The Fashion World Mobilized When AIDS Struck. Now It’s Coronavirus. - 9 minutes read

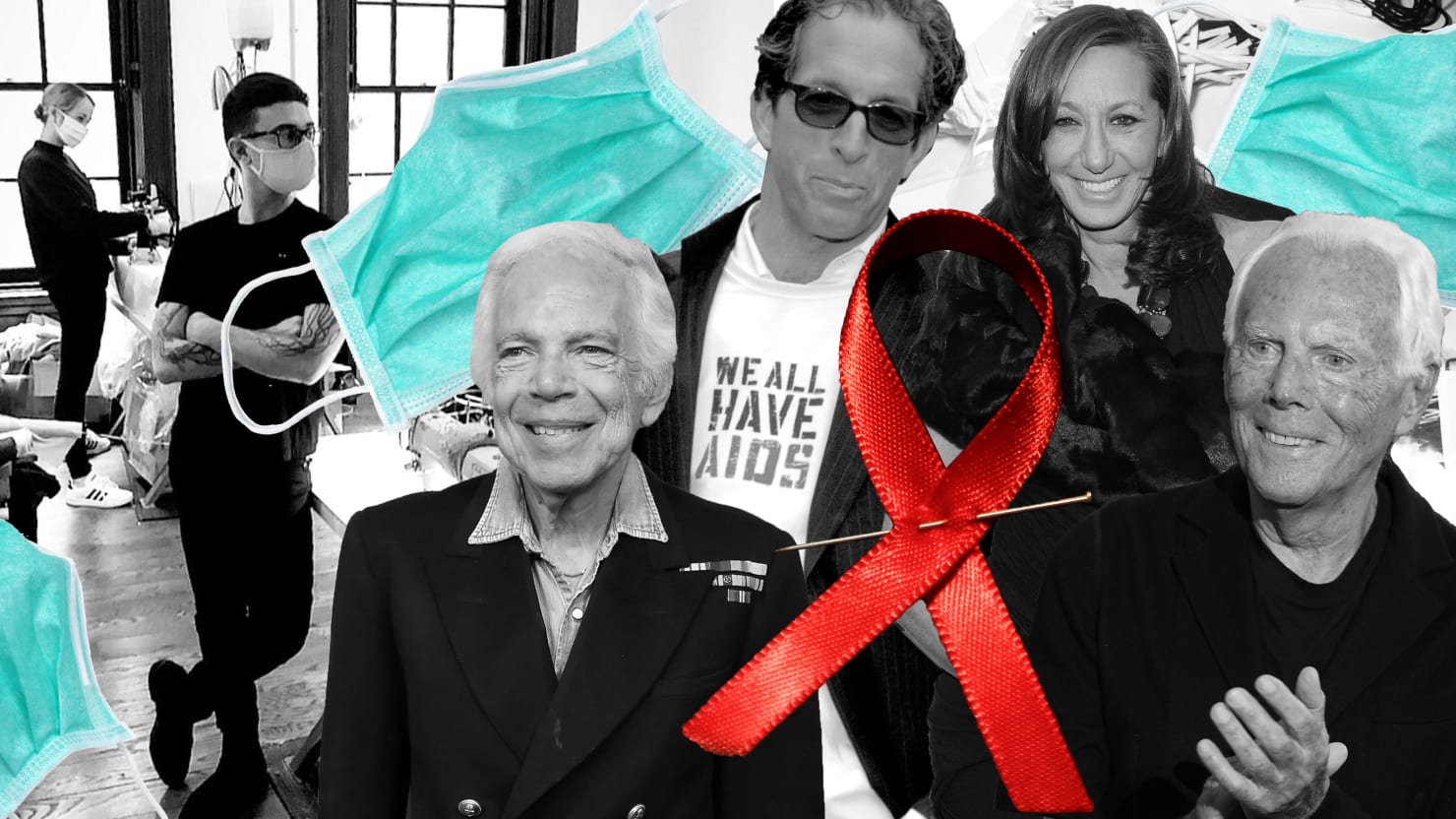

The coronavirus pandemic has gutted the fashion world, slashing jobs, closing department stores, and ravaging industry capitals like Milan, Paris, and New York. Events are canceled and trends hardly matter to those social distancing at home. It seems frivolous to care about fashion right now. But fashion still cares.

