 children born to African-American servicemen and white British women. The report’s author, Sylvia McNeill, recommended that the government should treat these children (known as ‘brown babies’) as a ‘war casualty’ and provide appropriate support. Moody lobbied for state intervention, observing that ‘when what public opinion regards as the “taint” of illegitimacy is added to the disadvantage of race, the chances of these children having a fair opportunity for development and service are much reduced’. Far from seeing them as wards of the state, though, the government had many of the children put into private care homes.

The most ambitious expression of Moody’s internationalism came with the Charter for Coloured Peoples. Ratified in July 1944, the document was inspired by the Atlantic Charter, a statement signed by Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt in August 1941 that outlined Allied aims for the Second World War, including ‘The right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live.’ Churchill insisted that the Charter applied only to European countries under Nazi occupation. ‘I have not become the King’s First Minister’, he declared in the Commons, ‘in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire.’

The Charter for Coloured Peoples challenged Churchill. It called for equality of all, regardless of race, and pushed Allied countries to restore self-rule to nations under their colonial rule. In aligning with nationalist movements in Burma, India, Nigeria and elsewhere, the League helped blow what Prime Minister Harold Macmillan would later call ‘the wind of change’ that swept through the old colonial empires.

Criticised for his political moderation by more radical contemporaries, such as George Padmore and C.L.R. James, Moody was nonetheless a pioneering reformer who worked within the political system as an effective advocate for Black Britons. At the time of his death on 24 April 1947, he was attempting to raise funds for a new cultural centre that foreshadowed the later emphasis on Black culture in the late 1960s. In continuing to push for an end to discrimination, not only in Britain but throughout the world, Moody also articulated an international vision that anticipated the universal message that Black lives matter.

Clive Webb is Professor of Modern American History at the University of Sussex.

Source: History Today Feed