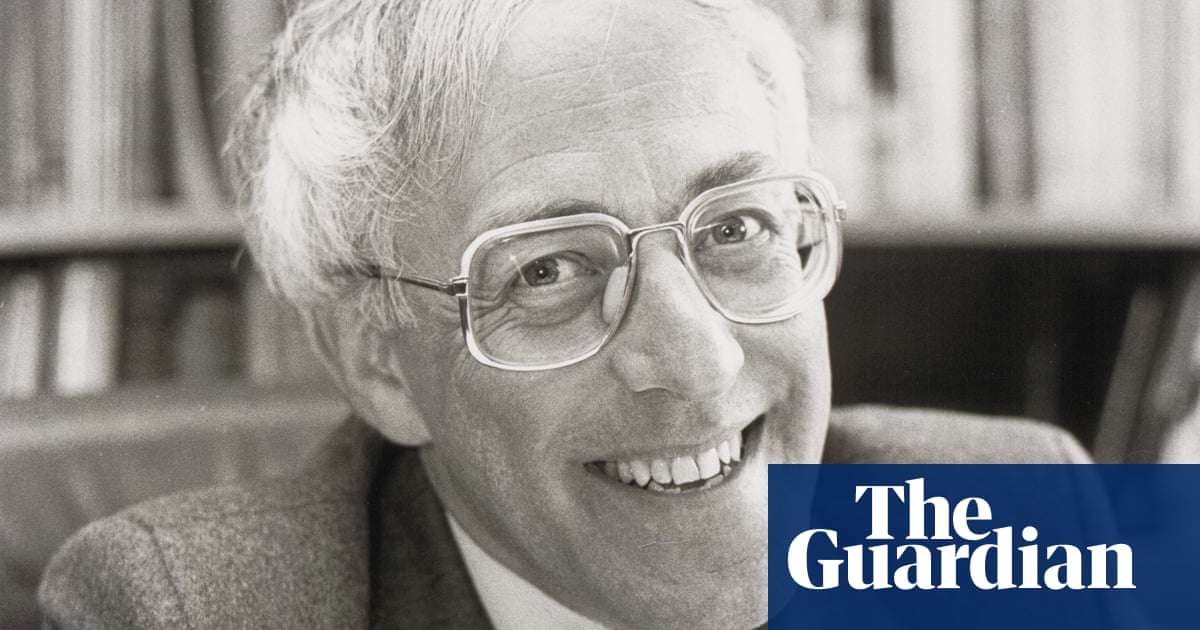

Anthony Smith obituary - 5 minutes read

Anthony Smith, who has died aged 83, was the brains behind the creation of Channel 4, which he envisaged as a new kind of publicly owned television channel for turning fresh ideas and minority views into programmes made by independent producers. At a time of just three channels, BBC1, BBC2 and ITV, he dedicated himself in the 1970s to media reform, and lobbied for an open broadcasting authority to run a vacant fourth channel, in a democratic opening up of the airwaves, unleashing “an imp in the mechanism”.

The Guardian acted as a facilitator, publishing two lengthy articles by Smith in 1972 and 1974 as he refined the concept. He then became director of the British Film Institute (1979-88), well positioned to influence the final decision. Although holding centre-left political views, he won support from Margaret Thatcher’s 1979 government, by meeting Keith Joseph, one of the prime minister’s most influential allies, and recasting the argument as a way of introducing competition and enterprise into broadcasting, while keeping public service dominant. Smith was a thinking person, combining unobtrusive sharpness with persistence: his personal charm and hospitality softened a serious intensity.

In 1987, he expected to succeed Jeremy Isaacs as chief executive of Channel 4, believing Richard Attenborough, the new chairman, had promised him the job. “There is only one reason I would take the job, darling. If I become chairman you will have to become chief executive when Jeremy goes,” went the reported exchange.

But when it came to the crunch, the board chose Michael Grade. Smith felt betrayed. “May God forgive them,” he said. I witnessed Attenborough delivering the news to Smith at the BFI, where he was launching the London film festival and his project, the Museum of the Moving Image, backed by Paul Getty. He crumpled. After he left the BFI, the museum eventually closed.

But he then enjoyed a remarkable consolation. In 1974 he had taken up a set of rooms in the Albany apartment complex on Piccadilly, opposite Fortnum & Mason, at the heart of the establishment. There he entertained stylishly: silver teapot, fruitcake, bone china cups and saucers. His open-house policy led by chance in 1988 to the “best bit” of his life, appointment as president of Magdalen College, one of Oxford’s oldest and wealthiest colleges.

A Financial Times foreign writer was a guest of Smith’s at the Albany, and his lengthy dinner with a fellow of Magdalen ended in the latter staying overnight on Smith’s sofa. Smith was suddenly on Magdalen’s radar. “I ran it,” he said with relish, “with a finger in every single pie.” The Grade I-listed buildings were cherished, but so was a new building, an auditorium where films were screened. In 1989 Magdalen launched the Oxford Science Park, now home to scores of businesses.

In 1999 he invited the Russian Yukos oil plutocrat Mikhail Khodorkovsky to a college dinner. At this point Khodorkovsky was seemingly espousing a new form of socially aware Russian capitalism: “He asked us to find a way to help very able young Russians undertake a degree at Oxford – a sort of Russian Rhodes scholarship – which the Rhodes Trust helped us with in the early years.” They were called Hill scholars, named after the office in Hill Street, off Piccadilly, administering the funds. But by 2003 Khodorkovsky had become a threat to Putin and was arrested and charged with fraud.

“As he was about to be arrested in Russia he sent a message asking if we would be willing to help establish a fund to cover the costs of Russian students in their own universities. He said there would be a large sum available,” said Smith. A donation of $500m arrived. Khodorkovsky was released from prison in 2013.

Smith meanwhile set up the Khodorkovsky Foundation, which he chaired, after checking with the Foreign Office and Charity Commission. This second initiative supports students through a network of 20 Russian universities. By 2020, 45,000 students and 150 Hill scholars had benefited. Its third duty is to support an orphanage school for 200 children near Moscow set up by Khodorkovsky’s parents. It also provides an English-language academic library.

Born Harrow on the Hill, northwest London, Anthony was the son of Esther and Henry Smith, a civil servant, and early in the second world war the family was evacuated to Rhyl, in north Wales. On their return to London, Anthony went to Harrow county school for boys, and from there to Brasenose College, Oxford, where he studied English. He joined the BBC in 1960 as a current affairs producer, editing 24 Hours, the influential daily current affairs programme launched in 1965, providing the template for Newsnight.

However, in 1971 he resigned and, as a fellow of St Antony’s College, Oxford, for the next five years developed his ideas on public service broadcasting in the belief that it was failing through being too middlebrow and out of touch. So he picked up his pen, turned to activism, mulled wider media reforms and outlined Channel 4. The most influential book of the 15 he authored was The Shadow in the Cave (1973), an examination of the relationship between the broadcaster, the audience and the state.

He submitted evidence to the Annan committee on broadcasting, whose eventual report in 1977 adopted the proposal for an Open Broadcasting Authority. He also contributed to the inconclusive Third Royal Commission on the Press (1974-77). Though in 1987 he was made a CBE, in Curran’s view he was “judged to be the enemy”.

Smith came to be highly critical of Channel 4, which he believed had lost its way after Grade’s arrival, though he welcomed those of its executives who consulted him. In 2005 he stepped down at Magdalen, and in his final years he enjoyed reading very long novels.

Source: The Guardian

Powered by NewsAPI.org