Securing Antarctica | History Today - 9 minutes read

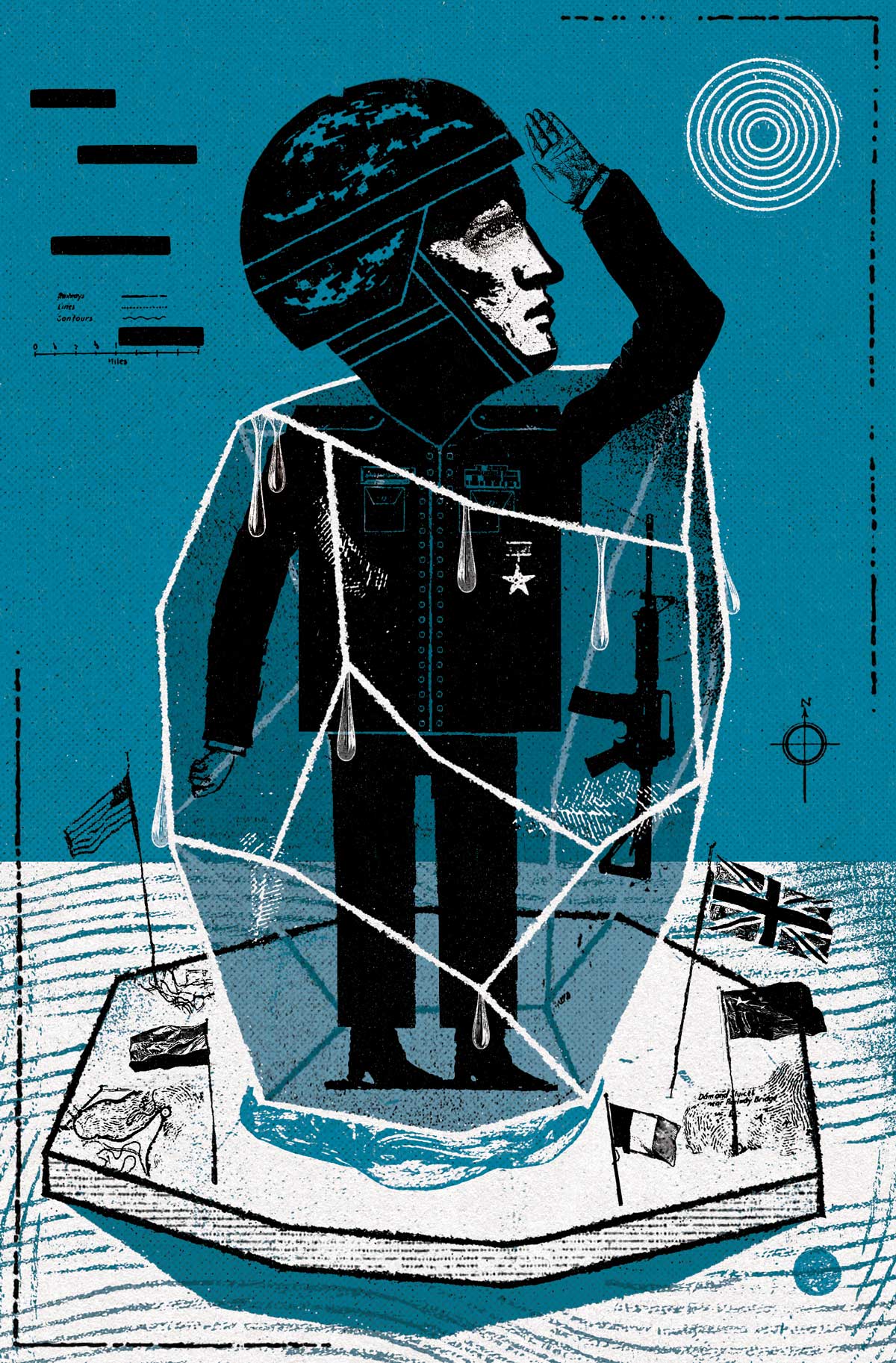

On 1 December 1959 a new treaty was signed by 12 countries, including the US, the Soviet Union, France and the UK. It was revolutionary. For the first time, in the midst of the Cold War, the then three nuclear-weapon states agreed to transform a continent into a nuclear-free zone and, along with other parties, such as Australia and Argentina, committed themselves to a new governance regime. In a series of articles, the treaty offered a shared vision for how the polar continent and its ocean should be governed. The Antarctic would be demilitarised and characterised by peaceful co-operation. Science would be a catalyst for a collective culture of collaboration. The treaty parties, mindful of Cold War antagonisms, hardwired into their new arrangements a right to inspect one another’s scientific activities.

