Amazon at 25: The magic that changed everything - 14 minutes read

Amazon at 25: The magic that changed everything

Amazon at 25: The magic that changed everythingThe idea from the start was magic.

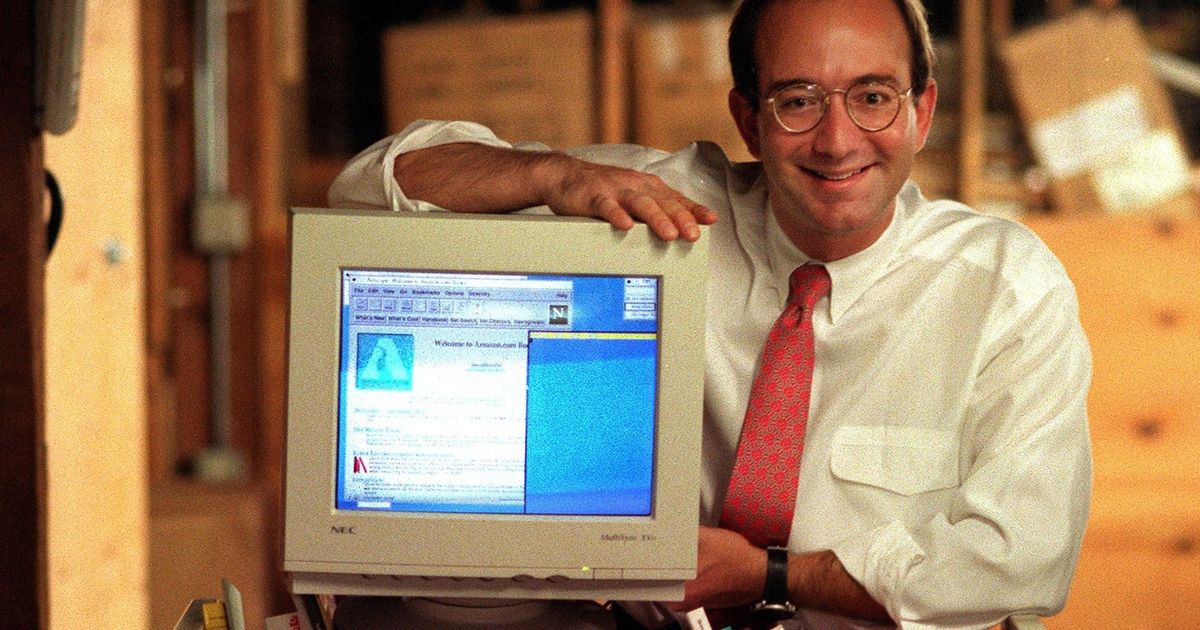

Jeff Bezos filed the paperwork July 5, 1994, to create Cadabra Inc. — as in abracadabra, presto change-o.

In the quarter century since, his erstwhile electronic bookstore changed nearly everything about publishing, retail, computing and how to run a company. It has ever-growing fleets of airplanes, drones, trucks and robots; it is moving deeper into entertainment, health care, groceries, advertising, home security, artificial intelligence and more.

In the process, it has transformed this city, recruiting tens of thousands of skilled workers, minting another round of tech millionaires and stamping new towers on the skyline. At the foot of the “Day 1” building, where Bezos has his office, is a trio of enormous glass spheres, just down the street from Seattle’s other symbol of futuristic ambition and industry, the Space Needle.

The wealth generated by the Amazon juggernaut fuels Bezos’ childhood dreams of rockets and moon landings, and enabled him to buy The Washington Post.

If you’ve fully bought in to Amazon’s system of systems, you can speak your wish aloud to a microphone installed in your home, triggering a chain of events across a sprawling mechanism of computers, machines and people that ends at your door as little as an hour later with the wish fulfilled.

It is tantamount to magic, the near perfection of consumer capitalism that has made Bezos the richest person on Earth. The name Cadabra was a reflection of this ambition. “He had that vision from the beginning,” said Tom Alberg, who invested in the company earlier than almost anyone and served as a board member for 23 years.

But Cadabra sounded too much like “cadaver,” so in November 1994, Bezos changed it to Amazon.com Inc. The reference to the lengthy South American river was meant to signal a vast selection, and the choice of a name beginning with “a” put the site high on early alphabetical web listings.

