Before Stonewall, Entrapment Was the Real Danger - 4 minutes read

Before Stonewall, Entrapment Was the Real Danger

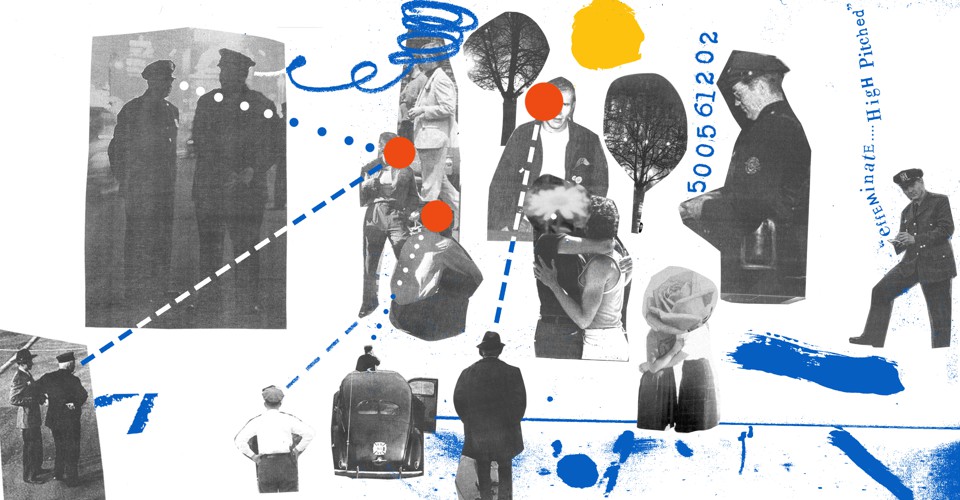

Before Stonewall, Entrapment Was the Real DangerEnding the use of entrapment was one of the signal victories of New York’s militant pre-Stonewall gay activists. Yet the courage, boldness, and success of those activists risk being forgotten in this summer’s sustained celebration of Stonewall as the event that launched the modern LGBTQ movement. At the same time, the movement’s extraordinary—if incomplete—success in changing American society in the 50 years since Stonewall makes it all too easy to forget the scale of anti-gay policing the movement faced. The tens of thousands of New Yorkers who were arrested for cruising in the 45 years before Stonewall have been even more thoroughly forgotten than the movement that fought on their behalf.

In the 1940s and 1950s, police surveillance was only the linchpin of a broader social system that punished people who were discovered to be gay. While the arrests themselves left some men in tears and others furious, almost every man taken into custody feared the possible extralegal consequences more than the legal process itself. Above all, these men feared that their families or their employers would learn they were gay if word of their arrest reached them, as sometimes happened when the police or court officials contacted them or, more rarely, a newspaper published the man’s name. Both families and employers had the power to impose more intimate and exacting punishment on people who refused to conform to heterosexual norms than the law did. The courts might punish a man with a fine or 30 days in jail. As shattering as this was to some men, it was nothing compared with the threat of losing a job, a career, or a family’s love and support.

Police and court records are full of scenes depicting the abject terror felt by men at the moment they realized how dire the consequences of an arrest could be. In the fall of 1948, a Dutch Jewish immigrant, who had lost his mother to the Nazis, desperately tried to outrun the police after he made the mistake of propositioning a plainclothes officer in a Grand Central Terminal men’s room. He was afraid, he later explained to a court official, that he would lose a precious new position as an import-export clerk trainee if he were sent to jail, and he pleaded guilty to avoid a trial that might bring the charge to his employer’s attention. He had reason to worry. In 1945, a copy editor who had worked at The New York Times for 17 years lost his job when the paper learned he had been arrested for homosexual solicitation. In 1950, a cabdriver who was his mother’s sole source of support lost his taxi license after being caught making out with a man in the back seat of his cab.

Aaron Payne did not suffer such dire consequences at the time of his arrests, because as a young black man without a job, he had little left to lose. But his arrests for “degeneracy” caught up with him at the very moment it seemed his life had turned a corner. His failure to receive a cabaret card derailed the professional career he had dreamed of before it even began.

Source: Theatlantic.com

Powered by NewsAPI.org

Keywords:

Before Stonewall • Entrapment • Entrapment • Activism • Stonewall riots • Homosexuality • Social status • Stonewall riots • LGBT • Stonewall riots • LGBT rights opposition • Before Stonewall • Surveillance • Social structure • Homosexuality • Family • Employment • Gay • Arrest • Police • Court • Man • Family • Employment • Power (social and political) • Intimate relationship • Punishment • Person • Heterosexuality • Norm (social) • Law • Court • Man • Fine (penalty) • Prison • Coercion • Employment • Family • History of the Jews in the Netherlands • Immigration • Nazism • Police • Undercover operation • Police officer • Grand Central Terminal • International trade • Trial • Employment • Reason • Copy editing • The New York Times • Employment • Homosexuality • Solicitation • Taxicab • Taxicab • The Man in the Back Seat • Aaron Payne • Devolution (biology) • New York City Cabaret Card •