Continental cooperation

Sixty years later, there is much to admire about the Antarctic Treaty and what it spawned, including a series of conventions, protocols and structures called the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS). From the original 12 parties, there are now over 50 signatories, including China, India and Brazil. Notably, there is only one representative from Africa: South Africa. The treaty parties have tackled issues such as mineral resources and have found ways to cooperate over fishing, tourism and environmental protection. The continent remains largely free of military activity and has endured as a nuclear-free zone.

There are, however, also concerns about Antarctic governance. One of the most pressing issues is how to balance the impulse to protect Antarctica’s environment with the desire to exploit its resources. The ownership of the continent remains disputed. Climate change continues to make itself felt on the ice, water and rock of Antarctica. Finally, there is no escaping the fact that the polar regions of the world are caught up in global geopolitical tensions, especially the growing presence of China.

The circumstances leading to the development of the treaty negotiations were mired in tension and uncertainty. One of the foundation myths of the Antarctic Treaty is that its genesis lay with the 1957-8 International Geophysical Year (IGY). The IGY was a period of global scientific investigation, involving over 60 countries working on individual and shared projects. Twelve countries committed themselves to Antarctic research though, due to Cold War sensitivities, there was less scientific activity in the Arctic region. Informing the IGY was a so-called 1955 ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ for the Antarctic programme, which stipulated that any interested party could conduct research regardless of geographical location.

What a carve up

The agreement was notable because the ownership of Antarctica was contested. Since the turn of the 20th century, seven countries made territorial claims. On the basis of prior episodes of exploratory activity, industrial exploitation in the form of whaling and sealing, alongside scientific research, this select group of countries led by the UK and its Commonwealth allies Australia and New Zealand, began to carve up Antarctica. By the 1940s, the claimant club grew as Argentina and Chile joined two other European states, France and Norway. The most contentious area of the polar continent was the Antarctic peninsula. Britain, Argentina and Chile made claim to similar territories and the two South American countries contended that their territorial interests were rooted in an imperial inheritance from the former colonial power, Spain. Complicating matters further, the US and the Soviet Union did not recognise the legitimacy of any of these territorial claims.

The thorny issue of ownership was shaped by the fact that there was and is no indigenous human population and, in the 1940s, Antarctica would have appeared to most people as remote as the Moon. Very few people visited the southern polar continent and, until the Second World War, there was no history of permanent human occupation. While German raiders attacked Norwegian whaling vessels, the war years left Antarctica by and large unscathed. What it did do, however, was usher in a new era of emerging territorial and resource competition. If the ownership of Antarctica were contested, might this lead one day to conflict? What would happen if strategically valuable minerals were discovered? If the US made a territorial claim to Antarctica would this provoke the Soviet Union to follow? Could Cold War geopolitics make itself felt on the icy wastes of Antarctica? These sorts of questions were routinely asked in newspapers around the world. Australian media was preoccupied with the emerging scientific presence of the Soviet Union in what was considered to be Australian Antarctic Territory.

Claims and compromise

Scientific planning for the IGY Antarctic dimension was made possible by compromise. The claimant states recognised that they would have to accept that the US, the Soviet Union and three other parties (Japan, Belgium and South Africa) were not going to be restrained by new countries’ claims. The US established a South Pole station and the Soviet Union, to great fanfare, located a scientific station at the Pole of Relative Inaccessibility. After 18 months of intense study, the US and others recognised that it was an open question as to what happened after the IGY.