Amazon embarks on its second quarter century in business more visible and powerful than ever in Seattle, the nation and across the globe, but it also faces a mounting array of challenges and criticisms. Amazon was worth more than $937.5 billion at its closing price on Friday, making it the world’s second-most valuable public company by market capitalization, behind Microsoft. Amazon employed about 647,500 people at the end of 2018.

Amazon considers its anniversary to be the date it opened to the online public, July 16, 1995, a little more than a year after it incorporated in Washington. The first story on the company appeared in The Seattle Times two months later informing readers: “There’s a big, new bookstore in town, and there’s a catch — you won’t find it on any Seattle street map. So if you want to wander down its aisles and peruse the selection, you’ll have to hook up to the Internet.”

Amazon marks its birthday with an invented shopping holiday that many of its competitors now feel compelled to “celebrate” with sales of their own, illustrating its sway over the retail industry. But its impact stretches far beyond retail.

The dominant 20th century system of industrial mass production and consumption is sometimes referred to as Fordism, after Henry Ford and the Ford Motor Company.

Margaret O’Mara, a University of Washington historian, wonders if Amazon may be as influential. “Decades in the future,” she said, “are we going to be talking about Bezosism?”

O’Mara sees an apt comparison in another era-defining business: the railroads of the late 19th century, which like Bezos’ company, rewrote the rules of space and time, compressing the gap between desire for a thing and possession of it.

The railroads at the height of their powers capitalized on technological advances and created infrastructure that drove broader societal and economic changes, but also attracted regulatory scrutiny, said O’Mara, whose forthcoming book “The Code” charts the rise of the modern technology titans, including Amazon.

“A lot of the political conversation a hundred-and-some years ago was around what role should the federal government play in regulating or creating a balance to these incredibly powerful companies,” she said.

Amazon, along with Google’s parent company and Facebook, have lately become a hot topic in academic antitrust circles, and the federal government is increasing its scrutiny of the companies, according to reports earlier this month.

“We’re at a very consequential moment in American history generally, but American business history in particular,” O’Mara said.

The Amazon origin story is well known. While working at a Wall Street hedge fund, Bezos encountered a statistic on the rapid growth of internet usage — 2,300% a year. That first Seattle Times story from 1995 estimated that between 2 million and 13.5 million people were using the World Wide Web. Last year, there were an estimated 3.8 billion.

“I picked books as the first, best product to sell online after making a list of like 20 different products that you might be able to sell,” the 33-year-old Bezos said in a 1997 interview taped outside a conference in Seattle for library professionals. With more than 3 million books in print, “you can literally build a store online that couldn’t exist any other way.”

He added, “This is the Kitty Hawk stage of electronic commerce. We’re moving forward in so many different areas.”

Early employees traded an anecdote passed down from Bezos called the “Kayaking Thing,” which was “the corporate equivalent of holy writ,” as employee No. 55, James Marcus, wrote in “Amazonia,” his 2004 memoir of early life inside the company. It was explained to him this way: Someone who visits the site interested in kayaking can of course find a book on the subject. “But Jeff wants to offer that same visitor the opportunity to buy a spare paddle, or a waterproof kayaking jacket.”

Those personalized recommendations were an early example of the fundamental role of data and technology in Amazon’s retail model. Amazon’s deep well of personalized shopping and product data, collected over the years, give it the raw material for algorithms that automate tasks at its now enormous scale.

Jenny Freshwater, an Amazon director of forecasting and capacity planning, said at a company conference last month that her team uses artificial intelligence to predict demand for some 400 million different items, including something obscure like a Nicholas Cage sequin pillow. An Amazon neural network can sift through the demand histories of thousands of similar products to forecast the likelihood that someone will order that pillow. The company can probably get it to the customer’s doorstep within two days, Freshwater said.

Today, Amazon likes to emphasize how others make money on its many properties.

Dedicated Amazon pages explain how to sell branded items, handmade goods, services and apps; deliver packages for Amazon for an afternoon, or as a new small business; advertise and influence on the company’s behalf; self-publish writing or videos, or stream video-game playing to an audience.

The company touts the way it has enabled small businesses across the country and around the world to reach customers, competing directly with merchandise Amazon buys itself and sells to customers. In the latest version of the annual letter Bezos writes to shareholders, he said 58% of gross merchandise sales through Amazon came from third-party sellers.

