‘Every one of us has a different story’: a historic portrait of care system success - 31 minutes read

“I once was Christopher Goldsmith,” reads a poem, neatly typed out on one side of a piece of A4 paper. On the back another poem is handwritten, composed on the train into London this morning, fresh on the page. They’re part of a poem-a-day project by their author Paul Cookson, who was born in the north of England and adopted shortly afterwards by a family in Essex. “Christopher Goldsmith lived for a month,” he writes, “then quietly died, slipped away/ Almost never existed… Christopher died so that I might have life/ and have it more abundantly.”

Cookson is one of the success stories of the UK’s care system. He was the eldest of three adopted siblings, all from different families. They were happy, he says. “None of us have ever gone back to look for our birth families.” But his writing tells a subtly different story: “And so, nearly half a century later/ nearer to the end of the journey/ than the beginning,/ those questions arise/ and may remain unanswered/ but arise anyway.”

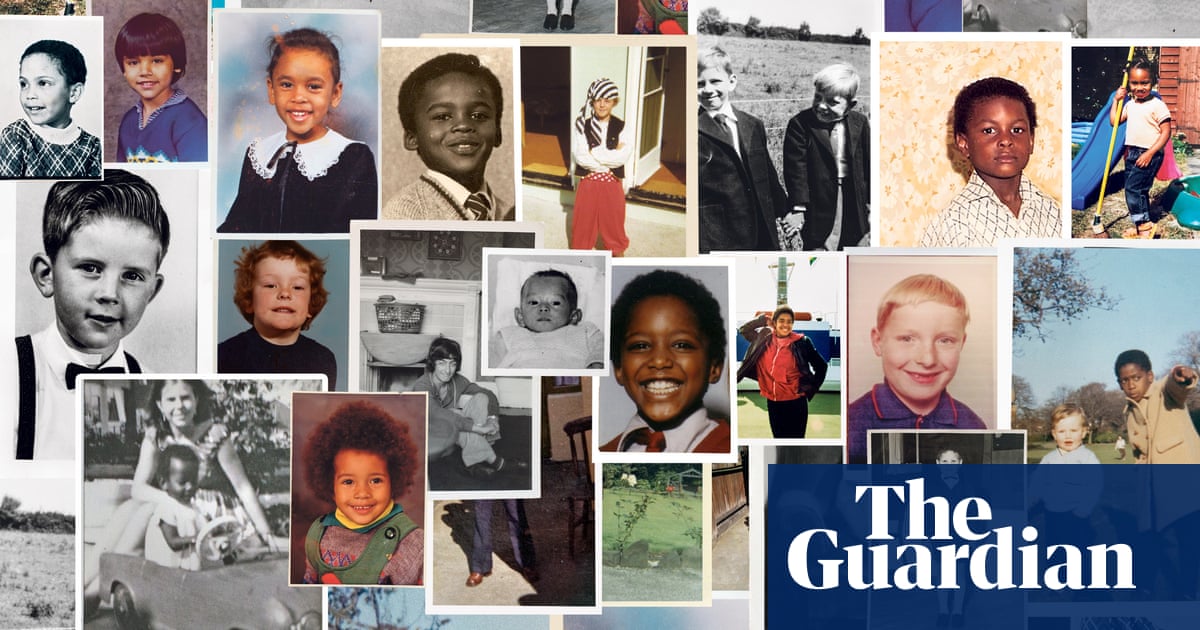

The clamour of questions is almost deafening at London’s Foundling Museum one sunny July morning, when 59 people who, for many different reasons, spent all or part of their childhoods in care, gather for a historic photocall. The project is the brainchild of poet and activist Lemn Sissay, himself a graduate of the system, who wanted to create an image of successful lives as an inspiration for the many thousands of children struggling in care today. “I’ve collected a lot of names along the way and almost everyone I asked said they would come if they possibly could,” he says. They include Olympic medallist Kriss Akabusi; novelist Jeanette Winterson; the comedian and Observer columnist Stewart Lee, and the Turner prize-nominated photographer and film-maker Zarina Bhimji.