When the US invited those 11 other IGY Antarctic parties to come together for a special conference on the future of Antarctica, there was no expectation that a treaty would automatically result in late December 1959. Even before the delegates arrived in Washington DC in October of that year, there had been preparatory meetings aplenty. And there were troubling issues still outstanding. Would the claimant states and non-claimant states be able to get around the issue of ownership? Who would be able to exploit the resources of Antarctica? Would Antarctica ever be used as a military testing ground? The signing of the treaty on 1 December 1959 was a diplomatic triumph and one which nearly did not happen, as claimant states such as Australia and Argentina struggled to reconcile their own concerns about the future role of the superpowers.

Using scientific diplomacy as the driver, the treaty did something quite remarkable. It bypassed the issue of territorial and resource ownership. Article 4 stipulated that the parties would agree to disagree. The ownership question would be suspended for now. Resources were not dealt with explicitly. The aim was to create a culture of co-operation and, after signing and ratifying the treaty, the parties agreed to meet every two years to talk about matters of common concern. Having only 12 countries helped matters and the timing was propitious because other interested parties, such as India and China, did not object to their omission. Had the negotiations occurred several years later, the outcome would have been much less assured.

Enduring hope

The New York Herald Tribune reported that the treaty was a cause for ‘enduring hope’. It acknowledged that the demilitarisation and denuclearisation of Antarctica could forge a precedent for future international relations. It is difficult to overestimate how important the ban on nuclear weapons was alongside the prohibition on military activity. While historians of Antarctica speak frequently about the catalytic power of science and scientific co-operation, it was the arms control element of the Antarctic Treaty that really underpinned peaceful governance. Article 5 of the treaty was pivotal. Southern hemispheric countries supported the treaty because they could be assured that the Soviet Union and the US would not place nuclear warheads on the polar continent. The US supported the nuclear ban because it believed it would act as an unhelpful precedent elsewhere in the world. For others, paradoxically, Antarctica was considered to be a model that might be emulated elsewhere.

With those confidence-building measures in place, the treaty parties began from the 1960s onwards to confront resource-related questions. Conventions on sealing, protection of flora and fauna, fishing and, controversially, mining were developed. Most were accepted. The proposal for mining regulation was publicly rejected by Australia and France in the late 1980s in favour of a Protocol on Environmental Protection. Mining was banned and priority was placed on developing an effective regime of environmental conservation. Tension was high in the 1980s as new players such as China and India began to make their presence felt in Antarctica and environmental groups such as Greenpeace were demanding an end to whaling and a permanent ban on mining.

The treaty parties were able to weather the political storm and deal with critics such as the UN General Assembly. Antarctica, by the 1980s and 1990s, was no longer an isolated part of the world but recognised as integral to debates about a global future.

For all the success of the Antarctic Treaty in providing a mechanism for cooperation and détente, tensions in Antarctica remain. Resource management and allocation is challenging. Debates over marine-protected areas in the Ross Sea and East Antarctica reveal the desire of some to exploit further fishing resources. China is eager to fish more intensively in the Southern Ocean. Other parties want to expand protected areas and restrain commercial fisheries. China does not accept any territorial claims made in the past and has invested heavily in science, infrastructure and economic activities, such as fishing, tourism and biological prospecting. Countries don’t always agree on what constitutes serious environmental impact. Even things like the conservation of old research huts can attract controversy, if another party thinks that it is being done for purposes other than heritage.

Climate change

Uniquely, perhaps, the Antarctic Treaty parties commit themselves to consensus. They find ways to accommodate diverse parties to their own interests, experiences and ambitions. But the future of Antarctica is tied up with wider debates about how we manage some of the remotest parts of the Earth at a time of intensifying climate change and resource pressures. For most states, the Antarctic is akin to the high seas, the Moon and the deep seabed – areas of common heritage that belong to the collective international community. But how long will the mining ban remain in place? And are disagreements in fishing and environmental conservation a prelude to potential conflict over Antarctica itself?

Klaus Dodds is Professor of Geopolitics at Royal Holloway, University of London and author of The Antarctic: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford, 2012).