The Indelible Hulk | History Today - 5 minutes read

In three couplets, American revolutionary Philip Freneau lambasted a new type of prison:

The various horrors of these hulks to tell

These Prison Ships where pain and horror dwell

Where death in ten fold vengeance holds his reign,

And injur’d ghosts, yet unaveng’d complain;

This be my tale-ungenerous Britons, you

Conspire to murder those you can’t subdue—

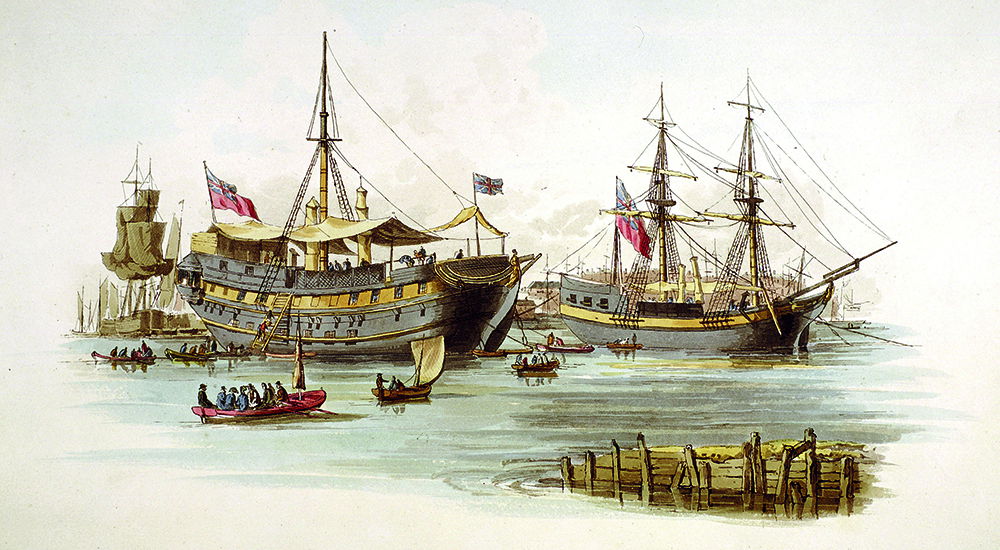

A prison hulk – a ship not seaworthy enough for full-service – was Freneau’s accommodation for six weeks.

Fortunately for Freneau, his compatriots’ efforts would soon banish the British and their hulks from America’s shores. However, American independence did not end the hulk; it took it worldwide.

Prison ships sprang up on the Thames as an alternative to transportation when prison overcrowding became inescapable. In 1823, when overcrowding on the hulks became noticeable, the same hulks were used to transport and house men overseas, as far as Gibraltar, Bermuda and Australia. The hulks had become a solution to another issue.

Iron ships and steam power were transforming navies and creating a need for investment at dockyards. Political and moral upheaval, with the loss of the New World and the abolition first of the slave trade and then of slavery, played their part too. It is easy to see how the cheap labour offered by the hulks might appeal on economic grounds.

In Bermuda, this process can be traced particularly closely. With the advent of American independence, the Royal Navy was forced to reconcile itself to a new geographic reality. In 1818, Bermuda became the headquarters of Britain’s North America Station. However, a lack of labour was a major problem in constructing a base of a size and quality commensurate with its new status. When the first convicts arrived in Bermuda in 1824, they quarried and cut some of the island’s oldest and toughest limestone into the Royal Naval Dockyard, a defensive hub of international renown and significance.

The men who were put to work went unrewarded, save for a small allowance payable upon release. And in Bermuda, unlike other colonies, there was no prospect of convicts staying on.

Conditions aboard prison hulks were bleak, with prisoners crammed together, manacled constantly and, especially when transported overseas, ravaged by extreme heat and tropical disease. Fatality rates were high, up to one in four after an outbreak of typhus on the Woolwich-based Justitia in the late 18th century, and little better half a century later in Bermuda, where conditions were regarded as among the worst of all the hulks. During the day, there was little rest, with long days labouring on public works, dredging, hauling and building. An army of unskilled workers was also unsurprisingly susceptible to injury or worse. Limbs snapped and were amputated. As late as 1847, rumours abounded of men left to die to serve the anatomists. Wardens could be brutal. Aboard the Success, a hulk in Hobson’s Bay, Australia, some prisoners received up to a hundred strikes from a cat-o’-nine-tails.

That men tried to escape, as immortalised in fiction by Charles Dickens’ Abel Magwitch, is unsurprising. Some went further. When John Price, the Inspector-General of Penal Establishments in Victoria, was murdered by a group of convicts from the Success in 1857, it proved a turning point. The Weekly Irish Times pulled no punches:

His murder was the direct means of leading to the abolishing of the hulk system in Australia, and more than one Australian paper stated openly that as he had sown the wind he had reaped the whirlwind.

An investigation, as well as a mass hanging of the murderers, followed, marking the beginning of the end of a practice that was increasingly besieged by opposition.

Worries about recidivism had long gnawed at the system’s support. The Danish adventurer Jørgen Jørgensen, self-proclaimed ‘Protector’ of Iceland, who was transported to Australia in 1825, called the hulks ‘nurseries of deep crime’, writing that ‘those who have been discharged from them have overrun England and spread vice and immorality everywhere in their track’.

He was not alone in his suspicions. Patrick Colquhoun, the father of preventative policing in England, lamented the indiscriminate mixing of hardened and petty criminals on hulks and the impact this had on reoffending rates.

In 1860, three years after hulks had been decommissioned in Britain, the Earl of Carnarvon tabled before Parliament the words of the Bermuda-based chaplain William Melbourne Goulding, who reported that:

It is my painful conviction, after some years’ experience of the matter, that the great majority of the prisoners confined in the hulks become incurably corrupted, and that they leave them, in most cases, more reckless and hardened in sin than they were upon reception.

By this time, the peak years of the system had long passed, and transportation was becoming much less common. Hansard also records the admission of a lack of suitable candidates for prison administration overseas.

Perhaps the greatest cause of the end of hulks, however, was the admission in the same debate that work in Bermuda was very nearly completed. Three years later, Bermuda’s hulks were gone.

Moral concerns might not sink a working system, but they might triumph when the hulks’ work was almost done.

Edward Ferrari-Willis is a freelance writer and an editor of historical fiction.

Source: History Today Feed