Books of the Year 2022 - 9 minutes read

‘Tracing colonial officials who left utterly dislocated societies in their wake’

R.J.B. Bosworth, Author of Politics, Murder and Love in an Italian Family: The Amendolas in the Age of Totalitarianisms (Cambridge University Press, 2022)

When I was a young lecturer in Sydney and began teaching a course on ‘European fascism’, an older, wiser colleague told me that the reason Oswald Mosley got nowhere with the British Union of Fascists was because all the potential fascist bosses in the United Kingdom were out in the Empire. Caroline Elkins’ Legacy of Violence: a History of the British Empire (Bodley Head) suggests that he may have been right, as she traces a Namierian pattern of colonial officials who moved from one site to the next and left corpses, population transfers and utterly dislocated societies in their wake.

Also important as Giorgia Meloni takes the neo-fascist Fratelli d’Italia party into government in Rome is Paul Corner’s devastating Mussolini in Myth and Memory: The First Totalitarian Dictator (Oxford University Press), showing why Italian memory is fecklessly ready to tolerate a contemporary politician who thinks that the Duce was a great statesman.

‘Narrative history at its finest’

Ian Garner, Author of Stalingrad Lives: Stories of Combat and Survival (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022)

Peeling back the layers of myth surrounding the Battle of Stalingrad is a tall order. In The Lighthouse of Stalingrad: The Hidden Truth at the Centre of WWII’s Greatest Battle (Constable) Iain MacGregor brilliantly dissects the story of Pavlov’s House, the building supposedly defended by a small group of Soviet men against overwhelming odds.

Serhii Plokhy’s Atoms and Ashes: From Bikini Atoll to Fukushima (Allen Lane) examines six nuclear disasters, revealing the connections between national security, safety and civilian suffering. The book contains lessons for a world returning to nuclear power as governments prepare to fight climate change.

Andrew Stobo Sniderman’s Valley of the Birdtail: An Indian Reserve, a White Town, and the Road to Reconciliation (HarperCollins) charts the life of two communities – one a town of Ukrainian refugees, the other inhabited by Indigenous peoples – as a means of exploring Canada’s history over the last 150 years. It is narrative history at its finest.

‘What we choose not to know can change global events’

Gina Anne Tam, Assistant Professor in History at Trinity University, Texas and the author of Dialect and Nationalism in China, 1860-1960 (Cambridge University Press, 2020)

Gao Yunxiang’s Arise, Africa! Roar, China! (University of North Carolina Press) highlights five remarkable stories of transnational activists who forged solidarity movements among Black American Leftists and Maoist Chinese in the 20th century. The story of Silvia Si-Lan Chen Leyda, a Sino-Caribbean dancer and choreographer, is particularly memorable.

Henrietta Harrison’s The Perils of Interpreting: The Extraordinary Lives of Two Translators between Qing China and the British Empire (Princeton University Press) takes a familiar story – the deteriorating diplomacy between Britain and Qing China from the 1793 Macartney Mission and the Opium War – and masterfully retells it through the lives of two translators. Harrison’s intertwined biographies show how information is created and translated, but also how that information is subsequently lost, forgotten and ignored. What we choose not to know can change global events.

‘My favourite books explore the past but also ask questions about the future’

Patricia Fara, Emeritus Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge and winner of the 2022 Abraham Pais Prize for the History of Physics

My favourite books explore the past but also ask questions about the future: as the astrophysicist David Spergel remarked, ‘our history as humans has shown that first we screw things up, and then we make some things right’. In Science of Life and Death in Frankenstein (Bodleian Library) Sharon Ruston explains topics such as vitalism, resuscitation attempts and electrical medicine.

David Rooney’s wonderfully ambitious About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks (Viking) describes repeated bids to exert power through timekeeping – from Roman complaints about the tyranny of sundials to the environmental necessity of contemplating the Long Now.

