Words and Deeds | History Today - 6 minutes read

In 1988 the publication of The Satanic Verses, a novel by the Indian-born British writer Salman Rushdie, propelled an obscure and contentious historical incident into the centre of a global debate about free speech and blasphemy. It was not the first time that the so-called ‘Satanic Verses’ had caused controversy; their veracity and meaning were fiercely debated within medieval Islamic scholarship, centuries earlier.

In the Muslim scholarly tradition the ‘Satanic Verses’ incident is known as the ‘Story of the Cranes’. It narrates the occasion when the Prophet Muhammad mistook the whispers of Satan for divine revelation, leading Muhammad to recite false verses of the Quran in praise of the pagan idols of seventh-century Mecca. The controversial phrase ‘Satanic Verses’ was coined by the Scottish orientalist Sir William Muir in his 1858 biography The Life of Mahomet.

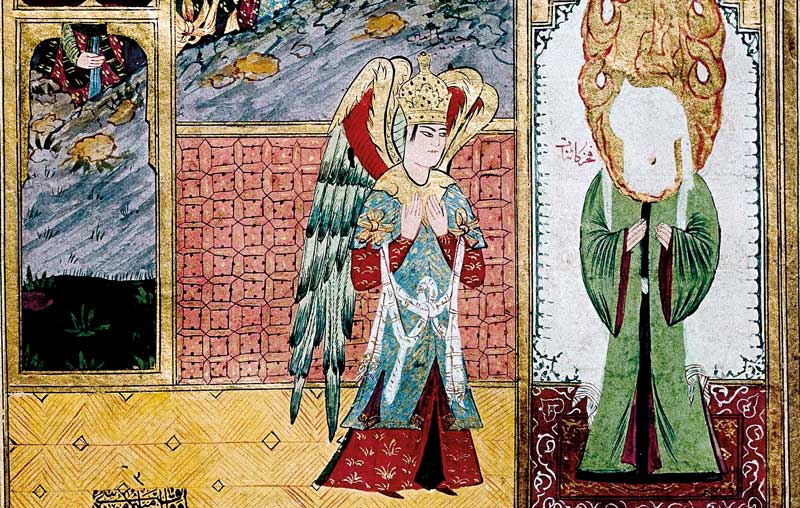

There are at least 50 reports from the first two centuries of Islam that describe, in detail, the occasion when Muhammad supposedly mistook the deception of Satan for the command of God. These reports are known as riwayahs (‘telling’ or ‘recounting’). Most riwayahs follow the same general contours – with some divergences – as the one recorded by Ibn Ishaq (d.767) in one of the earliest and most widespread biographies of Muhammad. Ibn Ishaq describes how, overcome by the struggle of preaching monotheism to a pagan society, Muhammad came under pressure from his local tribe. Satan exploited the situation by feeding him false revelation. Muhammad joined the pagan Arabs in the veneration of their idols, Lat, Uzza and Manat. The pagan Arabs rejoiced that Muhammad and his Muslim. followers granted their religion some respect. Muhammad was later reproached by the Archangel Gabriel, who told him: ‘This is not God’s revelation.’ God forgives the disheartened Muhammad and reminds him that previous prophets have fallen into traps set by Satan.

As the late Harvard scholar Shahab Ahmed observed, the ‘Satanic Verses’ incident was recorded by virtually every biographer of Muhammad in Islam’s first two centuries. The earliest Muslim exegetes – specialists who wrote commentaries on the Quran – also recorded the incident. Some of them took religious instruction from the senior Companions of the Prophet. Six of the most prominent exegetes recorded the incident on the authority of Abd Allah Ibn Abbas, a close and learned companion of Muhammad. During Islam’s first 200 years the incident was widely reported in almost every important intellectual centre in the Islamic world. It was accepted as true historical memory throughout Medina, Mecca, Basra, Baghdad, Samarkand and Sanaa.

Why was this humiliating incident deemed true? By the time the theologian Ibn Taymiyyah admitted to the soundness of the ‘Satanic Verses’ in the 14th century, he did so very much against scholarly consensus. To understand why early Muslim authorities accepted the ‘Satanic Verses’, we need to understand why later Muslims rejected it.

For those later Muslims the incident was historically spurious and theologically abominable for two reasons. First, Muhammad was protected by God; he was, therefore, infallible and not prone to mistakes. Second, the reliability of the early recorders of the incident was dubious because it relied on doubtful evidence. But the question remains: why did early Muslims transmit such a story if it was an invention of fecund imagination? To answer this, we need to understand that the early memory of Muhammad and his community was preserved in three different, often disagreeing, methods of recording history: Hadith, Sirah and Tafsir.

The early biographers and exegetes belong to the Sirah and Tafsir school of history. Sirah describes the biographies that record the life and career of Muhammad, while Tafsir is the corpus of exegetical material on the Quran. The Hadith was a wholly different cultural and intellectual project. How Muhammad came to be remembered and portrayed in medieval and later accounts depended on different modus operandi and religious motivations. Some biographies were concerned with his expeditions; others were keener on his miracles and piety. For others it was important to remember Muhammad as a beautiful and exemplary model for life.

The aim of the Hadith movement was, as Ahmed writes in Before Orthodoxy, ‘to establish legal, praxial, and creedal norms through the authoritative documentation of the words and deeds of Muhammad’. Hadith scholars sought material that would form the basis of Islamic law. The collections of the sayings and words of Muhammad, known as the Hadith corpus, formed the bedrock of Islamic law. Law in Islam allows human beings to acquire moral traits beneficial to their life and character. For pious believers, law can be epitomised as a journey towards moral perfection by imitating the example of Muhammad. Hadith, then, became storehouses for a great many written and oral statements by Muhammad, the basis of the rules that regulated the lives of Muslims.

The Hadith project scrutinised the validity and credibility of the historical memory of Muhammad in relation to legal matters, based on a thorough process of investigation. The ‘Satanic Verses’ incident was not included in any of the canonical Hadith collections. It was deemed inauthentic and incongruent with the theological project of the Hadith movement, which required the Prophet to be infallible, beyond reproach in the realm of religious matters.

The scholars of Sirah and Tafsir, however, were not primarily concerned with establishing norms of religious law and practice for Muslims. Rather, they sought to construct ‘a narrative of the moral-historical epic of the life of Muhammad in his heroic struggle to establish divine religion’, as Ahmed put it. In the Sirah, Muhammad is born an orphan, ‘singled out by God to be His Messenger and charged with the mission of leading his people out of the darkness of idolatry to the salvation of monotheism’. The Sirah is, therefore, a deliberate attempt to portray an austere and humanised Muhammad, who labours to overcome life’s great calamities in order to make monotheism and divine religion supreme. In this telling of Muhammad’s life, the ‘Satanic Verses’ incident adds to a heroic story of peril, persistence, suffering, fortitude, faith and triumph.

Ahab Bdaiwi is University Lecturer in Arabic and Medieval Philosophy and Late Antique Intellectual History at Leiden University.

Source: History Today Feed