Third-party sellers pay Amazon a variety of fees depending on the product category to connect to customers over its website and deliver the purchases using its warehousing and logistics systems, generating more profit for Amazon. But this opening of its platform has also brought frustration for both sellers and customers who encounter fake reviews, counterfeit products and a sometimes inscrutable bureaucracy — things Amazon says it is working to improve.

As Amazon’s retail business grew larger and more complex, software engineers built a new standardized, web-based system to manage it. They suggested renting excess capacity on this computing platform to other businesses, and Amazon Web Services (AWS) was formally launched in 2006.

Despite its size, Amazon, as a retailer, was not a wildly profitable company. It survived early skepticism, the 2000 dot-com bust (albeit with a major round of layoffs) and didn’t turn an annual profit until 2003. For many years thereafter its profit margins were slim or nonexistent. Bezos has always taken a long-term approach to building the company, and often chose to invest cash into growing new business lines. For the most part, shareholders and analysts proved patient.

AWS turned out to be the most profitable part of Amazon, gushing cash the company has continued to reinvest in things like its $13.7 billion acquisition of Whole Foods Market in 2017.

“AWS is extraordinary, and it makes Amazon about much more than Amazon,” O’Mara said.

With the advent of cloud computing, the Seattle area became home to an information technology revolution for a third time, following Microsoft’s dominance of the desktop computing era and mobile communications pioneers like McCaw Cellular.

Microsoft, Google and Apple have all followed Amazon into the cloud, the latter two with major engineering offices opening within shouting distance of the dense South Lake Union campus where Amazon began consolidating its headquarters in 2010.

Alberg, co-founder of Seattle investment firm Madrona Venture Group, said Seattle was lucky that Bezos chose the city over Portland or the Bay Area to launch his startup.

Bezos needed software engineers, and there were lots of them working at Microsoft — the definition of success to which dot-com startups aspired in the mid-1990s. He also recognized the expertise in the University of Washington’s computer science department, Alberg said.

“He was very focused on hiring top-flight people from the beginning,” he said.

And there was a tax component: By locating the company outside California, Bezos could sell into that large market without collecting sales tax from customers there, giving Amazon a price advantage over its physical bookstore competitors.

Amazon has long been an expert at minimizing taxes, suing New York in 2008 over a law requiring online retailers to collect sales taxes on shipments to state residents. More recently, state and local governments across the continent offered Amazon billions of dollars in tax breaks and incentives in a bid to attract the company’s second headquarters, and tens of thousands of high-paying jobs.

Amazon’s local growth — it now has more than 45,000 employees in Seattle and a growing presence in Bellevue — has contributed to a population and wealth boom, and the attendant struggles that come with it: soaring housing prices, worsening traffic, a homelessness crisis. The company is engaged more deeply in local politics than ever and has stepped up its philanthropy on several fronts, including providing space for a shelter for unhoused women and families in one of its Seattle buildings set to open next year.

Despite recent antagonism with city hall, Alberg dismisses any suggestion that Amazon has plans to leave Seattle, despite its decision to establish an “HQ2” outside Washington, D.C., and expand across Lake Washington.

“Seattle is going to continue to be highly important to them,” he said. “It is HQ1.”

Adam Selipsky, who left AWS in 2016 after 11 years to head Tableau Software (just sold to Salesforce in a $15.7 billion deal), said Amazon has helped brand Seattle “as a high-tech center of the country, and in fact, the world.”

“When I grew up here, if people had heard of Seattle, it was for Boeing,” Selipsky said from his glass-walled office, which looks directly across Lake Union to the downtown skyline, utterly transformed in the last decade by Amazon’s growth.

That shift from “Jet City” to “Cloud City” has been good for business, for recruiting employees, and “for the morale of the Pacific Northwest, and civic pride,” Selipsky said.

Meanwhile, at least on the internet, Amazon the company has surpassed the geographic feature from which it took its name. Search results for the word “Amazon” go on for pages before offering a reference to the river or jungle. The company just won a seven-year battle to control the “. amazon” domain name, over the objections of South American governments in the Amazon basin.