In The End of Astronauts: Why Robots are the Future of Exploration (Bellknap Press) Donald Goldsmith and Martin Rees review the history of space travel to insist that humans are not fit for purpose: our galactic future depends on global collaboration in AI.

‘Intellectual engagement is not incompatible with ruthless megalomania’

George Garnett, Author of The Norman Conquest in English History: Volume I: A Broken Chain? (Oxford University Press, 2020)

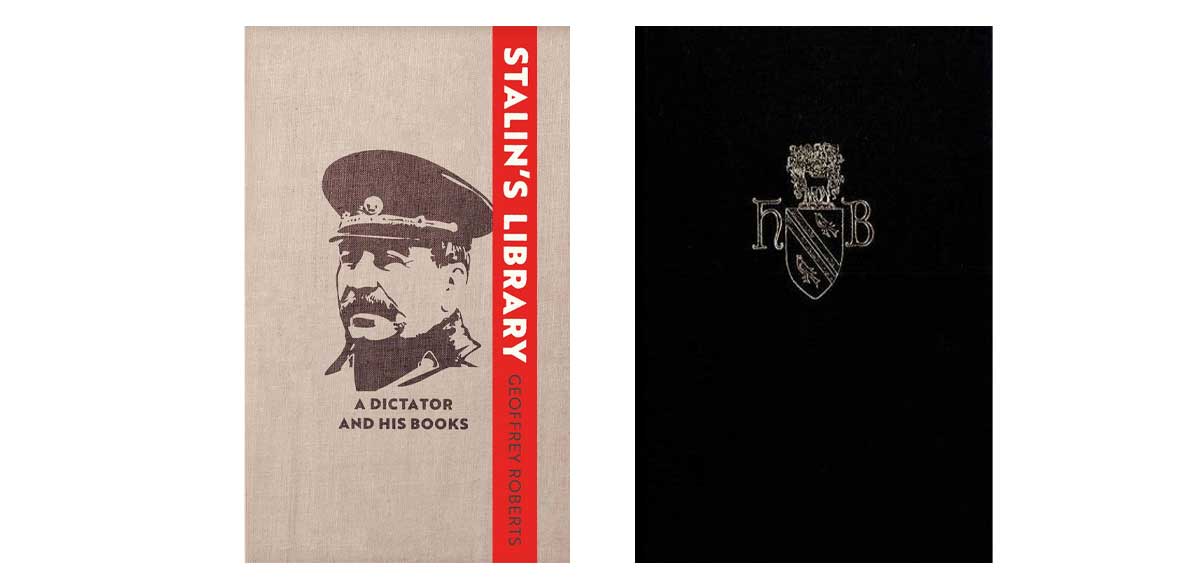

Geoffrey Roberts’ Stalin’s Library (Yale University Press) analyses the extensive marginalia Stalin left in hundreds of books. They reveal that intellectual engagement is not incompatible with ruthless megalomania. This will come as no surprise to those working in contemporary universities.

Edward Coke is the Shakespeare of English law. His Reports have been foundational for legal doctrine, as shown by the 2019 Supreme Court case on the prorogation of Parliament. John Baker has discovered the almost illegible notebooks on which the authoritative printed texts were loosely based. His Reports from the Notebooks of Edward Coke (Selden Society) transforms understanding of the genesis of English law under Elizabeth I and James I.

The forthcoming coronation will follow a template devised at the beginning of the tenth century. David Pratt’s Two English Coronation Ordines (Henry Bradshaw Society) could not be more timely.

‘What is it to practise history in a photographic age?’