“The way I see it, this should be something for people who are going through the system. Where they are, we have been; where we are, they can go,” says Akabusi who, like several others in the room, found his way through by joining the army. “It taught me the middle-class way of life: how to lay a table and make a bed and eat with a knife and fork. These are social graces that help us to move on.”

Antiques Roadshow star Lennox Cato has travelled up from Kent with his immaculately behaved labradoodle, Tilly; poet and playwright Louise Wallwein has come from Manchester with her support dog, Maisie, who is so overexcited that she gets through a whole packet of placatory doggy treats. Wallwein, who received an MBE in 2018 for services to spoken word poetry, had been in 13 homes before writing her first play at 17. Cato was born on the Caribbean island of Grenada and adopted as a baby by white parents in Brighton, along with his brother. He followed his dad into the antiques trade. He loved his parents, he says, “but at the time there were no black kids around. My sisters lived in London with my blood parents in a black world”.

“Every one of us has a different story,” says Sissay, beaming around the room in a shirt that is playing catch-up with the sun. Johanan Walker enthusiastically nods. “We usually get the narrative told about us so it’s nice to tell it ourselves,” she says. She was taken into a mother and baby unit as a 12-year-old mum, and had to fight to keep her daughter. Her experience of finding herself homeless and powerless after leaving care inspired her to start a campaign, calling4gr8ness.org to support young care leavers in the same predicament.

One thing many share is dark memories of the shame and stigma they suffered. “Lemn was the first person I saw on stage talking about being care-experienced and it blew my mind,” says comedian, actor and writer Sophie Willan, best known as the creator and star of Bafta-winning BBC Two series Alma’s Not Normal. “I always thought it was something I had to hide. He made me realise that it could be a strength not a hindrance.” She’s now a patron of the Bolton charity Backup North West which helped her get her first flat when she was 17.

“If I told someone I was in care, their handbag would move to the other side,” jokes Luis De Abreu, who made his escape through acting and is now principal of the dance and music theatre conservatoire he joined after dropping out of school at 15. The summer variety show he’s directing with his students at Bird College, in Sidcup, south-east London, includes a song from the pickpocketing musical Oliver!, poignantly titled Boy for Sale.

Charles Dickens’s orphan Oliver Twist is one of scores of names plastered over the walls of the room where the volunteers gather for coffee and biscuits before the shoot, along with James Bond, Jane Eyre, Han Solo and Huckleberry Finn. The installation, Superman Is a Foundling, is another of Sissay’s initiatives, drawing attention to the ubiquity of the orphan in popular culture, and it momentarily shocks the poet and performer Luke Wright to find his own history reflected in a literary trope. “I’m not sure what I think of this,” he says, anxiously, before concluding that, if Lemn did it, it must be OK.

There are a lot of big emotions flying around the room. Several people point out that they are the lucky ones – anyone who has been in a care home will know many who fell by the wayside. Ben Ashcroft, the author of a memoir titled Fifty-One Moves, was nearly one of them. That’s the number of times he was relocated between 11, when he and his brother were abandoned by their mother, and 17, when he decided he had to pull himself together. During that time he also became a drug addict and notched up 33 criminal convictions, he says. He’s now a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and founder of a campaign group Every Child Leaving Care Matters.

In a sea of brilliantly coloured fabrics – never has clothing seemed more important to the story we tell of ourselves – TV producer and editor Janet Lee looks particularly confident in jazzy reds, hot oranges and cheeky pinks. But don’t be fooled, she says. “If we spent long enough with each other, we’d probably all start crying. Fortunately we’re all busy people, so we have to rush off.” And suddenly they’re all gone, a fleeting crowd of one-offs, whose generosity with their time and their stories has created an indelible image.

“My care experience was lifesaving,” says Antiques Roadshow expert Ronnie Archer-Morgan, who recently published a memoir called Would It Surprise You to Know?. “My home situation was dire. My mother had schizophrenia, I had a stepfather who was very violent to my mother and to me. I wanted to be in care to get out of that situation.” His experience in children’s homes and foster families between Surrey and Lancashire was “excellent. I felt incredibly cared for and looked after.”