The commerce giant, in one of its few ostentatious displays, opened the Spheres in 2018. This unique workspace — filled with hundreds of plant species from cloud forests around the world — has quickly become a recognizable local landmark. Earlier this month, a corpse flower inside bloomed, producing its distinctive smell: like a cadaver, not to be confused with Cadabra.

Source: Seattletimes.com

Powered by NewsAPI.org

Keywords:

Amazon.com • Jeff Bezos • Abracadabra • The Fairly OddParents (season 5) • Retail • Computer • Corporation • Unmanned aerial vehicle • Robotics • Entertainment • Health care • Advertising • Artificial intelligence • Office • Glass • Seattle • Space Needle • Amazon.com • Semi-trailer truck • Jeff Bezos • The Washington Post • Amazon.com • System of systems • Microphone • Machine • Machine • Consumer capitalism • Tom Alberg • Cadaver • Amazon.com • American River • Amazon.com • Seattle • Amazon.com • 1,000,000,000 • Public company • Market capitalization • Microsoft • Amazon.com • Amazon.com • The Seattle Times • Internet • Amazon.com • Holiday • Competition • Sales • Retail • Industry • Mass production • Consumption (economics) • Fordism • Henry Ford • Ford Motor Company • University of Washington • History • Amazon.com • Future • Era • Law • Motivation • Object (philosophy) • Ownership • Power (social and political) • Technology • Infrastructure • Society • Economy • Amazon.com • Federation • Amazon.com • Google • Facebook • Hot Topic • Competition law • American business history • Amazon.com • Origin story • Wall Street • Hedge fund • Jeff Bezos • Internet access • The Seattle Times • World Wide Web • Seattle • Kitty Hawk, North Carolina • E-commerce • Kayaking • Employment • James Marcus (American actor) • Amazon rainforest • Kayaking • Kayaking • Technology • Amazon.com • Retail • Amazon.com • Personalization • Online shopping • Product (business) • Data • Raw material • Algorithm • Automation • Amazon.com • Forecasting • Capacity planning • Company • Artificial intelligence • Carlo H. Séquin • Amazon.com • Artificial neural network • Amazon.com • Amazon.com • Mobile app • Amazon.com • Small business • Advertising • Self-publishing • Streaming media • Video game • Audience • Product (business) • Amazon.com • Sales • Customer • Shareholder • Product (business) • Sales • Amazon.com • Supply and demand • Amazon.com • Customer • Warehouse • Logistics • Profit (economics) • Amazon.com • Supply and demand • Customer • Copyright infringement • Bureaucracy • Amazon.com • Amazon.com • Complexity • Software engineering • Technical standard • Web application • System • Computing platform • Business • Amazon Web Services • Amazon Web Services • Retail • Profit (economics) • Company • Dot-com bubble • Company • Cash • Business • Shareholder • Amazon Web Services • Profit (economics) • Amazon.com • Cash • Company • Takeover • Whole Foods Market • Amazon Web Services • Amazon.com • Amazon.com • Cloud computing • Seattle • Information technology • Microsoft • Desktop computer • Mobile telephony • Innovation • AT&T Wireless Services • Microsoft • Google • Apple Inc. • Amazon.com • Cloud computing • Engineering • South Lake Union, Seattle • Amazon.com • Tom Alberg • Seattle • Madrona Venture Group • Seattle • Portland, Oregon • San Francisco Bay Area • Startup company • Software engineering • Microsoft • Dot-com company • Startup company • University of Washington • Computer science • Carl Alberg • Company • California • Market (economics) • Sales tax • Customer • Amazon.com • Price • Competition • Amazon.com • Law • Sales tax • State court (United States) • Amazon.com • Company • Employment • Amazon.com • Economic growth • Employment • Seattle • Bellevue, Washington • Wealth • Business cycle • Homelessness • Financial crisis of 2007–2008 • Company • Local government • Seattle • Tom Alberg • Amazon.com • Seattle • Hex Hector • Washington, D.C. • Lake Washington • Seattle • Amazon Web Services • Tableau Software • Salesforce.com • Amazon.com • Seattle • High tech • Seattle • Boeing • Lake Union • Downtown Seattle • Amazon.com • Bespin • Value (ethics) • Business • Employment • Morale • Pacific Northwest • Citizenship • Internet • Web search engine • Amazon Go • Domain name • Amazon basin • Carrion flower • Cadaver •