Christina Riggs, Professor of the History of Visual Culture, Durham University and author of Treasured: How Tutankhamun Shaped a Century (Atlantic, paperback 2022)

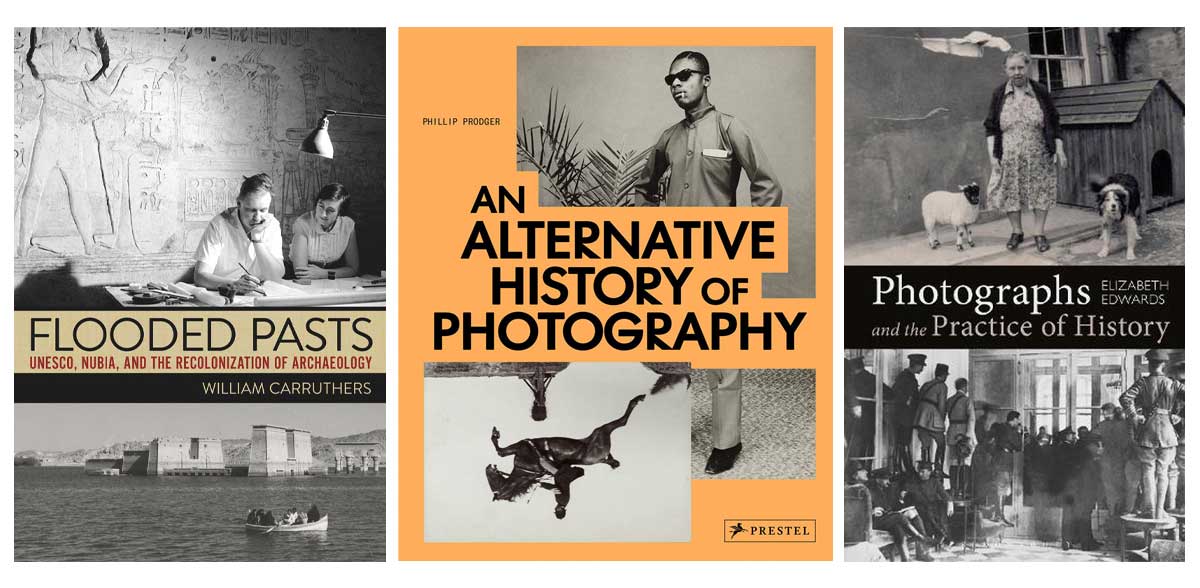

I can’t wait to see William Carruthers’ study Flooded Pasts: UNESCO, Nubia, and the Recolonization of Archaeology (Cornell University Press). In the 1960s and 70s, UNESCO’s Nubian salvage campaign propelled Tutankhamun back into the limelight, as Egypt sent his ‘treasures’ on tour, but heritage tourism and a consumer-driven concept of ‘Ancient Egypt’ have made the colonial origins of archaeology even more difficult to overcome.

Historians rarely consider how photography shapes the discipline itself. Elizabeth Edwards’ Photographs and the Practice of History (Bloomsbury) asks a crucial question: what is it to practise history in a photographic age? I’m also glad to see a new book challenge Eurocentric takes on the medium: Phillip Prodger’s An Alternative History of Photography (Prestel) probes its complexities with contributions by international scholars.

‘History unites and shapes the identities of citizens of the three major South Asian nation-states’

Radha Kapuria, Assistant Professor in South Asian History at the University of Durham

