Leah Hunt-Hendrix and Astra Taylor on Solidarity, Change, and Our Interconnected World - 9 minutes read

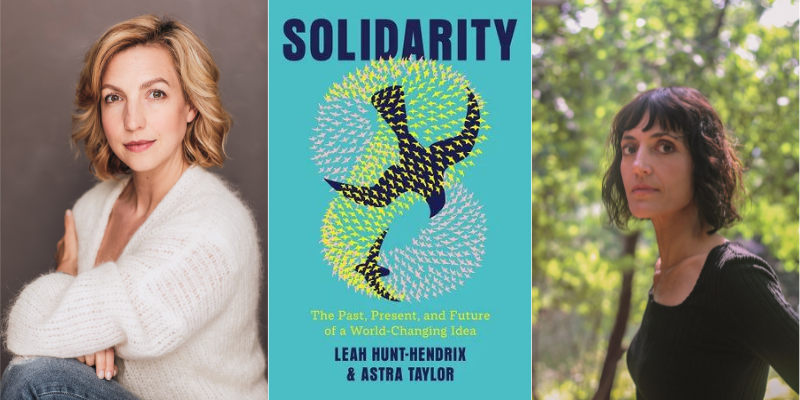

Authors and organizers Leah Hunt-Hendrix and Astra Taylor join co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to talk about the concept of solidarity, its reliance on relationship-building, and how it has been expressed in political movements, from recent pro-Palestine activism in the U.S. to the Polish organization Solidarność, a trade union founded in the 1980s. Hunt-Hendrix and Taylor, authors of a new book called Solidarity: The Past, Present, and Future of a World-Changing Idea, also reflect on how solidarity relates to their own work. Hunt-Hendrix recalls her dissertation on solidarity, and Taylor discusses her role as a founder of the Debt Collective, a union of debtors. They interrogate two kinds of solidarity, transformative and reactionary, as they exist across the political spectrum, and read from Solidarity.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf and Llewyn Crum.

*

From the episode:

V.V. Ganeshananthan: A lot of the people who are protesting right now are citing solidarity, not just with civilians in Gaza, but also with each other as a motivation for their activism. People have been comparing these protests to the ’68 campus protests against the Vietnam War, which appear in a novel we talked about a couple of weeks ago, There’s Going To Be Trouble by Jen Silverman. I’m curious how you all think these Gaza solidarity protests—and most of these encampments are called Gaza solidarity encampments—how these relate to the idea of solidarity as you present it in your book, how they compare to ’68, how they compare to other historical examples that you cite? And Astra, maybe you want to start?

Astra Taylor: Yeah, there’s a lot there. I mean, I’m just blown away by these solidarity encampments on campuses and the fact that they’re being met with this outrageous repression. I mean, these are peaceful demonstrations. And university administrators are calling in the police to clear them extremely violently. You mentioned Emory University, which is in Atlanta. There are videos circulating as we speak of professors being taken into custody, often with quick, brutal force. And so what we’re seeing there is faculty standing up for students, there have been numerous campuses where faculty have formed a ring around their students and become a kind of shield in solidarity with the students. Leah and I have been actually wondering what can we even add to this, you know? People are actually doing it right now, building solidarity in this amazing way.

I think there are some lessons from the ’60s. And one lesson I took… I actually wrote my master’s thesis on the protest movements of the ’60s and the student movement. And one is that students alone cannot be the agent of historical change. And youth movements are really important. But they don’t—and this is actually a lesson from the solidarity movement in Poland as well, which is a movement we talk about, that people often refer to—students don’t have a lot of economic power, right? This is why the labor movement is really important. Labor can shut down the means of production. One lesson is like, we have to be in solidarity with students, “we” being the whole of society, because they alone can’t fix things. So there’s always this cliche of, “The children of the future, the young folks are gonna save us.” And I think one lesson the ’60s teaches us is: We shouldn’t fetishize youth, [and] that actually what we need to do is step up as well. And I say that now that I’m an old person. So that’s one thing that’s been on my mind. So I think this is actually a real moment where people need to step up and support them. So I’ve been very happy to see the faculty do that.

And so solidarity has many dimensions. But one thing Leah and I emphasize is that it’s not pity or altruism. It’s not charity. Solidarity requires recognizing your self interest. And that can be a really powerful thing. Solidarity is again, relational, it speaks to our interdependence. So what does it mean to say “Emory is everywhere?” What does it mean to really say, “Actually, what’s going on on that campus is part of my life, too.” And to kind of recognize the stakes. So what are the stakes for me? One is, I don’t like the fact there’s a genocide, that’s abhorrent to me. But the other thing is, this war is demolishing international law and the human rights regime, as imperfect as it is. I have a stake in that. I have a stake in that as a citizen of the world.