When Paolo Hewitt was researching his care memoir, The Looked After Kid, in his early 40s, he went back to Burbank children’s home in Woking, where he lived from 10 to 18, and realised that “it was actually a great experience”, especially compared with the dismal years in foster care that preceded it. “I learned a lot about life, about loyalty, about being non-judgmental. It had its pitfalls,” he says, “but it was unique.”

Alex Wheatle grew up in care in the notorious Shirley Oaks children’s home in Croydon – “a very lonely existence,” he says. As depicted in Steve McQueen’s TV series Small Axe, he was sent to live in Brixton, where his involvement in the 1981 uprisings led to his incarceration aged 18. “In prison I became an avid reader,” he says – an experience that paved the way for his career as a novelist.

In and out of care from the age of five, Stanley J Browne says his “horror story” began aged eight, when he was separated from his siblings and fostered off to Nottingham. He rebelled against the system and later ended up in detention centres and prisons, dealing with drug addiction. His autobiography, Little Big Man (out 14 October), describes how he turned his life around to become an actor and musician.

A decade ago, Clare Gorham was “very much pro” transracial adoption. “I would have said that the only thing a child needs is love,” she says, reflecting on her own experience of being happily adopted by her white family in Wimbledon in 1966. “Now my mindset is slightly different. I still think love is the most important thing. But it’s a bit of a B-movie of an existence. My parents were amazing, but their colour-blind approach wasn’t representative of society’s view of me.”

“There are at least two kinds of narratives about being in care,” says Sylvan Baker. “One is piteous, the other heroic. What happens if you want to be neither? If you just want to be?” Baker was transracially fostered from 11 days old. “I know I was lucky, I was loved,” he says. “But I felt different. I was different. I was in care.” He didn’t disclose his own experience to anyone at university until he co-founded a participatory research project called The Verbatim Formula in 2015. “It’s listening to care-experienced young people I’ve been working with that has empowered me to talk openly about it.”

Lord mayor of the City of Manchester

Donna Ludford applied to become lord mayor of the City of Manchester “to raise aspirations for young people in the care system”. She had a deeply unsettled childhood, moving between foster families and children’s homes from the age of six months, after her parents were badly injured in a motorcycle accident. Ludford began as a cleaner at Manchester city council before working her way up, earlier this year, to lord mayor. But success is “not about being the lord mayor,” she told a group of care leavers recently. “It’s about thriving in life and doing what makes you happy.”

Zarina Bhimji was taken into a children’s home at 14, then a foster family. The experience was marked by contradictions relating to her race and religion: “I remember I had chickenpox and I couldn’t go to the mosque, but we were allowed to go and see the Queen as she was visiting the town.” Encouragement from teachers spurred her on to become an artist (she was nominated for the Turner prize in 2007). “It was about having support and confidence, and knowing what is possible,” she says, “I didn’t even know what an artist was.”

Adopted as a baby, Jeanette Winterson grew up in a strict Pentecostalist family in Lancashire. She left home at 16 after coming out as gay – an experience depicted in her 2011 memoir, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?

Author, broadcaster, chancellor of the University of Manchester

Born in Wigan to an Ethiopian mother, Lemn Sissay was placed in foster care as a baby, and sent aged 12 to the first of a series of children’s homes. Later, while piecing together his origins, he discovered that his mother had pleaded for his return and been denied by social services. Sissay has spoken out about his care experience and its many traumas throughout his career as a poet and broadcaster.

When Allan Jenkins embarked on his gardening memoir Plot 29, he found himself writing about the “helplessness of seed” just three paragraphs in and was prompted to revisit his unsettled past, growing up in foster care in south Devon with his older brother Christopher. The memoir was warmly received, though Jenkins, who edits Observer Food Monthly, has mixed feelings about becoming a figurehead for care-experienced people. “Sometimes, if you’ve had my childhood, you try not to be defined by it,” he says.