The coronavirus pandemic has gutted the fashion world, slashing jobs, closing department stores, and ravaging industry capitals like Milan, Paris, and New York. Events are canceled and trends hardly matter to those social distancing at home. It seems frivolous to care about fashion right now. But fashion still cares.In less urgent times, designers’ activism can feel gestural or hollow. Putting a runway model in a feminist slogan T-shirt does little for the general public. But when a true crisis hits, power players open their studios, supply chains, and (perhaps most importantly) wallets.

Anna Wintour, the editor-in-chief of Vogue and artistic director for Condé Nast, announced that her glossy, along with the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA), would open up a relief fund for those in the industry impacted by the virus.

A representative for Vogue sent The Daily Beast a statement from Wintour that read, “There are so many in need of help, especially as small businesses and workers across this country suffer devastating economic consequences. Many of those already affected are members of our fashion community, from designers to their employees to retail workers, up and down the economic scale. And all of us at Vogue—together with Tom Ford and the Council of Fashion Designers of America—are determined to help.”

The Ralph Lauren Corporate Foundation dedicated $10 million to fight the coronavirus and support colleagues hit by the pandemic. In Milan, the Armani Group donated 1.25 million euros to four different hospitals and the National Civil Protection Department. Gucci allocated more than 2 million euros.

Those employed at Prada’s Perugia, Italy, factory will produce medical overalls and masks. The same goes for the French luxury conglomerate LVMH, Kering, L’Oréal, and Hermès. Brands have retooled their perfume and makeup facilities to produce in-demand products like hand sanitizer.

On the west coast, smaller, popular brands like Reformation and American Apparel also offered up their resources to create masks. The New York designers Christian Siriano, Brandon Maxwell, Prabal Gurung, and Cynthia Rowley have also pledged their support to the city, and will make medical grade apparel.

The Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), may be closed as coronavirus ravages New York, but around the boroughs students, faculty, and alumni have mobilized to sew and deliver masks to health-care workers strapped for such essential utilities.

“The fashion industry does rise to the occasion,” Joanne Arbuckle, president for FIT’s Industry Partnerships and Collaborative Programs, told The Daily Beast. “People don’t often realize how socially conscious we are. When I started in this industry, everybody thought I was sitting by a window overlooking the Hudson River and sketching all day.”

Instead, these days Arbuckle leads grassroots efforts to produce masks for health-care workers. “Our faculty member who is leading the Manhattan, Queens, Brooklyn initiative has got a commitment from Supima Cotton to donate fabric,” she said. “So, one of the things I have to work on this weekend now is the logistics within the borough: How do we safely pick up the masks?”

It reminds Arbuckle of how FIT responded to Hurricane Sandy, where thousands of New Yorkers lost their homes and restoration efforts required an estimated $32.8 billion. Along with a group of interior design students, she went to Long Island to volunteer with construction companies and rebuild families’ homes.

“I was so impressed because the students were very sensitive to various socioeconomic levels and they made great design changes that were thoughtful in regard to budget,” Arbuckle said. “We’d source in IKEA for one client and Pottery Barn for another.”

Fashion’s ability to assemble may have been first tested during the AIDS crisis, which devastated the creative class and took the lives of designers like Willi Smith and Halston. Perry Ellis, then the president of the CFDA, also died of AIDS-related viral encephalitis at the age of 46, though he never publicly revealed his diagnosis.

“When I saw all my friends dying from the AIDS epidemic, I went to Perry Ellis with an idea to bring awareness to the issue,” the fashion designer Donna Karan told The Daily Beast. “He didn’t think it was appropriate to talk about it and said it was a private matter.”

Kenneth Cole, then a 31 year-old shoe designer, felt differently. “I didn’t feel at risk of the pervasive stigma [of HIV and AIDS], maybe because I wasn’t at risk,” he said. (Cole is straight and married to Maria Cuomo Cole, sister of the New York Governor.) “I saw an opportunity to do something that was meaningful at a time that others were reluctant to.”

In 1985, Cole set up a media campaign, shot by Annie Leibowitz, featuring famous models like Paulina Porizkova, Christie Brinkley, Kelly Emberg, and Beverly Johnson posing with children. Below the sober, black-and-white image read the copy, “For the future of our children, support the American Foundation for AIDS Research. We do.”

