The Abode of Madness | History Today - 5 minutes read

The term no man’s land comes with clear connotations of war, especially trench warfare on the Western Front. Yet the concept of ‘none man’s land’, nanesmaneslande, first appears in the Domesday Book of 1086, referring to the area that is now Hyde Park in London. The phrase as we know it today arose in the mid-14th century as nomanneslond, referring to what the Oxford English Dictionary describes as ‘the name of a plot of ground lying outside the north wall of the city of London, the site of a place of execution’. It was also used more generally to describe land that was disputed, such as an area in Herefordshire that was contested between the monasteries of Westminster and St Albans in the 1400s and, as a result, is still called Nomansland Common today. It was also used to indicate areas considered beyond the realms of the law, often associated with loss or death, such as mass burial grounds or plague pits.

It is during the 20th century that the term took on its military connotations, most often associated with the First World War and the area of land between opposing armies that was unoccupied or uncontrolled. Often only several yards wide, these no man’s lands of the Western Front were, according to poet Wilfred Owen, ‘like the face of the moon, chaotic, crater-ridden, uninhabited, awful, the abode of madness’.

The term was first used during the First World War by Major General Sir Ernest Dunlop Swinton in his short story ‘The Point of View’. He describes the flames and searchlights highlighting:

In that wilderness of dead bodies – the dreadful ‘No-Man’s-Land’ between the opposing lines – deserted guns showed up singly or in groups, glistening in the full glare of the beam or silhouetted in black against a ray passing behind.

Both during and after the war, these no man’s lands provided the backdrop for art and literary works, including Erich Maria Remarque’s novel All Quiet on the Western Front (1929) and Storm of Steel (1920) by Ernst Jünger. The war poet Ewart Alan Mackintosh, killed at Cambrai in 1917, described these areas as where ‘death or capture may lurk unseen’ and Robert Beckh wrote: ‘We press with a noiseless tread, Thro’ no mans land but the sightless dead.’

Just as the term developed a meaning for the men at the Front, these works meant it reached the minds of civilians and the families of those who were facing the horrors of war in foreign fields. They have embedded the term and these images in the collective memory to the present day and inform our ideas of the First World War.