Students are also being attacked as part of a bigger proxy war attack on higher education in general, which I see as an attack on a core democratic institution. And so, what I’m just saying is that we need to recognize that these fights are not just about something far away, that they actually really do speak to our own lives and our futures, and that should help motivate us to really get engaged with them and to see that there are stakes. I just think it is an incredible moment of solidarity. And people are showing incredible courage in the face of real crackdowns against, and real criminalization of, solidarity. I mean, these students are facing expulsion, suspension, really potentially devastating consequences for their lives. And so solidarity demands that we step up and try to support them in meaningful ways.

Whitney Terrell: Wouldn’t, in the case of Gaza, the most helpful kind of solidarity be solidarity between Palestinians and Israelis who don’t agree with their governments’ policies, right, forming connections in that way? Is that part of the idea of solidarity?

Leah Hunt-Hendrix: Absolutely. And that’s definitely happening; there are a number of groups building solidarity between Palestinians and Israelis. A Land For All is one that Astra and I have both engaged with. Standing Together. There are so many and there have been many at work for decades. And you know, here in the States, we’re seeing that many of the students and many of the people who have been involved in these protests at large are Jewish, and even feel a connection to Israel, but are just against the war. And so, absolutely, I think it’s been just an amazing outpouring of that kind of Jewish, Jewish Muslim and Israeli Palestinian solidarity.

WT: I saw on Instagram, there’s a big influencer named Zibby Owens, who has been—I don’t know if you guys know her, but she’s in my feed a lot. Do you know? Yeah, so I was watching this video of hers, it was posted a little while ago, but she was explaining that the owner of a coffee shop or something has fired all of his employees for supporting Palestine. And so she’s now so excited that a group of Jewish and Israel supporters have lined up to buy coffee. And she views this as an instance of solidarity. She’s interviewing everyone in line and saying, “I really appreciate your support.” That’s not the kind of solidarity that I was hoping for. What would that be called?

AT: Well, that’s reactionary solidarity, right? That’s precisely the solidarity that seeks to shrink the circle of inclusion. And to name the other—

WT: “It’s good that you fired these people and didn’t listen to them and have no concern about what they’re saying.” Okay.

AT: Yeah, and that’s—again, reactionary solidarity, group cohesion in this negative sense—is a real thing. And it’s really dangerous. One thing we see from the Netanyahu government, too, is that that circle keeps getting smaller and smaller. So people who speak out against the genocide are not real Jews, right. And you’re never, sort of, pure enough. Or you never meet that standard enough. And it becomes a means of just casting people out. And in its most dangerous formation, reactionary solidarity says, “Okay, you’re not in so we’re going to annihilate you.” It can become genocidal. We can’t put on rose-colored glasses about human relationships. And that’s why it’s important to name transformative solidarity. And it’s not just like, one is good and nice and one is mean. So I think one misdirects us. What reactionary solidarity says is that that group—in this case, Palestinians—are the problem.

LHH: And you’re only safe if they are annihilated?

WT: And we can have reactionary solidarity on the left as well, there’s been plenty of examples of that.

AT: Yeah. And we actually, in the book, discuss some tendencies on the left that we take issue with. So where people become rigid and purist as well on the left, and end up shrinking the circle instead of trying to build bridges and build a majoritarian movement. So absolutely, we can see this tendency to turn inward in various communities, which is why we counsel a kind of solidarity, we say that the core component of transformative solidarity is hospitality, which is like trying to bring people in. Curiosity, trying to see why people will think the way they do. And to just remind ourselves of the dangers of that exclusionary, reactionary approach.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Madelyn Valento.

*

Leah Hunt-Hendrix and Astra Taylor

Solidarity: The Past, Present, and Future of a World-Changing Idea by Leah Hunt-Hendrix and Astra Taylor • Capitalism Cries: Class Struggles in South Africa and the World by Leah Hunt-Hendrix, William K. Carroll, Vishwas Satgar • The Age of Insecurity: Coming Together as Things Fall Apart by Astra Taylor

Others:

The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together by Heather McGhee • There’s Going To Be Trouble by Jen Silverman • The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, a Study in Religious Sociology by Emile Durkheim • Fiction/Non/Fiction: Season 7, Episode 29, “Jen Silverman on Generational Divides in American Politics” • “Zibby Owens withdraws sponsorship for the National Book Awards over its ‘pro-Palestinian agenda,’” by Dan Sheehan | LitHub • Solidarność • “The Triumph and Tragedy of Poland’s Solidarity Movement,” by David Ost | Jacobin | August 24, 2020 • A Land for All • Standing Together • Emory is Everywhere (via Twitter)

Source: Lithub.com

Powered by NewsAPI.org