The Young Crusaders | History Today - 6 minutes read

The doors of the Queen’s Hall, London, opened at 7.15pm on 16 April 1930. The evening featured a performance from Ambrose’s band – the largest jazz band in the country, with 33 musicians – as well as ‘up to the minute’ community singing conducted by Gibson Young. The audience of 3,000 under-25s, ‘most of them well known in London society’, danced along to both. A reporter from the Daily Express reported the following day: ‘One has a sentimental attachment for the old songs and the old tunes, but, for all their lilt, and their melody, they do not move to the pace which this postwar life demands.’

This might sound like a trendy social gathering, but it was actually the launch of the Young Crusaders, an initiative attached to Lord Beaverbrook’s Empire Crusade. That the Express gave it such glowing coverage, with similar front-page articles in the run up to, and in the days following, the event, was only to be expected. The Express, alongside the Sunday Express and the Evening Standard, were owned by Beaverbrook and he used his newspapers as political weapons.

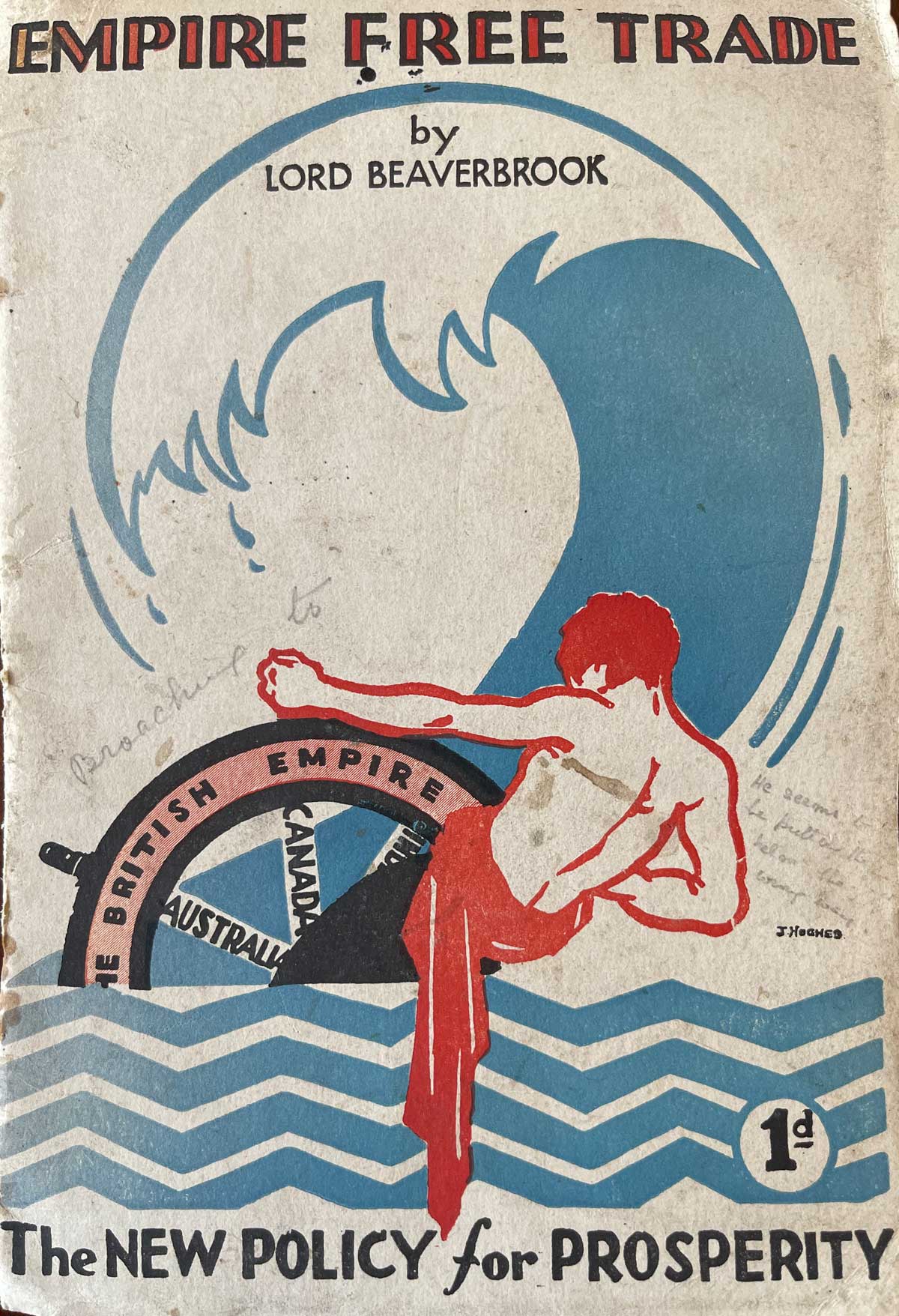

Beaverbrook launched the Empire Crusade in July 1929, aiming to pressure the Conservative Party and its leader Stanley Baldwin into implementing a strong form of imperial preference (reducing tariffs between Empire nations). Having tasted defeat running on such platforms in earlier general elections, many leading Conservatives were wary of pushing the policy too strongly again. Baldwin thus pursued a much more limited programme of national protection. Beaverbrook called for not just imperial preference, but for Empire Free Trade – a large tariff wall around the Empire with full free trade within. This, he believed, would tie the Empire inextricably together.

The Crusade’s most enduring legacy relates to a speech Baldwin gave before what was deemed a pivotal by-election at Westminster St George in March 1931. With the Crusade in full swing, Baldwin had faced intense pressure from his backbenchers and local Conservative Associations. He saw an opportunity to turn the tables, however, framing the by-election as being fought over the threat posed by irresponsible newspaper proprietors, stating: ‘What the proprietorship of these papers is aiming at is power, and power without responsibility – the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages.’ His candidate duly defeated the Crusade’s candidate.

Yet, as the Young Crusaders show, there was more to the Crusade than just by-election campaigns.

The fact that Beaverbrook chose to launch a youth movement was unsurprising given his fixation on the young; he often called for young men to be bold enough to tackle the issues that the ‘old men’ of politics were, he claimed, unwilling or unable to handle.