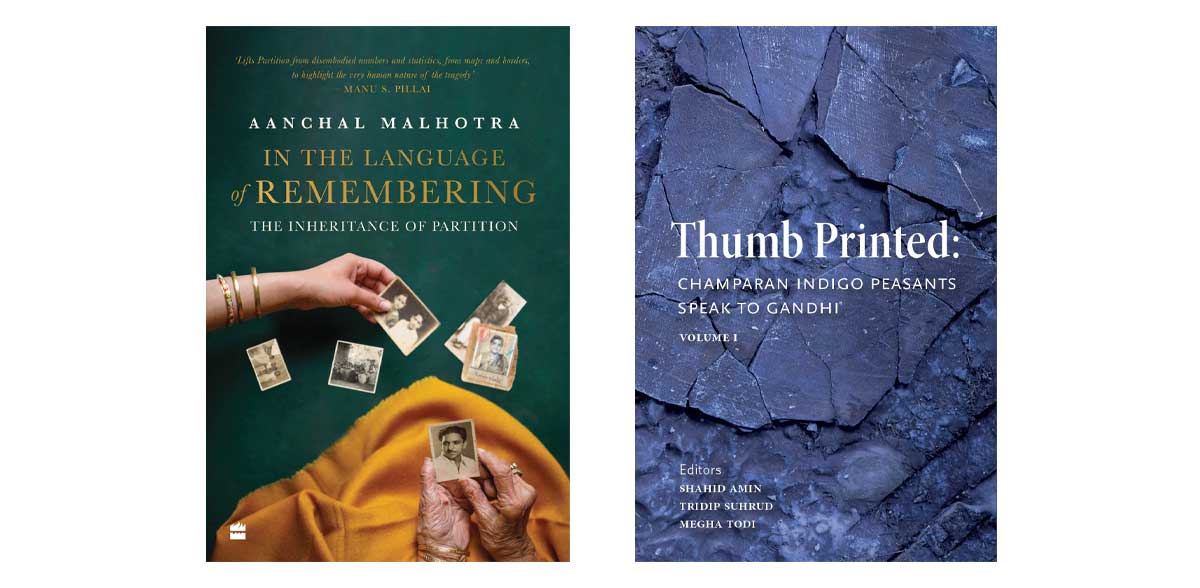

Published to coincide with Partition’s 75th anniversary, Aanchal Malhotra’s In the Language of Remembering: The Inheritance of Partition (HarperCollins) examines the impact of that cataclysmic event on the second and third generations of those families who experienced the traumas of 1947. Concerned with nostalgia, trauma and memory, it is a sequel to her Remnants of Partition (2017). Building on interviews with Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis in South Asia and across the globe, it reveals how history unites and shapes the identities of citizens of the three major South Asian nation-states.

Edited by Shahid Amin, Tridip Suhrud and Megha Todi, Thumb Printed: Champaran Indigo Peasants Speak to Gandhi (National Archives of India) focuses on a vast ‘peasants’ archive’ of testimonies from Bihar in the run up to the satyagraha or non-violent agitation in 1917 against forced indigo cultivation. This volume goes beyond Gandhi to recover the peasants’ own voices.

‘A pacy narrative of two stormy lives’

Catherine Fletcher, Professor of History at Manchester Metropolitan University and the author of The Beauty and the Terror: An Alternative History of the Italian Renaissance (Bodley Head, 2020)