Aged eight, Richard Bramble and his older brother Greg, also featured, moved in with a foster family near Leamington Spa. “Overall, the experience was good,” he says, “but you don’t feel like you’ve really lived your childhood.” Even though his new catering business is thriving, Bramble often feels impostor syndrome. “It’s like, should I be receiving all of this, should I even be doing it?” he says. “I just have to keep mentally strong and reverse those doubts.”

Participation and projects lead at Pure Insight and business owner

Natalie Hirst spent eight years living in foster care in Greater Manchester and had a mixed experience, but her resilience helped her to develop the strength and skills to overcome many challenges. “My experience has taught me the importance of having kind, supportive adults in the lives of children in care to help them feel safe, cared for and treated like one of the family,” she says. “These experiences have shaped who I am today, an independent woman, passionate about my career and working with local authorities in Greater Manchester to ensure every young person has a voice, choice and control over decisions made about them.”

Psychodynamic psychotherapist and director of Integrated Minds and Artists on the Couch

“The view of care leavers is typically: unable to achieve a higher education, expected to fail in life,” says Michelle Brown, who went into care at 11 and was “hugely let down” by her local authorities – she was left on the streets aged 15 after one of her foster carers relocated. “Many of us who stood at the Foundling Museum have had to battle our way through systemic failures and discrimination. Today we stand proud as care leavers and remove society’s stigma.” Brown defied expectations by progressing to university and getting a Masters. She is now a psychodynamic psychotherapist and the director of two companies.

When he was four, Kriss Akabusi’s parents returned to Nigeria, leaving him alone in the UK with his younger brother. They moved between several foster placements before entering a children’s home. Akabusi joined the British army aged 16 and later embarked on a glittering athletics career as a sprinter and hurdler.

In care from 11 to 17, Ben Ashcroft moved 51 times “between foster parents, residential care, secure units, secure training centre, and finally a young offenders’ unit. I was a very challenging and complex young person.” His memoir about that time, Fifty-One Moves, is now taught at universities and Ashcroft is a founding member of the campaign group Every Child Leaving Care Matters. “I’ve put a great amount of my own time back into trying to improve things for other people.”

“It destroys you as a person, the amount of anxiety you develop from always expecting something to go wrong in your life,” says Tarell Mcintosh, who became homeless after two local authorities in south London failed to properly care for him. Mcintosh managed to make it to university and now runs a Caribbean restaurant, Sugarcane London, in Wandsworth, but he remains scarred by his experiences. “You just get used to battling with everybody all the time, and you always have your guard up. It’s really horrible.”

Because her care experience happened so early – she was in and out of a foster home in east London until the age of five – Siroun Button never really thought of herself as somebody who’d been in care. “Now I’m starting to realise that it did really have an impact on me,” she says. To help others like her, Button has co-founded calling4gr8ness.org, a programme supporting care-experienced young adults in the creative industries.

When Lennox Cato and his older brother were adopted by a white family in Brighton, they stayed in touch with their birth parents, who had come over from Grenada. “They were just friends,” says Cato, now an expert on Antiques Roadshow. “They’d come down to see us and say hi. What kept us stable is that we knew we had two mums and dads.”

Lucy Sheen was one of 106 Hong Kong Chinese foundlings who were adopted by white British families in the 1950s and 60s. “Where I grew up, in a very white conservative area, there weren’t any other people who looked like me for the best part of 16 years,” she says. Sheen has made a documentary about her experience, a powerful study of cultural displacement and linguistic disenfranchisement called Abandoned Adopted Here.

“Spectacularly ordinary,” is how poet Paul Cookson describes his “very happy” childhood in Lancashire alongside three other siblings, all of them adopted. “None of us have ever looked into our birth parents,” he says. “We were very secure in our upbringing.” But he did accidentally come across his birth name: Christopher Goldsmith. “That was strange for a while. I’d never thought of myself as a different person.”

When Luis De Abreu was nine, he travelled from Madeira to join his mother in Jersey, where she’d been working for several years. Soon afterwards she died of cancer and De Abreu ended up, after several foster placements, living in the notorious Jersey children’s home Haut de la Garenne. He was badly bullied at school and his education “suffered terribly”, but he “soldiered on” and enrolled at Bird College aged 22 to study dance and musical theatre. He is now Bird’s principal and artistic director.