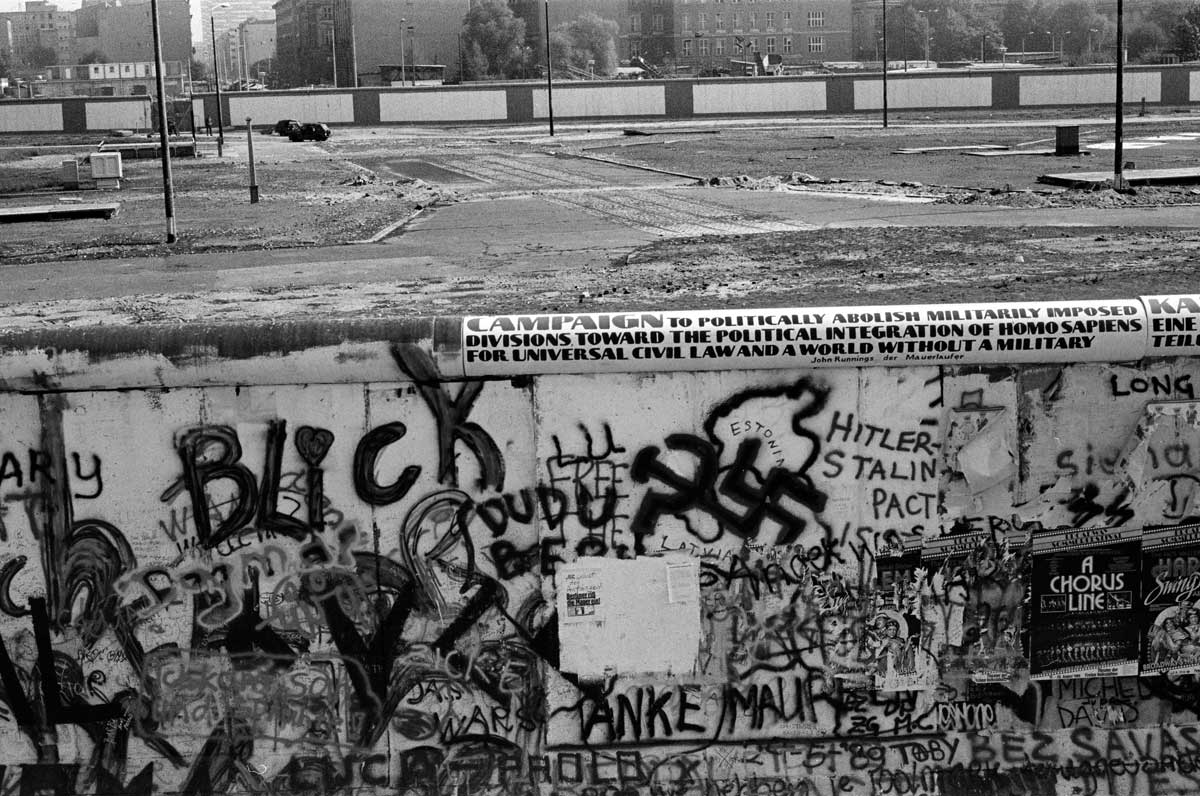

Since 1918, no man’s land has kept its military connotations, often representing militarised or demilitarised borders. Throughout the Cold War, the term was used to describe areas across the Iron Curtain, where miles of uninhabited land, officially owned by the countries of the Eastern Bloc, fell within a militarised zone. These areas were often guarded by watchtowers, wire fencing and minefields, preventing civilians from fleeing to the West. Similarly, the term is often used to describe the Cyprus Buffer Zone, established by the United Nations. In 1974, civil war between Greek and Turkish factions on the island led to a coup by the Cyprus National Guard and then to Turkish military intervention. The UN set up a 180km-long buffer zone, cutting through the capital, Nicosia. Once heavily patrolled, it prevented crossings from one half of the island to the other.

The term has taken on further applications throughout the 20th century, being used to describe areas that are inhabited but whose inhabitants are seen as ‘lawless’ or beyond the realms of the law – more akin to its medieval usage. These are often poverty-stricken areas, such as a strip of land near Wilmette, Illinois that took on the name between the 1920s and 1940s. Money had poured in during the 1930s to develop the land and build a hotel, but when funds ran dry the area filled with casinos, liquor stores, ice cream and hot dog stands and small fireworks shops. It quickly became a ‘slot-machine and kino sin centre’ – a place of depravity that, according to the Chicago Tribune, ‘was an area unpoliced, unrestricted and under no municipal control’. It was seen as so lawless that, when a fire broke out at one of its casinos in the early 1930s, neither of the neighbouring fire departments offered assistance or claimed jurisdiction over the land, leaving the building to burn to the ground.

Over its millennium of use, no man’s land has had military, environmental, cultural and even metaphorical uses, often being applied in a political or legal sense, but still brings with it connotations of fear, hopelessness, loss, lawlessness or death. It continues to spark images of the First World War and, thanks to modern films, images of brave men going over the top into grim and lifeless stretches of land to fight the enemy have stood steadfast.

In the future, could no man’s land also signify hope? The areas around sites of nuclear disasters such as Chernobyl that have been given the name have flourished in the absence of people, as natural ecosystems have sprung back to life.

Similarly, after the First World War, even as the term gained prominence, the French government created the Zone Rouge, turning the once barren, devastated battlefields of Flanders and the Western Front into beautiful open countryside and areas of conservation, covered with poppies and wildflowers and home to vast war cemeteries that enable future generations to remember those who lost their lives.

Maria Ogborn has an MA in Military History from the University of Birmingham.

Source: History Today Feed