The US Treasury’s Money Laundering Machine - 5 minutes read

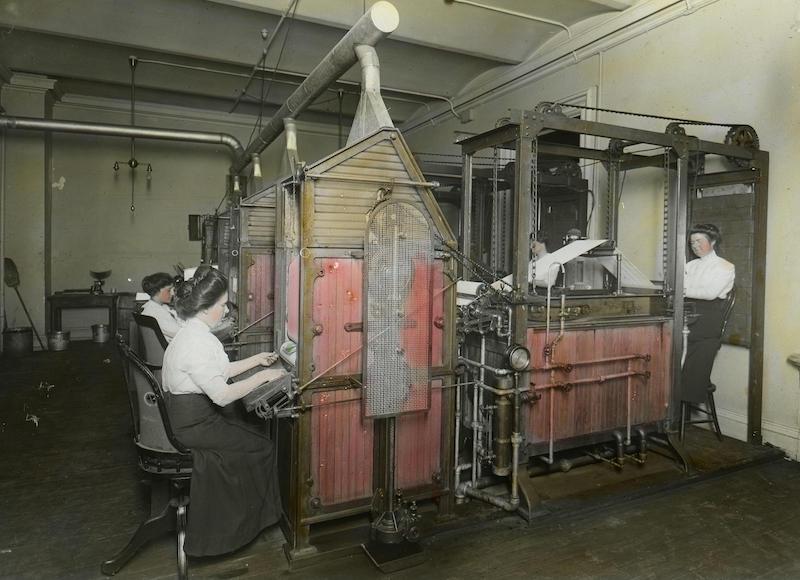

In 1910, in the basement of the US Department of the Treasury’s Bureau of Engraving and Printing, a cacophonous and cumbersome money laundering machine was installed to solve the issue of deteriorating paper money. Instead of sending thousands of soiled dollar bills to the macerator, chemist Burgess Smith invented a contraption that not only washed away the grime, but also sterilised and ironed each note, rendering them pristine and crisp.

In an April 1912 report to Secretary of the Treasury Franklin MacVeagh, Treasurer Lee McClung argued that the machine would not only give people better and cleaner money, but, by reducing the cost of printing new money, it would greatly benefit the US economy.

With the capacity to wash 25,000 notes a day, the apparatus was capable of giving new life to around 60 per cent of bills presented to the Treasury for redemption, saving, it was estimated, roughly $250,000 of annual printing costs (the equivalent of $8,100,000 today).

The demand for clean notes was monumental, or as Treasury officials stated in the Washington Times, banks ‘eat them up’. Mr Smith, on a salary of six dollars per day, was tasked to improve his machine so it could be distributed around the country and, by late 1912, his apparatus was installed in sub-treasuries and financial institutions in most major US cities.

Interest in the device soon grew on the other side of the Atlantic. On 26 September 1912 representatives of the German government visited Washington to witness the machine in action, exploring the possibility of adopting it in their country. The Japanese, French and British governments also expressed an interest in it.

The invention, however, was not immune to criticism. Cynics believed that the clean notes would encourage counterfeiters, but in an article published in the Gettysburg Compiler on 12 March 1913 Joseph E. Ralph of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing denied the possibility: ‘It has been charged in some places that the laundering of money would encourage counterfeiting, but that will not be the case.’ This, he explained, was because forgers tended to artificially soil banknotes, which would be detected during the laundering process.

It did not take long for Ralph’s words to face rebuttal. In April 1913, Senator James Edgar Martine of New Jersey sought to publish letters from 587 bank presidents and cashiers who declared that the laundered money was the ‘counterfeiters’ delight’. During a congressional hearing the Senate’s banker, Senator Reed Smoot, refused the printing of the letters, forcing Martine to withdraw his request, but an article dated 9 February 1913 in the Daily Arkansas Gazette sheds light on the bankers’ objections. They argued that cashiers across the country were unable to detect counterfeit currency, and experts of the Treasury department were no longer adept at spotting fake notes. The laundered paper felt different: it lacked the crispness of newly printed money and the evenness of colour, and was often indistinguishable in both look and feel from forged notes.

In fact, while money had been saved by the Treasury in printing expenses, it left the ‘door open’, continued the Gazette, ‘for all the crooks and counterfeiters in the country to get busy and make big hauls’. Secret service records from the time show that more attempts at creating counterfeit notes were being made than ever before thanks to the money laundering machines.

Since the Bureau of Engraving and Printing’s founding in 1862, new notes had been printed using machinery instead of manual engraving. The Gazette questioned whether this also made the counterfeiting procedure easier. It is likely that both contributed to the process. The new ink and material used for machine-printed banknotes, once washed, lost their vibrancy, making it difficult to tell true notes from false.

Bank officials believed that MacVeagh had made a terrible mistake approving the money laundering machines. He disagreed, and Ralph shared his sentiment. In the Gazette, he stated that the labour-saving devices had saved the US roughly $5,000,000 in printing costs since 1 January 1912 ($155,000,000 today).

Brushing away any unfavourable publicity, the laundry device gained a spotlight at the 1915 world’s fair held in San Francisco, taking centre stage at the ‘While You Wait’ exhibit. The Jackson Daily News wrote that ‘the treasury department’s coming display should come in for a goodly share of public approval’. But, when the US entered the First World War, Smith’s contraption faded from public attention, overshadowed by wartime concerns and new priorities.

By 1920 a Boston Globe article said that the Bureau of Engraving and Printing was struggling to meet the overwhelming demand for new paper money while an abundance of dirty and worn bills were in circulation. The laundering apparatuses that had seemed revolutionary had fallen into oblivion.

Their disuse could be due to numerous factors. The shift in the composition of paper notes from flax-based to cotton-based made it easier for citizens to launder and dry their soiled money at home, rendering the Treasury’s laundering process less necessary. This, combined with the negative media attention and the protests from bankers, seemed enough to persuade the Treasury to shut down its laundering operations. The noisiness and maintenance of the machines could have played a role as well.

The phrase ‘money laundering’ is now synonymous with organised crime. From the 1920s, mobster Murray Humphreys seized control of the cleaning businesses run by Al Capone’s Chicago Outfit gang, allegedly coining the term ‘money laundering’ as it is now commonly known. But, while certain members of the Outfit were known to be money forgers, there is no evidence to link the Treasury’s laundry machine to Humphreys’ phrase.

The term’s new meaning would not appear until 1974, when the New York Times reported that Richard Nixon had asked his aides to intervene in an FBI inquiry into ‘money laundering operations in Mexico City’. Smith’s machine is now inextricably associated with fraud, its practical – and legal – origins entirely forgotten.

Stefano Siggia is an anti-money laundering consultant.

Source: History Today Feed