“It’s a mixture of stigma and admiration,” says Martin Figura of attitudes towards people in care. He spent his childhood moving between different carers after his mother was killed by his father in 1966. He wrote about the experience in his 2010 poetry collection Whistle, which was shortlisted for a Ted Hughes award and which Figura later turned into an Edinburgh show. He expected “a certain amount of difficulty” from the exposure but “it’s not made anything weird at all,” he says. “It’s been fine.”

Greg Bramble counts himself lucky that he and his brother Richard, also featured, had a stable experience with a foster family in Warwickshire, but leaving his birth family aged 10 was traumatic, and negotiating their new family life was often fraught. “You’re on your guard. It was a difficult situation,” he says. “You felt like you had to grow up too fast.”

“The issues around growing up in care don’t magically stop at 25, just because public policy stops,” says Jim Goddard, who went into care in Liverpool aged three. “They carry on, and people deal with them in various ways.” Goddard is the chair of the Care Leavers’ Association, which focuses on care leavers of all ages – it might help people access their care files, or deal with issues around social isolation. “The level of invisibility of the issues facing young people leaving care has not fundamentally altered in the past 20 years.”

“There’s still a very clear judgment passed when people hear you say, ‘I was in care,’” says Akiya Henry. Born in London, Henry was privately fostered at six months by a “wonderful couple” in Weston-super-Mare who encouraged her dreams of becoming an actor – she’s currently starring in Mad House in the West End. “In terms of the care system, everybody has such massively different experiences,” she says, “and the fact that sometimes we are all put into one bracket is, I think, a little bit unfair.”

Artist, puppet-maker and puppeteer for film and TV

“I decided quite early on that whatever happened to me, I wasn’t going to be a victim of it,” says Marcus Clarke, who lived in two national children’s homes in the early 60s, aged four to seven, while his mother was caring for his ailing father. (He later rejoined his mother after she remarried.) “I was mostly well looked after,” he says, “and learned to be happy in my own company.”

“I’ve become somebody to whom family and community is incredibly important,” says opera singer Jack Holton, who was born in Kent to a single mother with health issues and fostered at an early age. “One of the best things [foster care] has given me is the knowledge that it doesn’t need to be a totally typical family setup to work,” he says. “There’s all sorts of shapes of family that can work and your community can be whatever you choose it to be. It made me aware that families all look different – and that’s absolutely fine.”

Carl Parsons was adopted at five weeks. When he was six, his adoptive mother died and he was sent to live with relatives for 15 months, until his father remarried and he moved back home. “There’s a sort of stoicism,” he says, of how the experience shaped him. “Come what may, I may be knocked down, but I won’t be down for long.”

Artist and founder member of the darkroom e5process

Tina Rowe first encountered racism when, aged six, she moved with her white adoptive family from a small Oxfordshire village to Malvern in Worcestershire. The abuse she endured, none of which came from her own family, was “incomprehensible and frightening,” she says. It was only recently that one of her brothers acknowledged what she’d gone through and apologised for failing to confront it. “A lot of transracial adoptees talk about how racist their white families are, but actually, it’s racism that affects them too, and the way they see the world,” says Rowe. “It upset my brother when he realised what he hadn’t taken on board.”

In the 1990s Loo How, who was adopted at six weeks by “a very Christian white family” in Bristol, went on a journey to track down her biological parents. “I found my birth father very quickly, because he was an actor, Louis Mahoney, who was a big activist for Black, Asian and ethnic minority rights in the actors’ union Equity,” she says. “It was amazing to find him and realise where I get my activism from.”

“It’s one of the things that’s made me the happiest recently, the number of people who will happily associate themselves with their care experience,” says Jonny Hoyle. “It’s not a shameful thing any more.” Hoyle went into care as a young teenager and at 18 he set up a charity for care leavers called A National Voice: “We campaigned to stop children in care leaving with their belongings in bin bags.” Now he works for North Yorkshire county council “identifying and implementing ways that we can make life better for children in care”.