“I wanted to make a collective statement at the time about something few would,” Cole recalled. “How best to speak about HIV stigma, focused on gay men, then to get beautiful women and children? Bringing them all together was a very powerful moment because it showed me early on how people so badly want to be offered opportunities and platforms early on, and how you can take a meaningful stand on something that is bigger than what we do.”

After Ellis’ death in 1986, the CFDA enlisted Anna Wintour to plan Seventh on Sale, a gala and three-day shopping bonanza that ultimately raised $3 million for AIDS research. Kenneth Cole would become the chairman of amfAR in 2005, a position he would hold for 13 years, until he resigned after reports surfaced that he allegedly funneled charity proceeds to Harvey Weinstein’s investors.

“I stepped down—the whole board stepped down,” Cole said. “We all agreed to step down. It seemed like the right thing to do. I’d been on the board for almost 30 years. I built that board, and I built much of that organization. I felt it was the time to move on.”

Cole went on to say, “Harvey was an awful person. He devastated not just the women in his life, but the organizations he dealt with in business. I didn’t know that part of him. I read about it when everybody else did. But it was just an awful circumstance, and I think the system has played itself out. Hopefully we’ve learned something from it.”

“ The collective resources are definitely going to be so significantly compromised and diminished as a result of what we’re living through. I don’t know how we’ll come out at the end ”

As for the coronavirus, Cole has closed retail stores and pledged that 20 percent of net sales on his website will go to the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund. “I don’t know how we’re going to come through this today,” he said. “The collective resources are definitely going to be so significantly compromised and diminished as a result of what we’re living through. I don’t know how we’ll come out at the end.”

After his “Governor-in-Law” Andrew Cuomo put in a request for more masks and medical garments, Cole said his office began fielding “5 to 10” calls a day from people who had the resources and ability to produce the product.

“It’s wonderful,” he said. “That’s our industry. We inherently adapt to opportunities. Watching that happen now is very inspiring, how so many people were so willingly and enthusiastically prepared to address this need in the community.”

Coronavirus has made a hot spot out of New York, which still supports much of the fashion economy. That makes it impossible for designers to ignore.

“To have New York closed right now is not going to bode well for the immediate future of the industry,” Doris Domoszlai-Lantner, a fashion and textile historian, said. “Same with Milan and Paris. If you’re working within an industry that is affected by a crisis such as COVID-19, it makes sense for you to then contribute to alleviate the situation so you can get your industry back to normal as soon as possible.”

Fashion pulled off a successful rebound after 9/11 shook the city. Wintour and the CFDA created the original Fashion Fund in 2003, to aid emerging designers and ensure New York remained a style capital. Now, that same endowment will be repurposed for coronavirus causes.

Karan recalled 9/11, which occurred on the fourth day of New York Fashion Week. Her diffusion line DKNY was scheduled to have its show that day, and her eponymous high-end line was set to run the following Wednesday.

“[City] leaders asked me if they could use all the furniture that was for the show at the armory. It wasn’t even a question,” Karan wrote.

The Condé Nast headquarters—One World Trade Center—are also a symbolic nod to rebuilding after the attacks.

Past emergencies have required the famously social fashion world to come together and rally in star-studded fundraisers or glamorous auctions.

“ It’s uncomfortable for me to be forced to stay inside and not be out there helping the community on the front lines, so I am doing what I can by donating to those who can be ”

Bennah Serfaty, the senior director of communication for amfAR, recalled one 1999 Oscar dress auction spearheaded by Wintour and the late Natasha Richardson, which raised $1.5 million. Or the annual amfAR Gala at Cannes, which takes place during the film festival and garners $1 to $4 million a year.

But with coronavirus requiring social distancing, designers cannot throw their usual soiree or draw thousands together in protest. Those sewing masks in studios must do so in as small of a group as possible, six feet away. Suddenly, solidarity means loneliness.

“My heart goes out to everyone—patients, loved ones, nurses, doctors, and first responders,” Karan wrote. “It’s uncomfortable for me to be forced to stay inside and not be out there helping the community on the front lines, so I am doing what I can by donating to those who can be. We are coming together like we have in the past, and that’s what makes us powerful.”

Source: Thedailybeast.com

Powered by NewsAPI.org