Libraries for All | History Today - 6 minutes read

When the Manchester merchant and financier Humphrey Chetham bequeathed five parish libraries for the use of the common people in 1653, he was neither the first to do so, nor the last. He was, however, one of only a handful of people to establish public access parish libraries that the public could actually access. Others had the intention of being used by the common people but gave the distinct impression that not all commoners were made equal.

Between 1558 and 1709 around 165 parish libraries were established in England. The characteristics of these libraries were many and varied, so much so that modern historians cannot agree on what actually constituted a parish library. Evidently, they were repositories of (usually) religious or theological knowledge, although some of those founded from the end of the 17th century onwards also included secular works. Arguably an early ancestor of today’s public libraries, early modern parish libraries were often subject to accessibility issues, as founders dictated who could access them, what they contained and where they were located.

Parish library founders before and after Chetham made similar statements of intent about their prospective readers of the ‘common’ sort. In 1640, for example, Henry Bury, a Manchester-based clerk, gave £10 to the city’s collegiate church to purchase books ‘for the common use of the parish’. Unfortunately, the library seems never to have come to fruition. At the end of the 17th century, Thomas White, Bishop of Peterborough, founded a library in Newark-upon-Trent’s St Mary Magdalene church for the use of the ‘mayor, aldermen, vicar … and the inhabitants of that town’.

A far greater proportion of those who established libraries were less happy for the general public to use their books. Many founders restricted their access to the clergy, as can be seen in the cases of Lady Anne Harington, one of only a handful of female library founders in this period. She established a library at Oakham in Rutland in 1616 ‘for the use of the vicar of that church and accommodation of the neighbouring clergy’. She was joined in this by William White, who founded a library in St Mary the Virgin church in Salisbury, Wiltshire, in 1678 for the use of the vicar and his successors ‘for ever’. A library founded by Stephen Camborne in Lawshall in 1704 was also intended for use by successive vicars of the parish. Elsewhere, in More in Shropshire in 1680, Richard More established a library of volumes from his personal collection, stating his intent of increasing the learning and knowledge of local and visiting preachers, so that they could disseminate this knowledge to parishioners. It may be that, in saying this, More was making explicit the implicit expectations of other founders.

In the 1690s Roger Gillingham, a gentleman from Wimborne Minster in Dorset, augmented a pre-existing collection in the town’s minster church. Gillingham donated more than 80 volumes ‘not only for the use of the clergy … but for the use of the gent. shopkeepers and better sort of inhabitants in and about the town’. While Gillingham did implement social restrictions on the use of his books, he was evidently more willing to allow a wider range of people to use them than other founders.

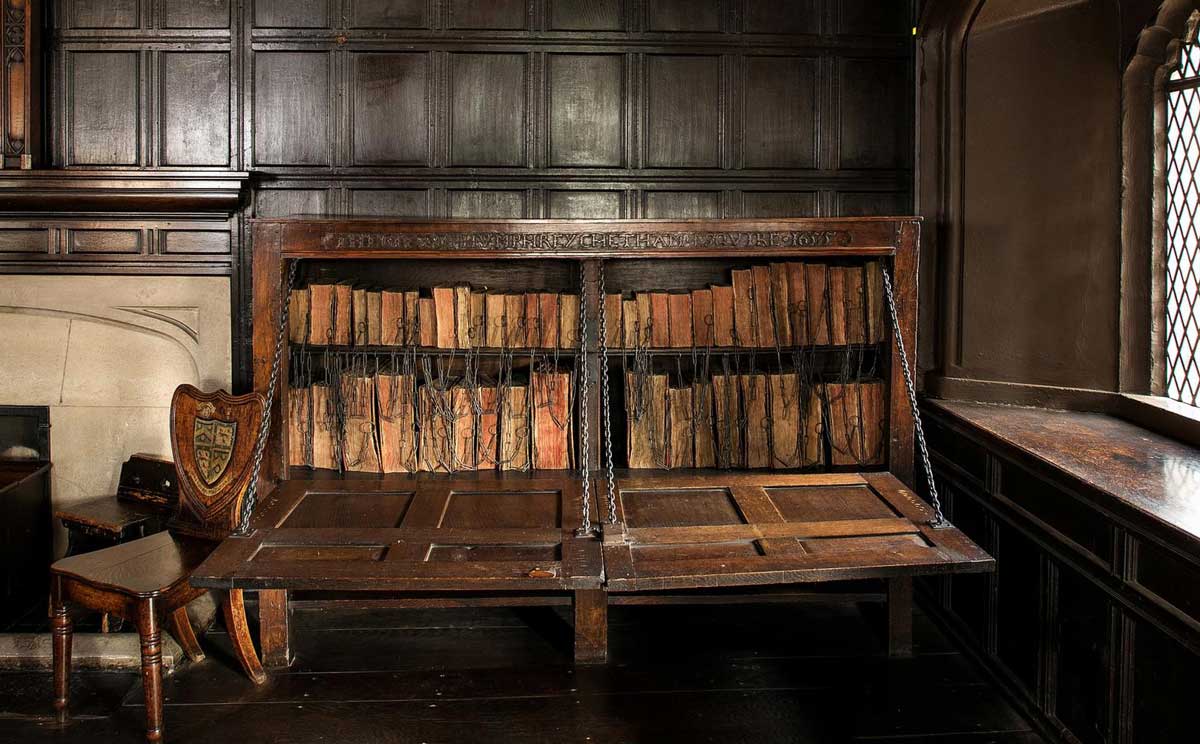

Even if certain users were not excluded from using a parish library based on their social or professional status, the physical situation of a collection could sometimes prove prohibitive to general or extended usage. Humphrey Chetham, for example, bequeathed five parish libraries to be placed in churches in the Greater Manchester area in the 1650s. These were explicitly stated to be for the use of the common people and were ordered to be placed in ‘convenient’ parts of their recipient churches. Even so, the volumes were still chained to shelves in church cupboards, which would have been immensely uncomfortable for readers using these books for an extended period of time.

Fifty years earlier, the clergyman Francis Trigge established a library in St Wulfram’s church in Grantham, Lincolnshire, for the town’s clergy and inhabitants. However, this library was placed in an upper room of the church, accessible only via a narrow spiral staircase – a physical access restriction if ever there was one. The Trigge library is not unique in this (the libraries at Swaffham and Wimborne Minster, for example, are also on upper levels of their respective churches), but in the foundation indenture, Trigge restricted access to his library even further by stipulating that the door was to be kept locked and only four people permitted to keep a key.

In their role as repositories of religious and theological texts, it is perhaps to be expected that much of this body of early modern works would be in Latin. The Chetham parish libraries once again appear to be the exception, as all the volumes in all five libraries were in English. Much more common was a combination of works in the two languages, as was the case in most of the libraries already mentioned. However, the Latin nature of many of these books excluded those without a grammar school education from using them and was therefore an implicit barrier to general accessibility.

The lack of library registers makes it frustratingly difficult to ascertain who or how many people used early modern parish libraries, and whether they were the sorts of people stipulated in library foundation documents. These repositories were not, clearly, available to all as some of their founders claimed, but their usage is attested to by the numerous marginalia contained in many of their volumes. Marginalia that provide a tantalising glimpse into the reading interests of early modern people at a parish level and suggest the important role these repositories played in facilitating that readership.

Jessica G. Purdy is Lecturer in Early Modern British History at Manchester Metropolitan University.

Source: History Today Feed