“Wherever I lived, my care experience included libraries and reading, and without them I wouldn’t be here,” says Rosie Canning, who was put into care in London at six weeks. “Books were a way to escape from the madness around me, be that foster care, family, or residential homes. Libraries were my hallowed space, and librarians were kind guardians who gave me orphan tales.” Now, as part of her PhD, Canning is writing her own novel, entitled Hiraeth, about a 16-year-old orphan leaving a children’s home in the mid-1970s.

Director of strategy and integration for Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust

“I’m hopeful that attitudes towards those in care are changing,” says Meera Mistry, who was in foster care in London for most of her teens. “The care-experienced movement is shaping some of the thinking – that people in care are talented and have so much potential. We can go on to do better if we’re just given the same life chances as other people. I am mightily proud of being care-experienced as it’s made me who I am today. Although it’s going to take time to shift the stigma and change the system, I believe it will happen.”

Best known for designing clothes for Diana, Princess of Wales, Bruce Oldfield was born in Durham and fostered at 18 months by a seamstress, Violet Masters, who taught him how to sew. From 13, he lived at a Barnardo’s care home in Ripon, North Yorkshire.

In the process of tracking down his birth parents, which is ongoing, Chris Fretwell learned that he was given up for adoption to cover up a family scandal: his parents were first cousins. “I just felt this overwhelming relief when I found out the truth,” he says, “because I was always told, they didn’t want you.” For Fretwell, writing and making films is a way of dealing with both his care experience and the racism he suffered growing up in Bognor Regis. “I’m getting to exorcise lots of demons.”

Now writing a memoir about her journey from care to Cambridge University, by day Kasmira Kincaid works as a fundraiser for Shelter. “I’ve had experiences with homelessness,” she says, “and it’s something that disproportionately affects people who are leaving foster care. It’s an incredibly common experience. I know so many care-experienced people who’ve had that further experience of being homeless, being a rough sleeper, living in hostels, sofa-surfing, all that kind of stuff.”

Pete Turner was adopted at five months and grew up in Bury in “a very liberal family that loved me,” he says. “They encouraged me in everything that I’ve wanted to do.” Which in Turner’s case meant becoming a musician – he’s a founder member of the rock band Elbow. “I know from reading the very brief information I have on my birth parents that my natural mother wanted me to have a better life than she could give me,” he says. Giving him up for adoption, he thinks, “was a massively selfless thing to do”.

“It was amazing to be seen,” says Olumide Popoola about some of the social workers who helped her through care in Germany. She lived with a foster family from 12 to 14 and then spent a couple of years in a children’s home. Both places recognised her writing talent and helped her get work published. Now Popoola is a novelist and an associate lecturer at Central Saint Martins in London. “I always feel these two years [at the children’s home] made it possible for me to be who I am today.”

Before joining digital arts platfrom WhyNow as creative director last year, Janet Lee worked for the BBC, where she was the editor of programmes including Imagine and The Culture Show and a producer on Desert Island Discs.

“I’ve never used it in a serious way, and I absolutely never will,” says Stewart Lee of mining his care experience for standup material – he was in care for the first year of his life before being adopted by a couple in Solihull. “Because it’s not just my story, it’s the story of the people that have been kind enough to reconnect with me and the people that were selfless enough to bring me up. I don’t feel like it’s for me to make a story out of their sacrifices and goodwill.”

Director of access and participation, Rada, and co-director of We Are Bridge

“It’s so important to celebrate the successes,” says Axa Hynes of the photoshoot at the Foundling Museum, “but because there were so many hurdles it can also feel uncomfortable, a distraction from the deep, systemic societal change that has to happen.” Hynes went into care aged 10, fostered by a family friend who had already been giving her family emotional and practical support. “By isolating and highlighting the success of care-experienced people it can become voyeuristic and soothes decision-makers into thinking that meritocracy is real. Instead of celebrating success ‘despite the odds’, we urgently need to improve the odds.”

