Death of the Man in the Iron Mask - 2 minutes read

At the end of July 1669 the French Secretary of State for War, the Marquis de Louvois, wrote to the governor of Pignerol prison telling him to expect a new inmate, one ‘Eustache Dauger’. The instructions were unusually thorough and involved housing the prisoner in a room with double doors to prevent anyone hearing him. Only the governor was to see the prisoner, bringing him food, water and whatever else he needed. If the prisoner spoke about anything other than his needs, he was to be immediately killed.

Dauger arrived at Pignerol in late August and remained there until he had to travel with the governor to his new appointment at the Exiles Fort in Piedmont in 1681. In May 1687 the governor moved again, this time to Sainte-Marguerite, an island just off Cannes. It was during this journey that rumours began to spread that there was a prisoner wearing an iron mask to keep his identity secret. More rumours spread about who that prisoner could be, from Louis XIV’s younger twin to Charles II’s illegitimate son. Some favoured a disgraced French general or one of the participants of l’Affaire des Poisons – a scandal involving black magic and poisonings which threatened to engulf the king’s mistress.

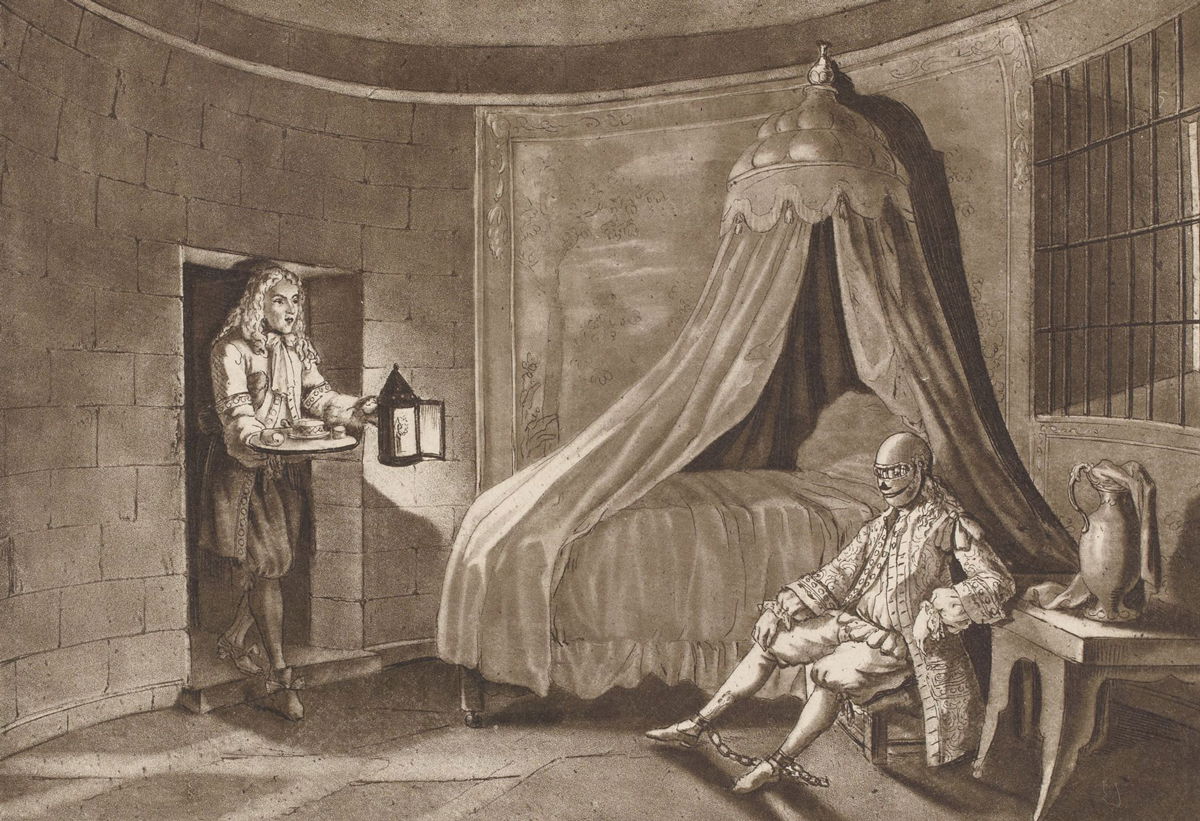

The following year the governor was on the move again, this time to the Bastille, taking Dauger with him. One of the jailers noted that the prisoner did indeed wear a mask when there was a danger of anyone seeing him, but it was of black velvet, not iron. Orders remained that Dauger was to be killed if he spoke to anyone about anything other than his immediate needs.

Whatever it was that Eustache Dauger knew, or the king thought he knew, he took that secret to his grave, dying at the Bastille on 19 November 1703. He was buried the next day under the name ‘Marchioly’, having spent the last 34 years of his life in captivity. His identity is still not agreed upon among historians.