The End of the Templars - 2 minutes read

Less than 25 years after the fall of Acre in May 1291 – the last, decisive defeat for the Crusader states – the Knights Templar fell too.

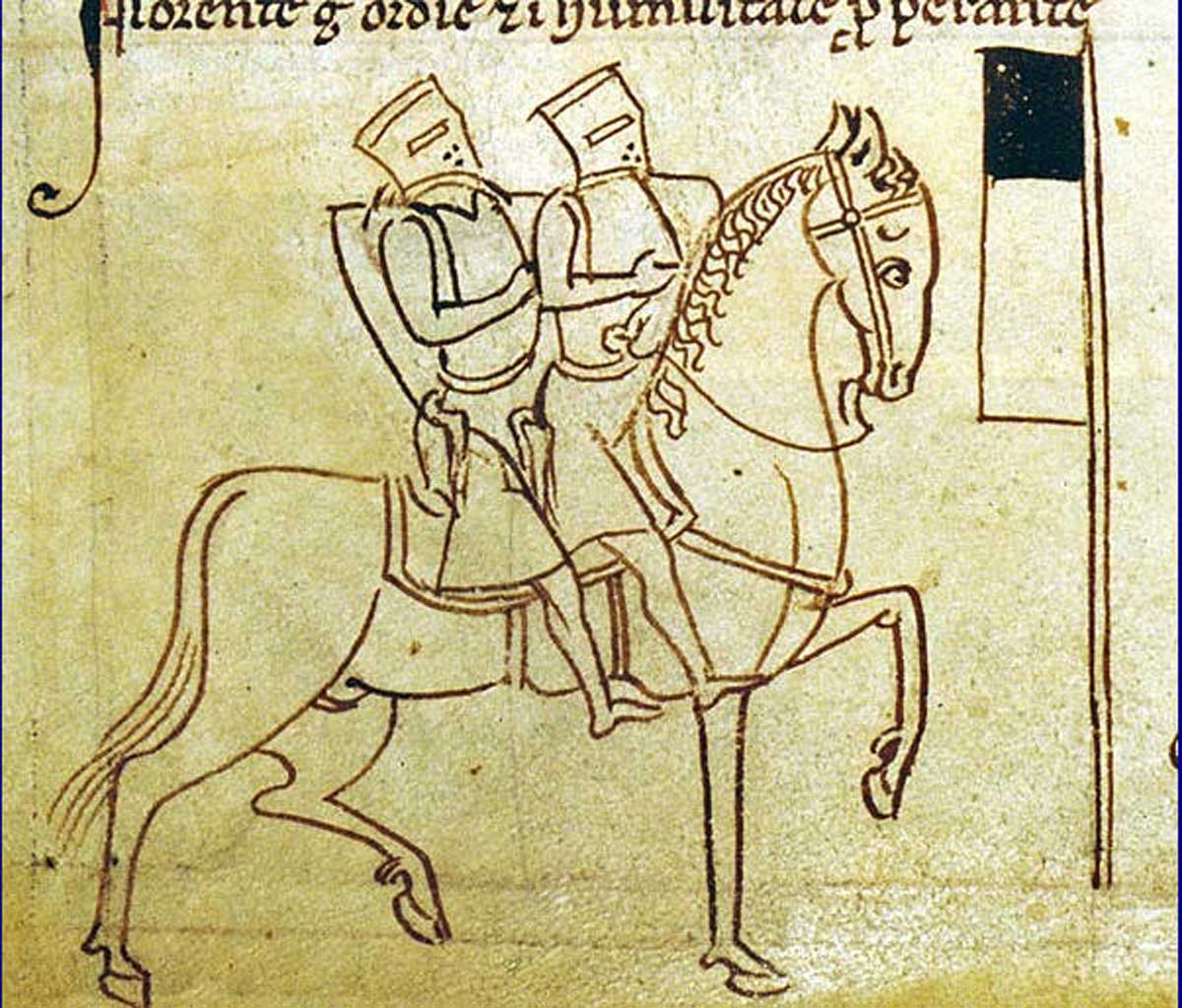

Founded around 1119, they began modestly as military escorts for the Christian pilgrims flocking to the newly conquered Holy Lands. It was commonly said that the order had only nine knights for its first nine years – a figurative truth that also nods to the way in which the order always seems to have had a mystical identity alongside its material one. Myths and fantasies accreted to it; arguably, they were its downfall.

The great Cistercian scholar Bernard of Clairvaux, an early supporter, acclaimed them as ‘a new sort of knighthood’, but they were a new sort of monasticism too, one which – counterintuitively – privileged violence over contemplation. ‘Whether one dies in bed or in war, the death of his saints will doubtlessly be precious in the sight of the Lord’, Bernard wrote. ‘However, the more precious is death in war.’

The Templars were also a new financial system. At their peak they had a network of some 870 houses and castles, and their vast reach made them the preferred choice for transferring large sums internationally. Henry III used the Crown Jewels as security for a loan. Baldwin II of Constantinople had something better: a relic of the True Cross.

In the end, it was all about money. The Templars were rich; Philip IV of France was in need. In the autumn of 1307 he pounced. The Templars were arrested and charged with blasphemy, idolatry and institutionalised sodomy. Was it true you were required to deny Christ three times and to spit on a crucifix, they were asked. Were you told, ‘If any brother of the Order wishes to lie with [you] carnally, [you] shall accept this because it is a duty’?

In Paris, in May 1310, 54 Templars who refused to confess were burned alive as heretics. The others got the message. After Pope Clement V suppressed the order on 22 March 1312, the veteran Master of the Temple, James of Molay, and another senior colleague, Geoffrey of Charney, recanted their confessions. They too were burned alive.

The true history of the Templars ends there. The mythic history was only just beginning.

Source: History Today Feed