More broadly, the early 20th century was a boom period for youth organisations. The largest youth movement of the time, the Scout and Guide associations originally founded in the Edwardian period with an imperial focus, had by 1930 around a million members. Similar initiatives such as the Boys’ Brigade followed, while other youth groups, such as the Woodcraft Folk, provided less jingoistic alternatives for those wishing to pursue outdoor activities. Developments on the Continent also provided inspiration, with Beaverbrook requesting information from the Express’ Berlin correspondent, Sefton Delmer, about a German youth movement called the Wandervogel (‘Wander Birds’). From 1930 to at least 1932, the Young Crusaders were given permission to camp on the grounds of Beaverbrook’s manor house in Surrey.

Political organisations similarly rushed to make inroads among the youth. The Liberals, the Labour Party, the Independent Labour Party and the Communist Party of Great Britain all launched youth branches and there were the socialist Sunday schools. The Conservatives developed youth wings of their own: the Junior Imperial League was founded in 1906, followed by the Young Britons League in 1925. One recurring issue with these groups was a tension between their social benefits and their efforts at politicisation. Complaints often arose that many attendees wanted to listen to music and have a chance to meet the opposite sex, rather than to seriously engage with political ideology.

This was no doubt true of the Young Crusaders and news reports of its initial meeting emphasised the social and musical benefits it offered. Nevertheless, Empire Free Trade and reverence for the Empire were centre stage. The hall was festooned with imperial flags and a vast map of the Empire was suspended over the stage. Beaverbrook spoke for 40 minutes at the inaugural meeting (with the Express stating, naturally, that the young audience was rapt, sat in ‘dead silence, punctuated by wild outbreaks of cheering’). A number of young people stood to eulogise the Empire and its historical heroes, themes continued in mass chants. Local branches of Young Crusaders were created in Oxford, Southwark and Westminster – among other places – and received prominent coverage in the Express.

The St George’s by-election is usually thought to signal the Crusade’s end, one steeped in failure. As the ongoing activities of the Young Crusaders makes clear, however, the Crusade endured for a while longer. Indeed, its fund continued to financially support candidates into the late 1930s and Beaverbrook’s newspapers continued to campaign for Empire Free Trade even after the Second World War.

The Crusade arguably had more impact than is generally recognised. After all, Britain did implement imperial preference at the Ottawa Conference in 1932. Other factors undoubtedly played a role in this outcome, such as protectionist support within the Conservative Party, fractures among advocates of free trade and the activities of protectionist pressure and industry groups, such as the Empire Industries Association. Beaverbrook’s propaganda efforts should not be overlooked, however. The sustained campaign for imperial preference in his newspapers throughout the interwar period, which was ramped up from 1929 to 1932, undoubtedly had a greater impact than the Young Crusaders. But, with their mix of jazz and imperialist chants, political speeches and camping, the Young Crusaders provide a fascinating insight into the social and political world of interwar Britain.

Aaron Ackerley is a Teaching Associate at Queen Mary University of London.

Source: History Today Feed