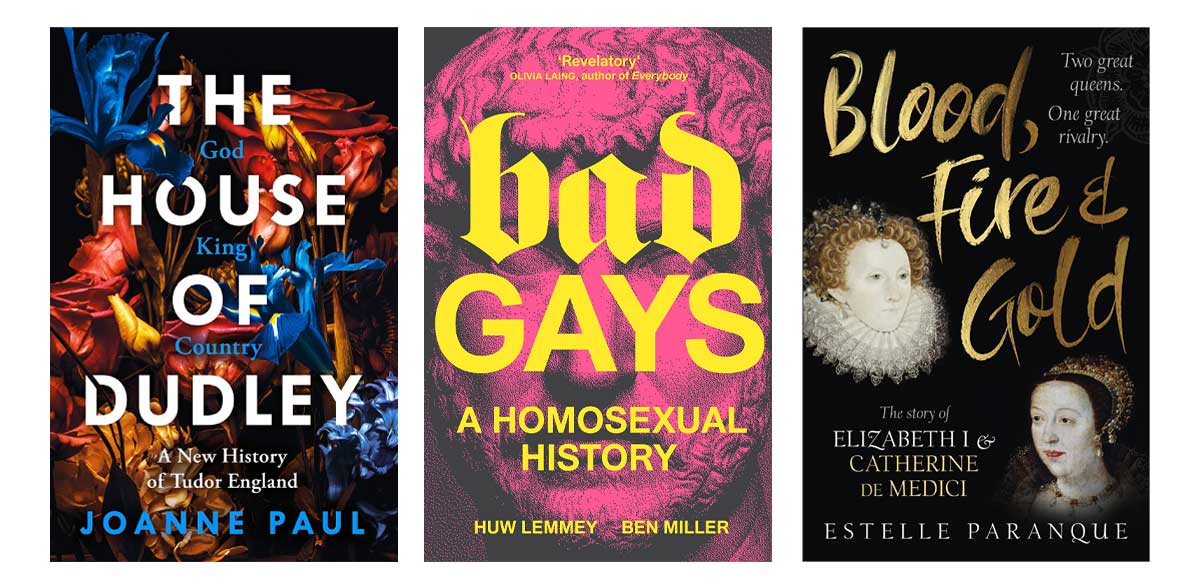

It’s tempting to think there’s nothing more to say about the Tudor monarchs, but two books this year deliver fascinating insights. Joanne Paul’s The House of Dudley: A New History of Tudor England (Michael Joseph) tells the story through the eyes of the dynasty accused of trying to supplant them, while Estelle Paranque’s Blood, Fire and Gold: The Story of Elizabeth I and Catherine de Medici (Ebury) is a pacy narrative of two stormy lives.

Two new queer histories also caught my eye. For historical perspective on the culture wars, Kit Heyam’s Before We Were Trans: A New History of Gender (Hachette) is an intervention into the debate about how to write past lives without imposing modern understandings. And for an antidote to assumptions that anyone oppressed must be the good guy, I recommend Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller’s Bad Gays: A Homosexual History (Verso).

‘The inclusion of the voices of Chinese gold miners is groundbreaking’

Gao Yunxiang, Author of Arise, Africa! Roar, China! Black and Chinese Citizens of the World in the Twentieth Century (University of North Carolina Press, 2021)

Two ‘grand masters’ of Asian American Studies have produced provocative recent books. Mae Ngai’s The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes and Global Politics (W.W. Norton) takes the well-known story of Chinese gold miners in 19th-century California and expands it to incorporate global movements of people and capital from California to Cape Town. Ngai’s inclusion of the voices of Chinese gold miners is groundbreaking.

Erika Lee’s America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States (Basic Books) deftly contrasts anti-immigrant fervour with America’s vaunted claims to be an asylum to the world. Lee’s brisk, engaging and often personal prose describes anti-Catholic sentiment in early America, white terror against Chinese Americans, campaigns against Mexican workers and contemporary Islamophobia. Lee concludes that xenophobia is a direct challenge to democracy.

‘A provocative exploration of Holocaust memory’

Rhys Griffiths, Co-Editor, History Today

The protagonist of Yishai Sarid’s The Memory Monster (Serpent’s Tail) likens modern history to ‘a terrifying waterfall rumbling with awful ferocity’. Narrated by a tour guide for Israelis visiting Polish concentration camps, the novel – first published in Hebrew in 2017 – takes the form of a letter to the Chairman of Yad Vashem describing the acute impact of near constant psychological proximity to the Holocaust. Unflinching – at Majdanek we hear students say ‘that’s what we should do to the Arabs’ – it’s a provocative exploration of Holocaust memory in a moment of generational shift.

It’s 30 years since the breakup of Yugoslavia and 30 years since Bosnian-German writer Saša Stanišić left Visegrád as a refugee. His memoir Where You Come From (Jonathan Cape) is exceptional, culminating in a ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’. Post (Yugoslav) war fiction deserves a bigger audience: see also Croatian author Robert Perišić’s No-Signal Area (Seven Stories Press) in which capitalism descends on an unnamed Balkan country revealing unhealed war wounds and putting its citizens ‘on display as people in defeat’.

Source: History Today Feed