“I came into care when I was 13, due to being homeless,” says Sanna Mahmood. Her care experience in West Yorkshire “was reasonably positive, partly because I was just happy to have a home. Someone gave me a fish-finger sandwich and I was like, I’ve made it.” Leaving care was harder: “The social housing that I got put into was not the best – there were needles all over the floor and blood on the wall – and the support wasn’t always the greatest.” Support for care leavers has since improved, Mahmood says, thanks to new policies from her local authority in Kirklees.

Jenny Bagchi spent time in foster care and unregulated settings as a teenager before experiencing an abrupt end to care at 16. Becoming a young parent motivated her to return to education as an adult. She is now employed by the NHS in Greater Manchester, leading a programme to create trauma responsive communities and organisations and to improve health outcomes and opportunities across the region. She is also a trustee of the charity Pure Insight, which supports young people to have a better care-leaving experience than she did herself.

“Being in foster care is probably the primary reason why I had a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder,” says Derek Owusu, whose award-winning debut novel, That Reminds Me, explores the after-effects of a childhood in care. “Though it was clear she loved and cared for us, my foster mum used to beat us with a cane. It didn’t feel like a traumatic experience at the time, but as I got older it dawned on me that an older, white, middle-class woman with seven black children in her house, beating them with a cane, was a bit strange.”

“I think of my life in two parts: before I traced my birth family and after,” says former Guardian journalist Hannah-Azieb Pool, who detailed the journey in her memoir My Fathers’ Daughter (republished this year). Pool was adopted from an Eritrean orphanage and lived in Sudan and Norway before coming to the UK aged six. Reconnecting with her birth family in Eritrea in her late 20s “allowed me to realise the multiplicities of who I am, to make connections around inter-country adoption, and the idea that you can belong in multiple places and with multiple families. It’s radically changed who I am.”

“Growing up, the moment someone found out I was care-experienced, they’d make negative assumptions,” says Lucy Reynolds, who had moved in and out of care eight times before being adopted aged seven. “I had teachers who put me in a box once they knew my background and said, ‘You’ll end up doing no good.’” Reynolds, who contributed to her mother Margaret’s 2021 book about adoption, The Wild Track, now studies ancient history and social anthropology at St Andrews and is involved in activist groups. “We need to prioritise the voices of people with lived experience of care,” she says.

An encounter with Sylvester Stallone in the Sinai desert, while working as an extra on Rambo III, prompted Mark Riddell to turn his turbulent care experience into a force for change. When Stallone heard Riddell’s tale of growing up in Aberdeen children’s homes in the early 80s, he urged him to share his story more widely. Riddell wrote a memoir called The Cornflake Kid. Now he’s a national adviser for England, “advising the government and local authorities how to have a better leaving care offer to the more than 80,000 kids that we’ve got in care”.

“It maybe shapes certain aspects of your character and your attitude to life,” says Tom Riordan of the experience of being in care. Riordan was in respite care several times during his first four years. “I was lucky to have a loving upbringing, but I find I’m never really happy with what I’ve done,” he says. “I’m always moving on to the next thing and thinking something’s going to go wrong.”

“This is a great opportunity to celebrate our achievements,” says Keith Saha of the Foundling Museum project. “A lot of care-experienced people will also measure success by how we’re feeling internally, how we manage our mental health and wellbeing, and not always what we’re achieving externally.” Moved into a children’s home aged six, Saha then went to live with adoptive parents in Merseyside the following year – a complex but positive experience for which he feels “lots of gratitude”. Now he works as a theatre-maker working with young and emerging artists, many of whom are also care-experienced.

Music producer/writer; founder of clothing labels Duffer of St George and Sharpeye; author; one of the two creators of the rare groove scene; photographer; activist

“My experience was a horror story, but it wasn’t so bad in other ways,” says Barrie Sharpe. “My mother was a manic depressive, so I was in and out of care. Visiting my mum in hospital, I’d see people screaming in straitjackets.” The upside of his experience, he says, was that he had “no fear” from a very young age, and he connects this to his career successes – DJing at London’s Wag Club in the 1980s, starting the clothing label Duffer of St George. “I was always falling uphill,” he says.

Being adopted “is definitely something that puts a mark on you,” says fashion and portrait photographer Philip Sinden. In junior school, he proudly announced that he was adopted and half-Pakistani. “I got racial abuse for a small amount of time,” he recalls. “Which is interesting, because I always saw myself as white.” The abuse was confusing, he says, “but I’m quite stubborn. It’s never really been something that had a lasting effect on me.”

“I was fostered till the age of one and then placed with my adoptive family,” says Annalisa Toccara. “Through my lived experience of being adopted, I co-founded a mental-health organisation called Adoptee Futures, which is led by adoptees and which centres adoptees. We look at reclaiming the adoption narrative and reframing the world’s view on adoption, and also helping adult adoptees heal from their trauma.”

“I was born in the era of forcible adoption – my mother was coerced into giving me up,” says Louise Wallwein. Her adoption broke down when she was nine and she moved through various children’s homes around Manchester until leaving care at 17 – “because I came out as a lesbian and it was a Catholic children’s home”. Wallwein later dramatised her search for her birth mother in the acclaimed one-woman show (later a book) Glue.

Writer and national campaigner for young people in care

Chris Wild has written two books about his experiences in care, Damaged and The State of It, and has spent the past decade campaigning to improve the care system. The motivation, he says, comes from “being 11 years old, losing my dad, going into a children’s home [Skircoat Lodge in Halifax], being really badly physically abused, ending up homeless, but then going back into the care sector and seeing that nothing had changed.”

“My care experience was both traumatic and enlightening,” says Johanan Walker, who went into care in east London after she had a baby at 12. “I was challenged with a lot of preconceived ideas and biases by the adults I was around, about whether I could be a mum and make it through against all odds.” Walker managed to hold on to her child and was later able to focus on education, “which saved me,” she says. Now she is a lived experience consultant and the co-founder of calling4gr8ness.org, supporting care-experienced young adults in the creative industries.

“I just felt I had to hide it,” says Sophie Willan, creator and star of Alma’s Not Normal, of her experience in care – she spent much of her childhood in foster care in Bolton. “It was actually seeing Lemn [Sissay] perform that helped me realise that you could talk about it. He really put it on the map and allowed it to be something that we could be proud of as an identity and talk about as a political thing. So it didn’t just have to be: this is your problem. It could be: this is everybody’s problem.”

“I’ve started to connect with my identity as an adopted person a lot more in the past couple of years,” says Luke Wright, who was adopted at five weeks. “If you’d asked me as a child, I’d be like, ‘Oh, I’m adopted but it’s not a thing.’” Now he acknowledges that “there is probably some degree of separation anxiety as a result of not being with my mother in those crucial first few weeks”. He is in two minds about searching for his birth parents. “You get to a point where you go, is my curiosity big enough to unsettle so much?”

“I became a journalist because I didn’t see my community represented in the newsroom,” says Sophia Alexandra Hall, an Oxford graduate who went into foster care as a teenager. “I wanted to tackle the sometimes subconscious, but overall still damaging stereotypes often perpetuated in the media, such as care-experienced people not ‘achieving’ or ‘succeeding’ in life due to their background. This photograph alone proves that with the right support and opportunities, those stereotypes are false.”

My own “success” happened in spite of my time in care, not because of it. I am not defined by my scars but by the incredible ability to heal. Healing can hurt too. Here are a few organisations for support and information: Become has been supporting and campaigning for children in care and young care leavers since 1985. The Care Leavers’ Association is a national user-led charity aimed at improving the lives of care leavers of all ages. The Fostering Network is the UK’s leading fostering charity; it champions fostering and seeks to create vital change. PAIN – Parents against Injustice is a voluntary organisation, run and funded by volunteers who provide help and support to families caught in the care system. Samaritans is a 24-hour service offering emotional support for anyone struggling to cope. One of the greatest signs of my own sense of independence when I left care was the day I could ask for help when I needed it.

Source: The Guardian

Powered by NewsAPI.org